When three Iraqi artists were invited to exhibit their work at this year’s Berlin Biennale, the organising themes – decolonisation and repair – promised to give voice to a subject the trio understood more than most.

Each had grown up in the shadow of America’s 2003 invasion, and their art now wrestles with its aftermath. A film by Layth Kareem explored community trauma and healing. Sajjad Abbas brought a banner emblazoned with a picture of his eye, which he had once hung opposite Baghdad’s heavily fortified Green Zone, meant to symbolise the Iraqi experience of watching the $2tn occupation.

But when the group walked into the exhibition hall, a different installation about Iraq loomed largest: a series of war trophies taken by US soldiers – photographs of the torture and sexual abuse of Iraqi prisoners inside Abu Ghraib prison – presented by a French artist to shock the gallery’s visitors.

“There was just this idea that this is what’s good for us – this is what’s good for the world – just to see these images again,” says Iraqi American art curator Rijin Sahakian, who introduced the artists to the exhibition organisers.

The episode brings uncomfortable questions into focus: who has been allowed to narrate Iraq’s recent history on the world stage? And where is the work of the Iraqi artists who are living it?

“All we’ve asked for is to have a voice that isn’t spoken over,” Sahakian says. “The Iraqi artists participating were just grouped together with the photographs.”

Although a small number of Iraqi artists exhibit their work internationally, visual representations of the country are usually dominated by western news media.

Iraq’s artists were once among the region’s most famous. In 1951, Jewad Selim and Shakir Hassan Al Said founded the Baghdad Modern Art Group as they sought a distinctive Iraqi artistic identity, mixing modernist styles with local history and motifs.

But over time their work was co-opted by political forces, and by the late 1980s, Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party dominated the art scene and used it for propaganda.

Today, Iraq’s government is among the most corrupt in the world. Public services are failing, the electricity grid is on its knees, and extreme heat is ruining land that once brought food and employment.

As a new generation of Iraqis work to tell their own stories through contemporary art, they face hurdles at every turn.

Baghdad’s yellow-brick Institute of Fine Arts teaches only classical methods, so students who branch out to new mediums must use whatever space they can find. They work at home, on rooftops or together in small studios, often with limited funds and scant storage space for the pieces they produce.

Private galleries exist but are hard to break into, often requiring personal connections and money for publicity. Grant funding requires applications in fluent English. When international opportunities arise, many artists find that they cannot get visas to go to their own exhibitions.

“It takes a lot of networking and time,” says Hella Mewis, a German-born Baghdad art curator. “You need to know the system, the art market and it’s very complicated.”

