This time last year I walked into the offices of a car rental company in Queens, New York, to hire a vehicle. Quite unexpectedly, I ended up in a rather animated debate, not about the sky-high price of rental insurance contracts but about share prices.

As I filled in my forms, I let slip that I was a financial journalist. Before I knew it, I was bombarded with questions from the staff — and even other customers — about the share price of an electronics retailer called GameStop.

The rental staff told me cheerily that they had never owned stocks before. But in 2020 they had joined the trading app Robinhood, just as an estimated 10 million other Americans were opening brokerage accounts that year.

After swapping tips with each other and fellow traders on social media, they got busy grabbing securities they liked during lockdown. “It’s as easy as a video game,” my rental agent told me, adding that she really liked the way the app showed confetti exploding on her phone screen whenever she made a trade.

Fast forward 12 months and it’s hard to imagine a similar conversation happening now. After starting January 2021 at below $20, GameStop’s share price peaked at about $400, before crashing to $40 (it’s now trading at about $107). Many of the new-wave retail investors lost out. The wild swings — and a partial trading halt on Robinhood — prompted an inconclusive congressional investigation into the company, and, while Robinhood continues to expand, the story hasn’t really hit the front pages since.

On the anniversary of all this drama, however, it is worth reflecting on what we could — and should — have learnt.

Financial history shows that retail investment frenzies like this usually occur near the end of a bubble

First, financial history shows that retail investment frenzies like this usually occur near the end of a bubble. As the American politician Joseph P Kennedy is reported to have said, “If shoeshine boys are giving stock tips, then it’s time to get out of the market.” Someone making a similar observation about the Queens car rental staff a year ago would have been premature. GameStop’s surge may have been short-lived, but the S&P 500 index has risen by 30 per cent since then. Yet while it is never easy to call the end of a bubble, I would bet that we are nearing a top.

After all, a key reason why asset prices are elevated is that central banks have pumped oodles of money into the system; the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has soared from $2tn to $9tn in the past decade. This has created some peculiar data points: an index compiled by Goldman Sachs that measures financial conditions is at record loose levels (meaning the system is drowning in cash). This tsunami of money has also left investors fearful of missing out on soaring asset prices, sparking dramas like the GameStop one. But the Fed is now trying to reduce its support, which could easily spark a shock and make Kennedy’s shoeshine advice a bit more relevant.

The second force is consumer behaviour. The GameStop saga revealed the degree to which finance is being reshaped by digitisation. It also showed the appeal of customisation. In the 20th century, retail investing was often a slow-moving, stodgy affair and consumers could generally only choose pre-packaged options created by finance companies. In other words, should I buy this mutual fund or that one?

If that was like deciding whether to play the A-side or B-side of a vinyl record, then apps such as Robinhood are more like a Spotify playlist, offering investors the chance to pick and mix securities however they wish. The sense of individual choice has been empowering.

At times, however, that may be an illusion. After all, Robinhood stopped executing some customer orders at the height of the crisis. It sold data on customers’ trading flows to other players such as Citadel Securities. But that doesn’t change the fact that today’s consumers expect this choice — and this has encouraged more people to become investors.

