With The Passion of Private White, Don Watson has written a witty and compassionate book about friendship, Indigenous self-determination and people under stress.

“Private White” is Neville White, an anthropologist and Vietnam veteran who has spent two months a year since 1974 in Arnhem Land, as a guest of Yolngu families residing at the Donydji community.

Watson explains:

For the last forty years, all the Indigenous people of north-east Arnhem Land (Miwatj) have been known as Yolngu – which means “person” or “people” or “human being”. They number about 3000 and all are members of one or other of several dozen intermarrying culturally connected clans.

Review: The Passion of Private White – Don Watson (Scribner)

Yolngu self-determination

Donydji is an experiment in self-determination – that is, in Yolngu choosing the degree and forms of their involvement in Australian institutions. Before his first visit to Donydji, White was told that

alone among the Yolngu clans, the people living here had never left their lands. Here, and only here, would he find a clan whose traditional knowledge was intact.

Two policy changes in the mid-1970s afforded a greater margin of choice for Yolngu, including the residents of Donydji. In 1976, the Fraser government’s Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act gave Yolngu title to the entire Arnhem Land Reserve, including the right to veto mining.

Until 1975, unemployment benefits were not available to remote Aboriginal people (as, in the absence of a local labour market, they were not seen as seeking employment). Without needing a change in legislation, the Department of Social Security decided to make unemployment benefits available to these previously excluded people.

This created a new and substantial income stream for remote communities such as Donydji, and many of them began to avail themselves of it in the form of the Community Development Employment Program. This income relieved them of the pressure to say “yes” to economic development.

Donydji became a permanent camp in 1971. Sitting down at Donydji was driven by the desire of certain Ritharrngu and Wagilak families to safeguard Country from exploration – such as test-drilling that had violated a site in the late 1960s. Donydji is strategically located on a road and an airstrip graded to service mining exploration.

So, to preserve their traditional lands, the families at Donydji have modified their way of life. Erecting shelters and demanding basic services such as schooling and access to manufactured goods, they have become sedentary.

You can learn all this by reading White’s history of Donydji – downloadable (free) from Australian National University Press. He describes some of the consequences of Yolngu becoming sedentary.

At Donydji, Yolngu live on a combination of what they can forage and what they can purchase, and they seek whatever material support governments and citizens can offer them. They are gripping their country and they are gripped by it. As well, they are gradually losing some knowledge that had been essential to nomadic foraging.

Read more: Paul Daley's Jesustown: a novel of lurid, postcolonial truth-telling

An anti-Vietnam War veteran

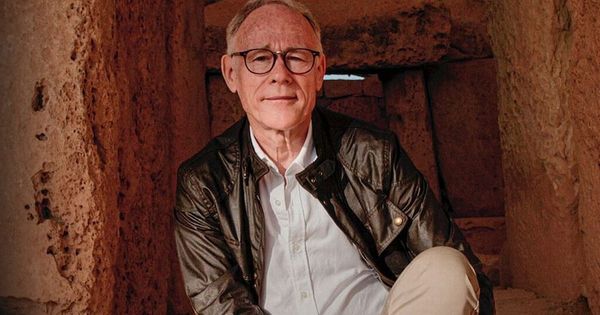

What Watson brings to this story is his compassionate, sardonic appreciation of White (an old university friend), his Yolngu hosts and the Vietnam veterans who have assembled over many dry seasons as Donydji’s volunteer construction gang. White knows these men because he served with them. So this is not only a book about Yolngu self-determination.

Labelling White “an old-school Australian”, Watson explores his own affinity with this cohort of ageing white men whose troubled bond is their service in a war he experienced only through the antiwar movement. At the same time (and from a greater distance), Watson narrates his experience of getting to know Yolngu, through his many visits to Donydji. Watson’s well-honed and affectionate sense of the absurd flavours every anecdote. But the deeper subject of this book is what binds and divides men.

Neville White grew up in working-class Geelong. His father, Leo White, was a champion boxer and trainer of Aboriginal fighters. Becoming Neville’s friend brought young (“sport-addicted”) Don closer to a milieu he had reverently imagined.

Don and Neville could agree, when they met at university in 1968, that Australia should not be committing troops to Vietnam. But by then, Neville had already served. Accepting conscription (in the third ballot, on September 10 1965) while disputing Australia’s commitment, he had spent the second half of 1967 as an infantryman.

Bonds forged with other soldiers outweighed – in their moral force – Neville’s rejection of Australia’s policy. “He would hardly be the first,” Watson comments, “to fight a war in which he did not believe.” White’s demobilisation was not of his choosing either. The bitter politics of conscription had made it prudent to limit conscripts to two years of service.

His sudden extraction from the battlefield left White feeling like he had deserted his comrades. Coming home was almost as baffling as the fighting itself. “For Neville’s experience of the battlefield the anti-Vietnam War movement had no affirmative words, or sympathy, or respect.”

That sense of failure still agitated White in a December 2021 conversation recounted by Watson. However, by then White had found a way to remake battlefield mateship – annually mobilising several of his old platoon as a volunteer construction gang at Donytji. A day’s hard work – punctuated by “chiacking” – concluded with mutual solicitations, as the men reminded one another to take the medications required to keep post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at bay.

Neville White is thus the hinge connecting the two “tribes” (the Yolngu residents and the visiting Vietnam vets) that annually find common purpose at Donydji.

