If for some reason a 372 mph bullet train is too sluggish for your taste, you may be in luck: A new super speedy plane-train “hybrid” called FluxJet could (theoretically) become available within the next few decades. It aims to travel over 600 mph, a bit faster than the average commercial plane and around three times quicker than most high-speed trains, according to Canadian-French transportation tech company TransPod in its announcement last month.

For its first journey on Transpod’s hyperloop, a high-tech system that uses magnets and electricity to send a levitating capsule racing through a steel tunnel, the FluxJet will travel between the Canadian cities of Calgary and Edmonton (a project that will cost $18 billion to complete.)

FluxJet will take advantage of a hyperloop system for its pod. This science fiction-esque technology hasn’t exactly had the best press in recent years, thanks to a string of high-profile mishaps — take the finding that the capsule could possibly kill you, or the fact that a hyperloop project sucked up California funding for public transit. But TransPod holds its own among the gaggle of emerging hyperloop projects due to several distinctive features, Sebastien Gendron, TransPod co-founder and CEO, tells Inverse. “We always say the devil is in the details,” he adds.

How the plane-train works

A hyperloop transit system consists of a vacuum-sealed tube that zooms through a ground-level or underground tunnel at nearly the speed of sound (companies have boasted speeds around 600 and 700 mph). To avoid any friction and zip along quickly, hyperloop vehicles are designed to levitate.

TransPod looks a bit different from the various hyperloop projects currently in development, including one from Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and Elon Musk’s Boring Company.

For instance, to hold the vehicles in place, both Virgin and the Boring Company use a hyped-up technology called magnetic levitation (commonly referred to as maglev) — essentially, a series of magnets lining the tunnel repulse magnets attached to the train. It’s somewhat similar to how, despite your best efforts, you can never quite get two magnets to touch.

This technology is already employed on fancy high-speed trains in China, Japan, and South Korea, which can run over 600mph. Meanwhile, Amtrak in the U.S. can only reach 150 mph. But incorporating magnitudes of magnets can be extremely expensive, Gendron points out. After all, the Shanghai maglev train cost around a whopping $1.2 million to build and probably hemorrhages money, according to a Slate article. We already have evidence that hyperloop systems will cost a fortune: In 2016, leaked documents revealed that the proposed Virgin hyperloop line between Los Angeles and San Francisco would cost about $84 million to $121 million per mile to construct.

That’s why TransPod will flip the script and use attraction, not repulsion, to float the FluxJet: The steel tunnel will attract the magnet attached to the top of the vehicle and keep about a centimeter gap between the tunnel and the FluxJet.

Companies also differ in how they actually power their futuristic tube trains. The Virgin and Boring Company hyperloop concepts both run on batteries, but Gendron says batteries are too heavy and can be unreliable. “It’s not a viable solution on our own end,” Gendron says.

Instead, TransPod aims to incorporate an electrical arc, somewhat similar to a component of subways, that shoots electricity on a continual basis into a FluxJet capsule. The system is also equipped with predictive suspension, meaning that the vehicle’s electromagnetic field can react to bumps in the infrastructure and ensure a comfortable experience for riders (who don’t want to feel like they’re in a “washing machine,” as he puts it).

A history of hyperloop hysteria

But how close are we to hopping on the hyperloop for a quick weekend getaway? The closest thing we have to a functioning hyperloop nowadays is a lone 500-meter Virgin tube in the Nevada desert (which can provide a thrilling 15-second ride) and the Boring Company’s test tunnel in California, along with plenty of studies in the works. But it’s far from a new idea.

The first glimpse of today’s hyperloop originated in the late 18th century, when English mechanical engineer and inventor George Medhurst proposed an engine that can push vehicles with compressed air. Sound familiar?

