An outstanding variety of Indian historical textiles in silk have fascinated the world for centuries. They comprise well-known private and public collections in museums in the country and abroad. But little is known of the sources and histories of the yarns used in them. In a scenario primarily dominated by the histories of cotton and its role in shaping trade, wealth and colonisation in the subcontinent, Aarathi Prasad’s Silk — A History in Three Metamorphoses opens up exciting new areas for enquiry and research.

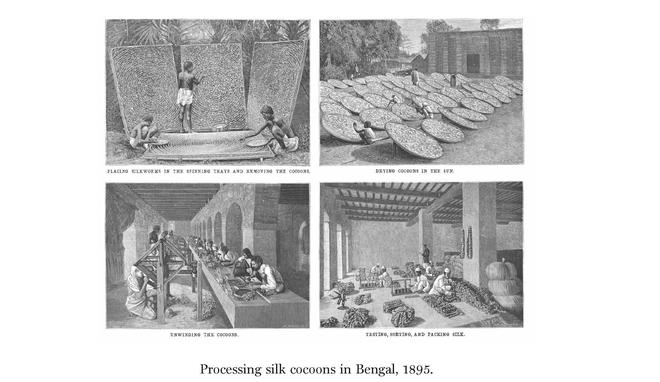

To researchers and scholars, the book presents new information guided through fresh references as well as those markers that they may be familiar with: findings in excavated sites of the Harappan civilisation, the fabled silk route, documentation of Indian fabrics by British colonial authorities, and the Great Exhibitions in Europe. Beyond India, the breathtaking sweep of this book presents never-before published information and insights on the histories of silk across the globe — from the Americas, Europe and Africa to other parts of Asia — covering events from ancient times to the contemporary. The selection of accompanying illustrations greatly help visualise many of the observations that the author brings to the book’s narrative.

Ambitious in its intention as well as scope, meticulously researched, and superbly written, the author converges the worlds of archaeology, molecular research and biology, design and art with a seamlessness that can only emerge from an innate passion for the subject. In doing so, she brings alive personal journeys, triumphs as well as failures — of explorers and adventurers, researchers and scientists, makers and artisans, businessmen and entrepreneurs.

Edited excerpts from an email conversation:

You have written in the past about medicine. What inspired your interest in the histories of silk?

My interest in silk actually started with the future of medicine. In ancient India, China and Greece, silk was used as surgical sutures; Genghis Khan provided thin silk vests to soldiers to reduce damage from arrow wounds. It was well known by then that silk had healing properties. But when I heard about new technological applications of this ancient material, I was amazed. It is being used as soft-tissue fillers and for the treatment of vocal cord paralysis, and trialled as replacement examples for cartilage, bone, and artificial blood vessels. For well over a decade it has been used to temperature stabilise drugs, which has important applications in also stabilising vaccines, for instance, that would normally need refrigeration. And these are just the more ‘obvious’ applications. There are also other ideas, from holograms and electronic-human interfaces, to flexible and biodegradable implantable electronics that record brain signals, and edible, consumable sensors to track fitness and nutritional quality of food. As a natural animal protein that is related to keratin, similar to the protein in our hair and nails, it can be made to evade the immune system and be accepted by our bodies. And it can be produced in a sustainable way, and is entirely biodegradable.

Varieties of wild silks such as eri and muga are often referred to as ahimsa silks, or non-violent fibres, since the worms are not killed in the process of their reeling. What are your views on this?

It is an important point that materials taken from nature, whether they are made by plants or animals, should be harvested in the most sustainable way to protect them and the planet, and us, ultimately. Humans are so wasteful. Nature reuses everything. We need to learn from that. The Chinese domesticating the silk moth [bombyx mori] was a remarkable achievement. At the same time, some 4,000 years ago, in the Indus Valley, silks were being produced too. These threads were from the cocoons of moths of two or three distinct types. One type may have originated from the tropical west coast of India, and the other two certainly from Assam — 1,000 km away from the ancient Indus cities of Sindh and 2,000 km away from Punjab.

Some of these threads show evidence that they were harvested from cocoons inside which the worms had been killed, just as regular domesticated silkworms are, but other silks show evidence that they were made without doing this. If the moth is allowed to escape the cocoon, you will not get the sheen and continuity of one seamless thread. But what some see as flaws in the smoothness of ahimsa silks, others value as a texture to the fabric. It depends really on our view of what is beautiful and what is precious. And what needs to be destroyed along the way for our preferences. We are at an inflection point, on this planet, so we need to start making choices that tread more lightly.

You include fibres extracted from sea molluscs and spiders. What led you to take such an approach?

When I first started thinking about silk I didn’t know much beyond the famous Chinese silk moth, which the beautiful Kanjeevaram saris my mother and aunts wore were made from; and certainly not beyond moths in general. But silk is a truly global story — there were wild moths used in antiquity across the world, but also metre-tall molluscs in the Mediterranean, and giant spiders in Madagascar and the Pacific, who weave huge golden webs. For technology, spider silk has been the most coveted in terms of tensile strength [the maximum amount of stress a material can endure before breaking]. It is five times tougher than steel. Mollusc silk is incredible because it is self-healing, so it has inspired the development of new synthetic materials such as adhesives for foetal surgery, and self-healing polymers.

Know your silks

The writer is a Delhi-based curator of textiles.