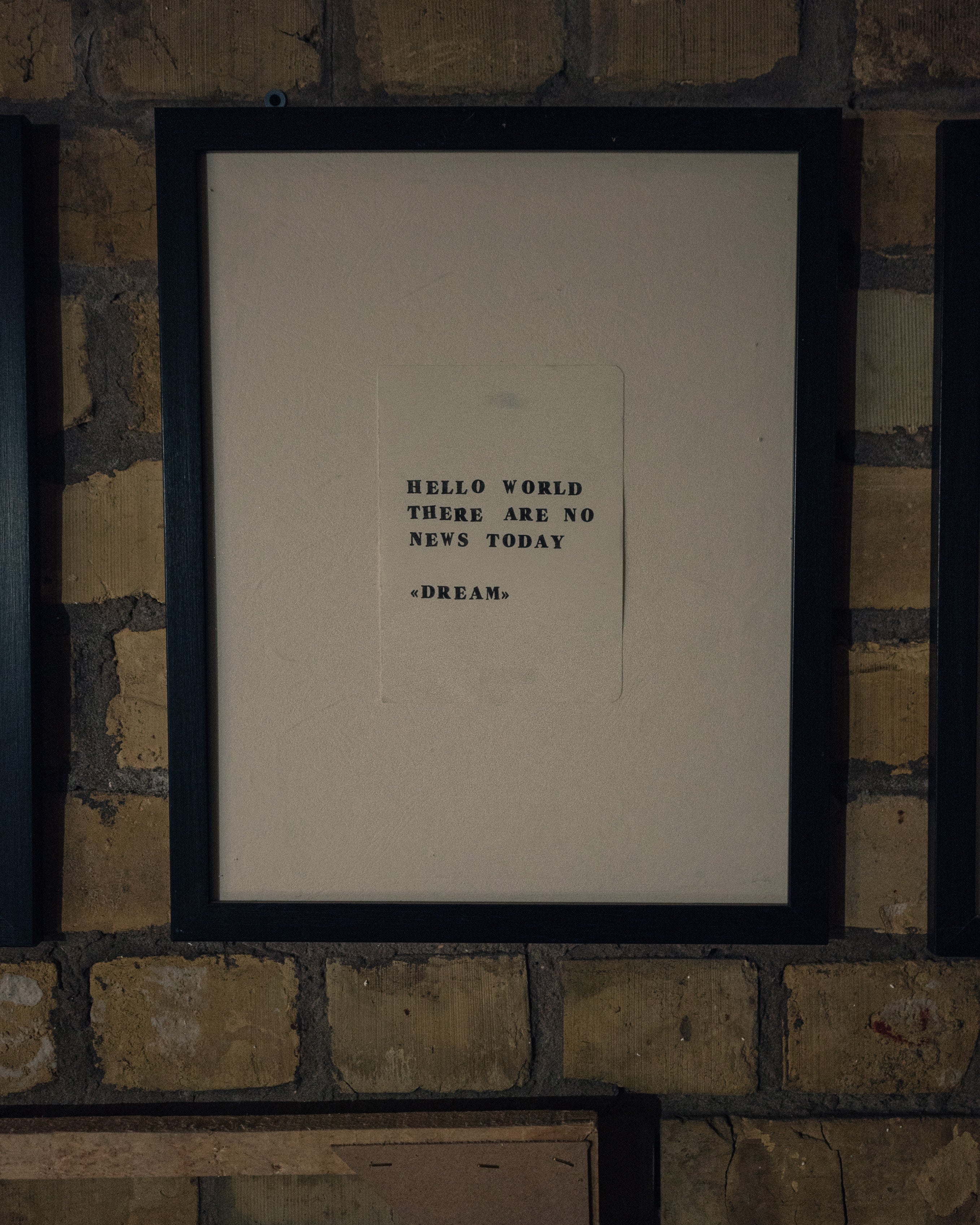

But the city has one haven: Beit Tarkib, or the House of Installation, tucked away in the historic district of Karrada between the old Jewish houses and tall palm trees. Founded by Mewis in 2015, the venue is dedicated to nurturing contemporary art, with studios for the artists and spaces for young people to learn drawing techniques, ballet and musical instruments.

From every wall, the artists’ work presents the contours of Iraqi life. Photographs and sculpture chart the changing face of Baghdad. A Sumerian-style house brush invites visitors to sweep away the judgment of a sometimes closed and conservative society. In one room, an oil painting of a soiled white shirt captures intimate details about what a person experiences when a car bomb rips an ordinary day apart.

When a Palestinian artist visited recently, he described the tone of the work as distinct from the rest of the region, Mewis recalls. “Here, he said that with each artist, you see that they are Iraqi. There are different styles but you don’t see the western influence,” she says. “This is the best compliment we have ever received.”

In April 2019, they spread their artwork across Abu Nawas Street’s public gardens, and the exhibits felt like a cry against corruption and suffocated ambition.

With hindsight, Mewis realised, it took the pulse of a society on the verge of revolt. Seven months later, small protests against state corruption turned into a full-scale uprising against the political system, and artists joined Iraqis from every walk of life.