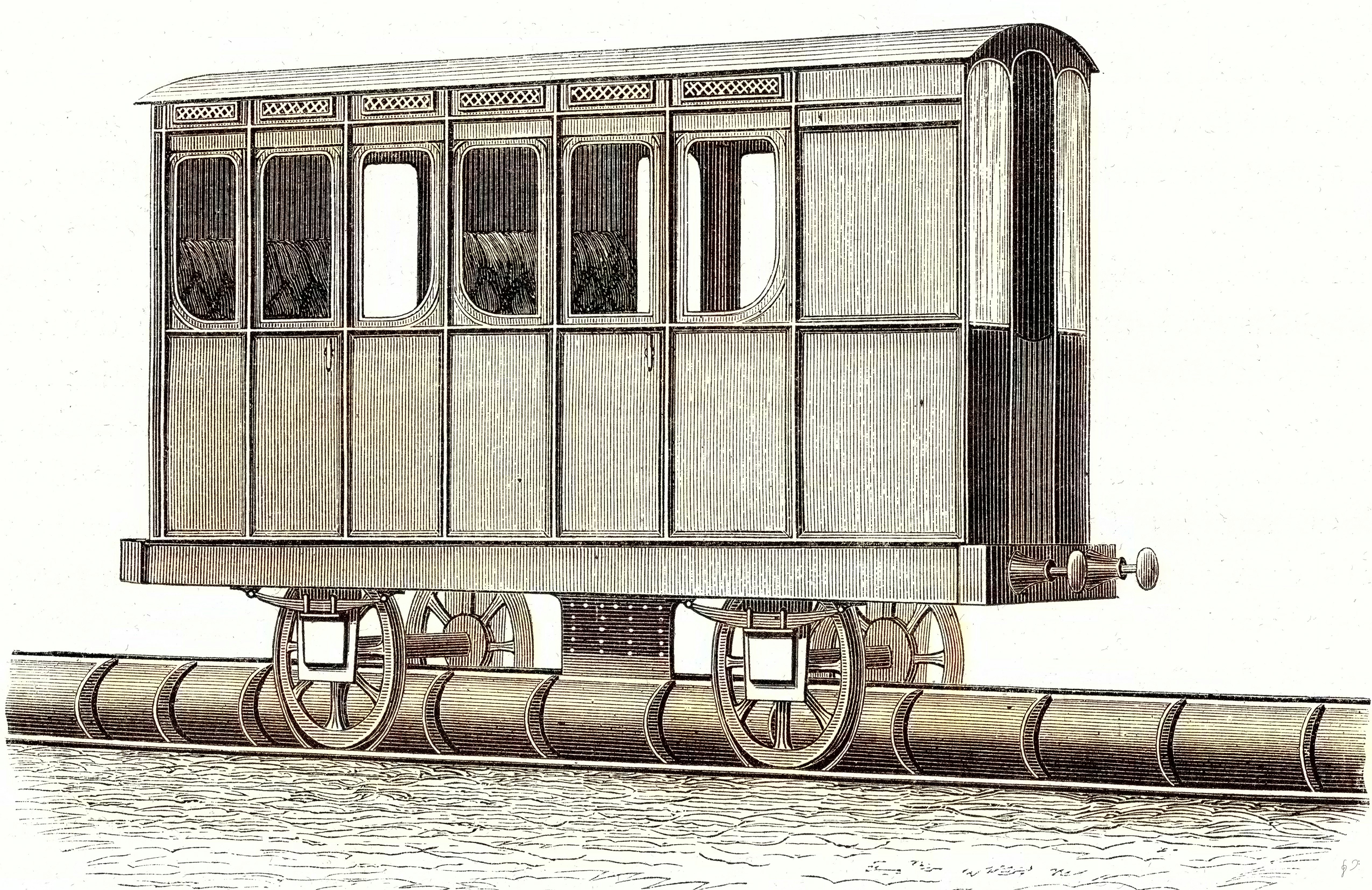

Then in 1844, Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel built a 20-mile-long “atmospheric railway” that relies on atmospheric pressure to push the train forward.

After that, not much happened for nearly two centuries. “The technological, engineering, economic, and political challenges kept it from getting off the ground, in a manner of speaking,” Arthur C. Nelson, a professor emeritus of urban planning and real estate development at the University of Arizona, tells Inverse.

Musk drew inspiration from these whimsical plans in 2013, when he published a white paper that outlines what we know today as the hyperloop. Musk encouraged other businesses to pursue the idea, inspiring a flurry of ventures around the world.

Today, the hyperloop attracts its fair share of critics. Besides the exorbitant costs involved in building and likely maintaining them, not everyone is sure they can even be built (at least not within the next decade, as Virgin has promised). After all, the major players have encountered hiccups when it comes to funding, attracting talent and staying on track with deadlines, The Verge reported. There are also technical problems, including the possibility of steel tunnels melting in high temperatures. Nelson says we’ll likely have to wait until the end of this century (perhaps up to 300 years after Medhurst’s first patent). “Robert Heinlein wrote science fiction about it in 1956 but the application of the technology is still science fiction,” he says.

Even if the hyperloop does succeed in the foreseeable future, it doesn’t seem very practical. Experts commonly point out that the carrying capacity will be relatively low. That’s because in most countries trains can’t run within each other’s braking distances, which is a problem since many hyperloop capsules can only fit around 30 to 40 passengers. FluxJet proposes to up its game a bit with a capacity of up to 54 passengers.

But compared to a hyperloop system, today’s high-speed railways can transport up to five times more people per hour in either direction. In fact, this past winter Virgin Hyperloop abruptly shifted its focus to carrying freight, suggesting that passenger capsules may be a ways off.

What’s next

Despite the controversy surrounding the growing number of projects in the works, Gendron is optimistic about TransPod’s future. He hopes to have a test site constructed in France by early next year, along with a full-size test track in Canada by 2025, which will require a larger FluxJet vehicle (the company has so far only built a small model). He also envisions additional routes in Canada and in the U.S., along with the UAE, Australia and Saudi Arabia.

Gendron acknowledges that he’s working on a tight schedule, and sees several roadblocks ahead (beyond the technical details) such as securing government authorizations and ensuring minimum impact to surrounding ecosystems. He hopes that the infrastructure can encourage biodiversity, somewhat like an artificial coral reef.

And unlike many forms of high-speed transit, TransPod could offer relatively affordable tickets. By cutting down the infrastructure costs associated with maglev and constructing a simple steel tunnel, Gendron claims he will try to keep ticket costs low — similar to how Elon Musk promised a $20 ticket for the Los Angeles to San Francisco route. He estimates that a one-way ticket between Calgary and Edmonton would cost around $90 CAD. “We want to avoid it being a transportation system for rich people,” Gendron says. “I wanna be able to find the right balance and make sure that the system will profit anyone.”

Editor's note: On August 8, 2022 this post was updated to correct a grammatical error in a quote.