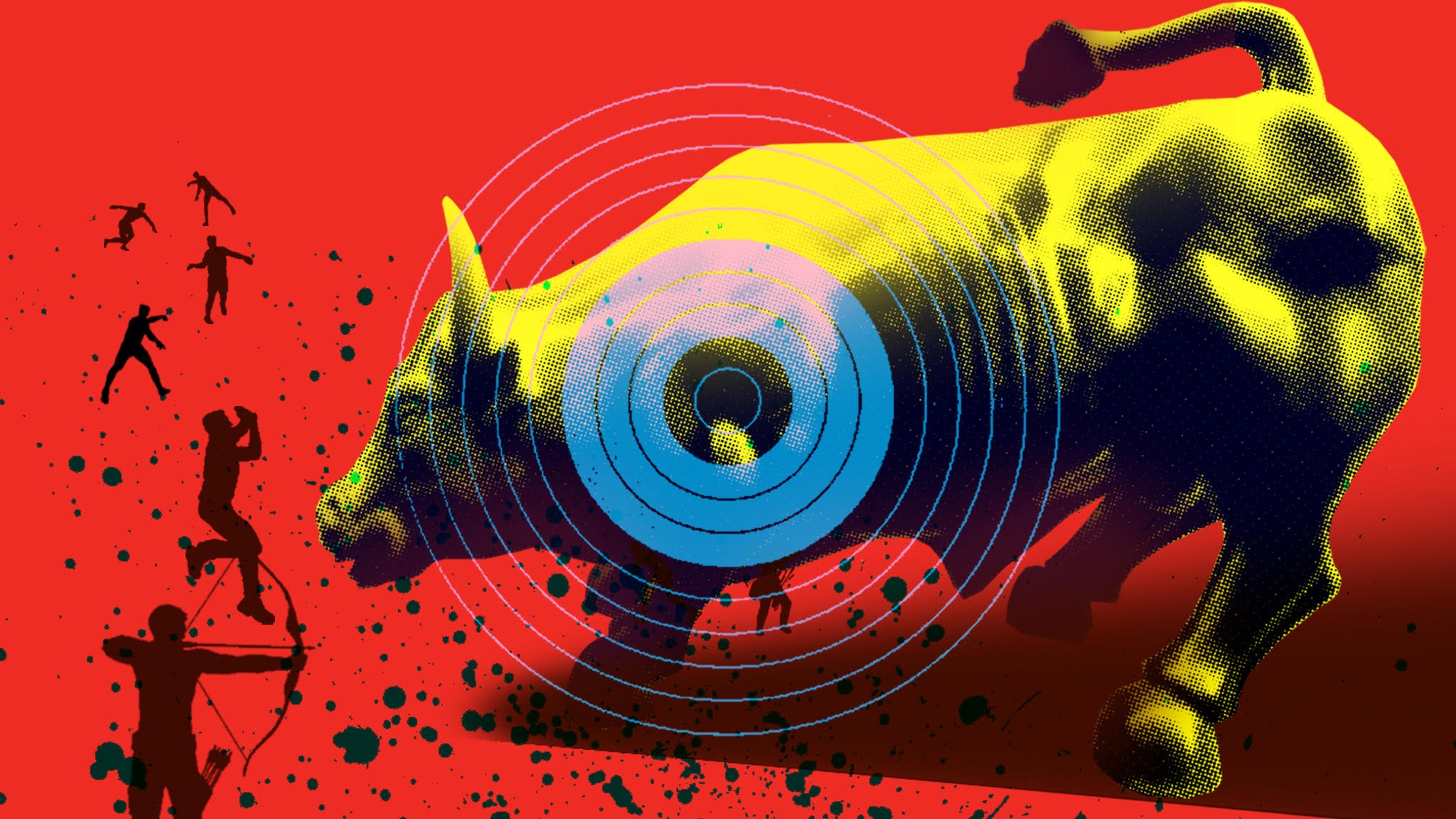

The third force I’ve been considering is populist anger. In his recent book about GameStop, The Antisocial Network, Ben Mezrich describes how ordinary Americans were sucked into the wild trading frenzy because they resented the wealth and power concentrated at the top of the financial system, and because they felt excluded from it. Once they entered, they discovered that the force of the digital crowd was so powerful that it created a “first revolutionary shot — fired directly at Wall Street”, as Mezrich says. “Historically revolutions fed by anger tend to go in the same direction… once the pillars start to shake, the walls inevitably fall.”

Right now that prediction may seem overblown. Some of the institutions attacked by the social media traders, such as Citadel Securities, are actually stronger than they were a year ago. But as the world faces a potentially turbulent year, those messages from GameStop matter, particularly since it will probably be small investors who get hurt when the bubble bursts.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022