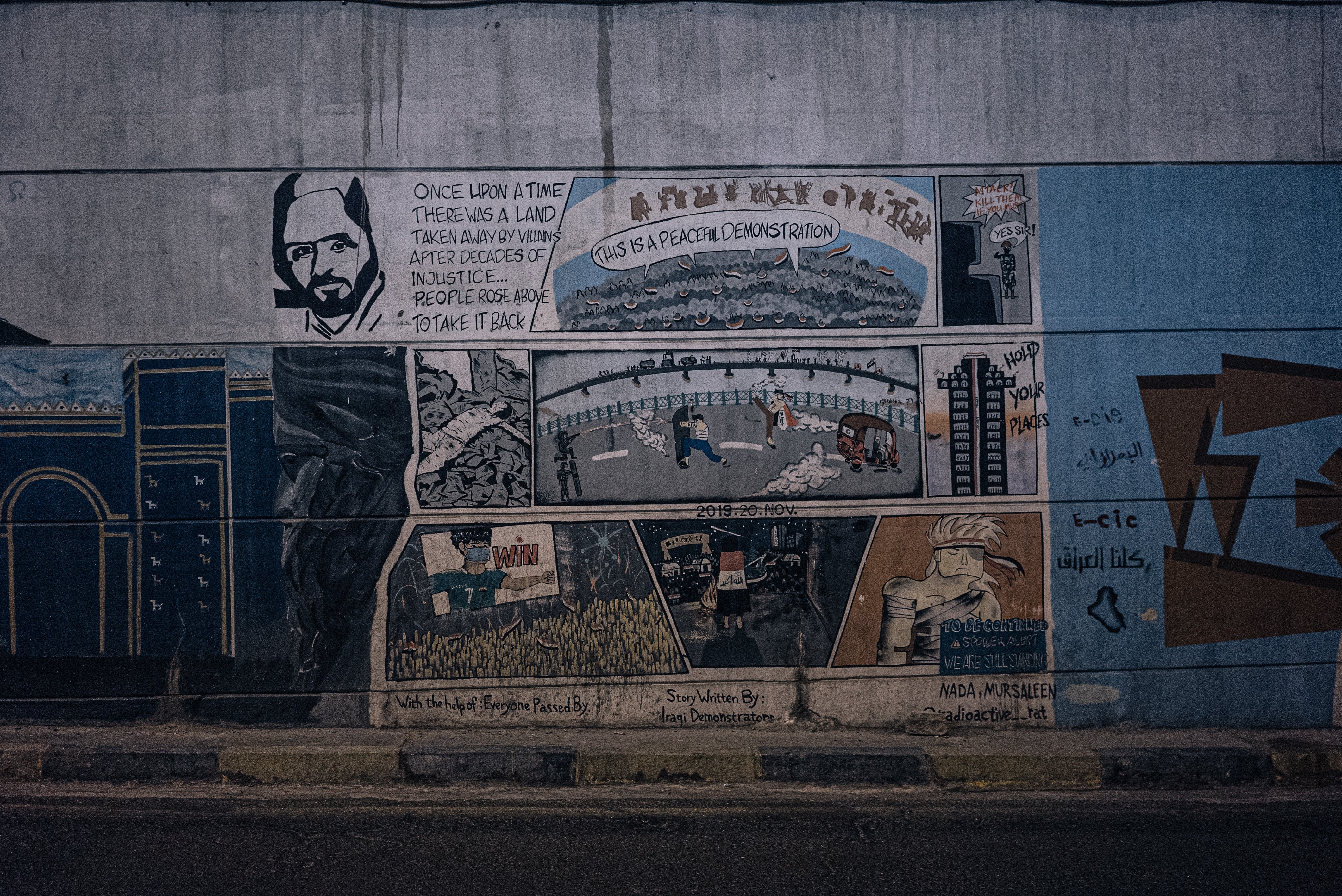

After more than 600 people were killed in a government crackdown, the protesters etched that history on the walls. Near Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, a grey-stone underpass became a riot of colour. Murals showed the names and faces of the dead, in gold calligraphy and black-and-white sketches.

Zaid Saad was among the artists exhibiting at that 2019 festival, and the 31-year-old’s work – suitcases moulded from concrete – focused on the rejection that Iraqis face when trying to reach Europe or America.

One day he wants that work to be seen in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

During his student days at the Institute of Fine Arts, he made plans with his friends for future projects. But amid growing economic despair, at least 10 of them boarded migrant boats bound for Europe in 2015. Some of the group died at sea. Others made it, but fell out of touch. Millions of Iraqis have left the country since 2003, fleeing violence and poverty.

In the entrance hall of Beit Tarkib is a work that Saad used to reflect that loss: a white door from near Rasheed Street’s central bank has been attached to the wall, and half a bicycle wheel protrudes toward the viewer from the wood.

“This is about our plans, and how they stayed with me,” he says, looking down at the half-wheel’s spokes. “The other half crossed to another world, and I can’t see what’s over there.”

Saad makes his sculptures outside now that the summer heat has ebbed. A floodlight lights the patio like a stage. The process is quiet, sometimes meditative, as he melds water with cement and the mixture coats his hand like a glove.

On a recent night, a driver was blaring his car horn on the street, but Saad was wrapped up in his work. “I think about so many things as I do this,” he says.

His latest piece for an exhibition focused, again, on migration, and his friends were still on his mind. “Some of them trusted me so much they told me they were leaving before they told their families,” he says.

His work was almost done, and he poured the last of the concrete into its mould.

“I always feel sad when I read news about the refugees,” he says. “Is it such a big deal to let people in?”

© The Washington Post