In the first quarter of his first game as a New York Jet, quarterback Aaron Rodgers dropped back to pass. Buffalo Bills defensive end Leonard Floyd blew past the offensive line and wrapped up Rodgers, dragging him awkwardly to the ground. Rodgers got up, before falling back to the turf, grimacing in pain.

Just like that, the Jets lost their biggest offseason acquisition to a season-ending Achilles tendon tear.

Blame quickly circulated. To some football players, it wasn’t Rodgers’ age – the quarterback will turn 40 in December 2023 – nor was it simple bad luck that caused the injury.

It was the artificial turf at MetLife Stadium, where the Jets and New York Giants play their home games.

Two days after the injury, the NFL Players Association called on the league to convert all playing fields to natural grass. It joined a chorus of players and coaches across sports who, for decades, have blamed artificial turf for injuries ranging from sprains and strains to tendon ruptures.

As a physical therapist, researcher and director of performance and sports science, I help elite athletes minimize injury risk and maximize performance. It’s always difficult to tell whether an injury could have been prevented had someone not been playing on a certain surface - particularly because muscle and tendon strength, pliability and stiffness usually play a much more important role.

However, some studies have linked playing on artificial turf to injury risk, though the risk tends to be limited to a few body parts.

The grass is always greener?

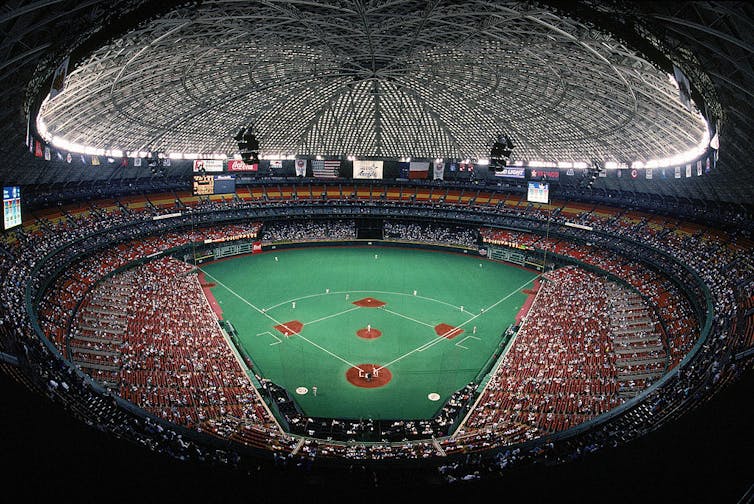

In 1966, Houston’s Astrodome became the first major sports venue to install synthetic turf. It was originally called “ChemGrass,” though Monsanto, the company that invented it, later rebranded its product as “AstroTurf” due to its association with the Astrodome.

Not everyone was jazzed about the cutting-edge carpet.

“Imagine that – a [US]$45 million ballpark and a 10-cent infield,” groused Chicago Cubs manager Leo Durocher. Players said the surface didn’t have the same give as grass – making diving for balls a risky endeavor – and claimed their knees deteriorated from the daily grind of playing on the harder surface.

The technology has come a long way since then. Today’s synthetic turf systems have shock-absorbing technology and glasslike fibers that essentially mimic natural grass. Its proponents argue that they’re low-maintenance, cost effective and more durable.

Some athletes disagree. Not only do they point out that artificial turf is still a lot different to play on than grass, but they also question the league’s commitment to safety over saving money.

So what does the evidence show?

There have been studies looking at the rate of injury on different playing surfaces. A handful have found that the overall incidence of football injuries is significantly higher on artificial playing surfaces.

However, orthopedic resident Heath Gould – a former college football player – led a review of existing studies and found that most studies identified similar rates of injury on natural grass compared with artificial turf. There have even been a few studies that reported a higher overall injury rate on natural grass.

Interestingly, the incidence seemed to be related to specific body parts. There was a higher rate of foot and ankle injuries on artificial turf – both older versions and newer ones – compared with natural grass. And a recent meta-analysis observed that the overall incidence of injuries in professional soccer is actually lower on artificial turf than on grass. It concludes that the risk of injury can’t be used as an argument against artificial turf when considering the optimal playing surface for soccer.

These findings suggest that while playing surface is important to take into account when assessing injury risk, other factors must be considered.

The human factor

The human body is a kinetic chain that consists of body segments linked together by joints. Those joints need to work together to create and dissipate forces needed for us to move and perform athletic motions.

Any chain, however, is only as strong as its weakest link. The muscles, ligaments and tendons in our bodies play an important role in supporting those links.

For athletes, the stakes are even higher because of the incredible power and momentum they are able to generate and absorb. They rely on muscle, tendon and ligament stiffness in order to take advantage of the elastic energy they create. Like a spring or rubber band, when a muscle is stretched, its stiffness helps create elastic energy that can then be used with a muscle contraction to help athletes run, jump, accelerate or decelerate.

Research I conducted with colleagues found that injuries can occur when there is too much stiffness or compliance in these tissues. In fact, we’ve found that Achilles tendon ruptures in professional basketball players tend to occur when the ankle flexes beyond the muscle and tendon’s ability to withstand the forces incurred with certain maneuvers.

Certainly, several other variables factor into injuries: muscular strength, power, flexibility, body type and tissue elasticity.

What gives?

Playing surface is another important aspect of this equation.

Think about the contact point between the athlete and the surface that they’re playing on. This represents an additional link in the chain because forces must be exchanged between the player and the ground.

As Isaac Newton noted, “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.”

The playing surface must be firm enough to allow an athlete to push off to accelerate or jump. At the same time, the surface must be compliant enough to be able to absorb forces when a player lands or slows down. There is a sweet spot between the ability for playing surfaces to offer enough resistance and support, but also absorb forces.

Therein lies the question as to whether artificial turf is appropriate and safe enough for athletes. The research might be somewhat hazy, but Rodgers’ Achilles tendon rupture did occur in a part of the body that is correlated with more injuries on artificial turf.

It’s encouraging that playing surface technology continues to evolve. But replicating mother nature isn’t easy.

Philip Anloague ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.