When we think of writing systems we likely think of an Alphabetic writing system, where each symbol (letter) in the alphabet represents a basic sound unit, such as a consonant or a vowel.

Those who first came to the shores of Australia during colonisation likely held a similar idea of written language. As such, Aboriginal peoples were quickly dismissed as lacking a written language.

But this view is wrong.

Aboriginal message sticks, traditional tools of communication, offer a glimpse into a sophisticated and unique form of communication.

A written and oral language

Aboriginal message sticks are hand-carved wooden objects traditionally used to send messages across long distances. While there is evidence of widespread use of message sticks across Australia, the current database is still mapping the different regions in which they are used and their messages deciphered.

Message sticks often feature engravings or painted symbols, lines, dots and shapes carefully crafted to convey specific meanings.

They aren’t standalone texts, like books or letters. Instead, they are complemented by oral messages delivered by an appointed messenger who, in some instances, would be painted in ochre and dressed according to the message being delivered.

This ensured the stick’s symbols were interpreted correctly by the recipient.

The messenger’s task was to deliver the stick and speak the words that gave the symbols life and meaning. A message stick might feature simple symbols representing the date, location and purpose of an event. While the symbols carry visual meaning, the oral storytelling supplies context.

Imagine you had to send a crucial message, perhaps an invitation to a wedding or news of a tragedy. When composing your message you carefully select the right words so that your intended meaning is interpreted correctly.

Similarly, the symbols carved by the sender into the message stick and the accompanying oral message provide the same function.

A long history of writing

Pictographic writing, a system where ideas, objects or sounds are represented through visual symbols, is a foundational stage in the evolution of writing.

Unlike writing systems that use letters to represent sounds, pictographic systems use pictures that directly resemble what they represent, while some systems mix symbols for whole words or parts of words.

Hieroglyphs from ancient Egypt originally started as a pictographic writing system before transitioning into a logosyllabic system.

An example of early Egyptian pictographic writing can be seen in the Narmer Palette, a ceremonial artefact that depicts King Narmer’s unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Its carvings include early hieroglyphic symbols that are primarily pictorial, representing objects like animals, tools, and body parts.

Likewise, writing from Aztecs from Mesoamerica also started as a pictographic system. The Aztecs used pictographs to record events, genealogies and religious rituals.

The Codex Borbonicus is a prominent example, created by Aztec priests before the Spanish conquest, conveying religious, calendrical and ritualistic information.

Like the Aztec and early Egyptian pictographs, the symbols on message sticks hold complex and culturally significant information.

These symbols vary depending on the region and the purpose of the message. Common symbols include straight lines, dots, concentric circles, cross hatching or geometric patterns, animal tracks and wavy lines.

The meaning of these symbols are dependent on the region they are from and the context supplied with the message.

For too long, pictographic systems have been dismissed as inferior or proto-writing within Eurocentric frameworks.

This perspective has contributed to the marginalisation of Indigenous knowledge systems. The claim that Aboriginal peoples lacked a written language is a misrepresentation borne of colonial agendas, designed to dehumanise and delegitimise Aboriginal cultural sophistication.

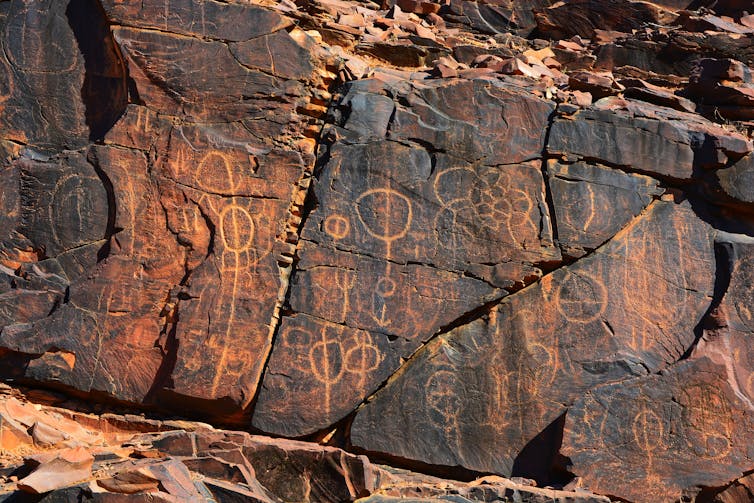

Message sticks and other forms of Aboriginal graphic expressions, such as rock art and carvings (petroglyphs) challenge this narrative.

These artefacts demonstrate that Aboriginal peoples developed complex systems of visual communication intertwined with oral traditions.

Recognising Aboriginal message sticks within the succession of pictographic communication legitimises their status as a form of written communication and honours their role in the diverse spectrum of human intellectual achievements.

Understanding the breadth of writing

The devaluation of Aboriginal graphic writing systems reflects a broader colonial bias that equates written language exclusively with alphabetic systems.

By acknowledging the legitimacy of pictographic writing, we validate the cultural practices of Aboriginal peoples and broaden our understanding of what it means to write.

Writing is not merely a mechanical act of inscribing symbols on a surface. It is a medium through which humans convey meaning, preserve knowledge and create connections across time and space.

Message sticks are compelling evidence of Aboriginal systems of knowledge and communication.

These artefacts demand a reevaluation of how we define and value writing. They also challenge us to confront the colonial legacies that have marginalised non-alphabetic systems of communication.

Writing is not a singular invention. It is a diverse, multifaceted human endeavour. Like the hieroglyphs of Egypt and the Aztec glyphs, message sticks are powerful symbols of the intellectual and creative capacities of their creators.

Athena Lee does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.