Read more: The forgotten Australian veterans who opposed National Service and the Vietnam War

At ease with anthropology

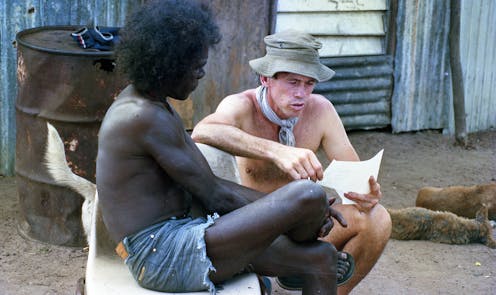

But in 1974, when White began to camp and observe at Donydji, he didn’t set out to connect the two parts of his life – soldier and anthropologist/guest – in this way. His early mode at Donydji was respectfully detached, in the name of science. The data he collected included fingerprints (a measure of genetic distribution). Some now revile anthropology as colonial zoo-keeping.

But Watson is not only at ease with White’s vocation; he admires the ethnographic tradition. His exposition of Yolngu ways draws on White’s predecessors, such as Lloyd Warner (a US sociologist and anthropologist who visited Arnhem Land in the 1920s) and Donald Thomson (an anthropologist who worked with the Yolngu as an investigator, advocate and mediator, in the 1930s).

Ethnography thrives on partnerships between researcher and teacher. Tom Gunaminy Bidingal, the senior man at Donydji, agreed to walk the Country with White and to answer questions, while remaining “cagey”. White “had always wondered if Tom was unforthcoming because he didn’t want to divulge secrets, or because he didn’t want to simplify matters that were too complex or too ambiguous to settle on definitively”.

Starting his doctoral research in 1971, White asked how physical environments determined Aboriginal social organisation – for example, “the relationship of the dialects to the drainage basins”. This “human ecology” approach to Aboriginal practices of social connection and disconnection emphasises the physical determinants (in geography and in human and non-human biology) of a society’s strategy of survival.

Within anthropology, the human ecology approach peaked by the 1980s. It has been displaced by accounts of Aboriginal civilisation that dwell on human agencies (both poetic and political), and that are not limited to reconstructive modelling.

While observing the practices and knowledge that enabled the Yolngu’s long-term survival, White found it impossible to ignore the rapid attrition of his Donytji hosts’ health. His scrupulous non-interference finally collapsed – unravelled by compassion – when he gave antibiotics to a man suffering a gum abscess.

Donytji’s suffering thus compelled White to become an agent of the unprecedented “human ecology” of Yolngu sedentarism. That is, White - his equipment, his knowledge and his capacity to advocate - became one of the resources the Donydji mob now had at their disposal, as they adapted their lifestyle. To ameliorate a pathogenic environment, he became:

project manager, facilitator, money raiser, go-between, advocate, patron. Benefactor, urger – altruist.

His diary of ensuing interactions with people and organisations beyond Donydji provides Watson with much material. The sentimental affinities of author and subject are evident in these stories, as no “white functionary” is spared mordant report.

From incidents so deftly told, individuals emerge. White functionaries, visiting volunteers and Yolngu are named. White’s academic publication practice has included giving pseudonyms to some Yolngu.

To name is to take an ethical risk – for while the named visiting veterans are likeable, helpful, humorous blokes, some of the Yolngu are problematic people (from any point of view, including Yolngu) and some are people with problems that they cannot easily solve. One of the named Yolngu (known to all as Cowboy) is opaque and menacing, and a man called Ricky and a woman called Joanne are each depicted as unhappily thwarted.

Surviving pressure

Watson’s underlying question is: how do people (men in particular) survive pressure? A reader as analytically inclined as White might discern two models of coping in Watson’s tersely humorous, warmly empathetic book.

White and his veteran mates, damaged by their Vietnam experience, reconnect after many troubled years and form a new “platoon” dedicated to making useful things, in a remote place populated by welcoming people. As a “tribe” (Watson’s word), they have no duty to the future – only to each other. In the course of completing finite tasks with material outcomes, they will have companionship for as long as they continue their annual working bees.

The Yolngu “tribe” at Donydji face the more formidable task of preserving tradition while creating a viable future. As a “homeland”, they make claims on a colonising society that seems undecided about how much to help them, and about what “help” honours self-determination.

Among Yolngu, there are competing ideas about how to modernise. Social reproduction cannot be effected without political succession. Experience has taught White that in continuing community, human contingencies weigh more than social rules.

The composition of the Donydji mob has changed over the period of White’s stays. According to his 2018 paper, there are fewer of the Ritharrngu families, none of the Wagilag clans, and more Guyula families (who have successfully asserted their customary right to sit down at Donydji).

“The Guyulas were taking over,” Watson reports, because they produced more children than the founding lineages – and because some traditional owner males married into other communities, or found their aspirations blocked. The tensions of political succession are on loud and violent display at Tom’s funeral, the climax of Watson’s story.

Watson’s closing “Coda” tells us “worn out” White continues to keep in touch with his Donydji friends, sharing their “dogged hope”. What makes hope realistic, Watson says, is “the place itself”.

In Yolngu cosmology, it simply makes no sense for Country to lack people who use it and look after it. The Donydji mob see their future – not just their past – in what they are making there.

Timothy Michael Rowse does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.