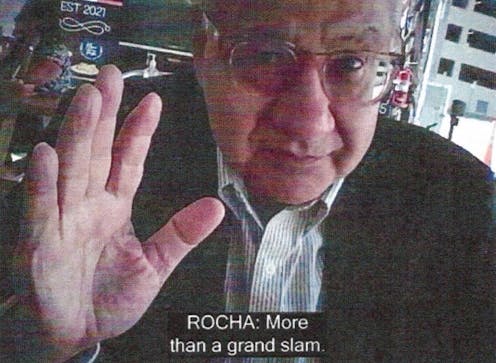

The U.S. Department of Justice announced on Dec. 4, 2023, that Victor Manuel Rocha, a former U.S. government employee, had been arrested and faced federal charges for secretly acting for decades as an agent of the Cuban government. Rocha joined the State Department in 1981 and served for over 20 years, rising to the level of ambassador. After leaving the State Department, he served from 2006-2012 as an adviser to the U.S. Southern Command, a joint U.S. military command that handles operations in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Harvard Kennedy School intelligence and national security scholar Calder Walton, author of “Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West,” provides perspective on what U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland described as “one of the highest-reaching and longest-lasting infiltrations of the United States government by a foreign agent.”

How common is it for spies to embed in foreign governments?

Every state seeks to place spies in this way. That’s the business of human intelligence: providing insights into a foreign government’s secret intentions and capabilities.

What makes Rocha’s case unusual is the length of his alleged espionage on behalf of Cuba: four decades. It’s important to emphasize the word alleged here – the case is underway, and Rocha has not yet offered a defense, let alone been convicted.

If proved, however, Rocha’s espionage would place him among the longest-serving spies in modern times. Allowing him to operate as a spy in the senior echelons of the U.S. government for so long would represent a staggering U.S. security failure.

What can a spy in this kind of position do?

Typically, an embedded spy would be tasked by his or her recruiting intelligence service to take actions like stealing briefing papers, secret memorandums and other materials that show what decision-makers are thinking. Such work quickly resembles movie scenes – photographing secret documents, swapping information in public places or depositing it under lampposts and bridges.

Having an agent reach ambassador level would be a prize for any foreign intelligence service. Rocha held senior diplomatic postings in South America, including Bolivia, Argentina, Honduras, Mexico and the Dominican Republic. This would have given him, and thus his Cuban handlers, access to valuable intelligence about U.S. policy toward South America — and anything else that crossed his desk.

An embedded spy can also act as an “agent of influence” who works secretly to shape policies of the target government from within. This will be something to look for as the federal government discloses more information to support its charges against Rocha.

Presumably the U.S. intelligence community either already has carried out a damange assessment, or is urgently now conducting one, reviewing what secrets Rocha had access to during his diplomatic service – and whether, as ambassador to Bolivia, he may have shaped U.S. policy at the behest of Cuban intelligence.

Has Cuban intelligence partnered with Russia, in the past or now?

Cuban intelligence worked closely with the Soviets during the Cold War. After Fidel Castro took power in Cuba in 1959, Soviet intelligence maintained close personal liaisons with him. Cuba’s intelligence service, the DGI, later known as the DI, received early training and support from the KGB, Russia’s former secret police and intelligence agency.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, Cuban intelligence operatives acted as valuable proxies for the KGB in Latin America and various African countries, particularly Angola and Mozambique. But they didn’t just follow Moscow’s direction.

As Brian Latell, a former U.S. intelligence expert on Latin America, has shown, Castro’s intelligence service was often far more aggressive than the Soviet Union in supporting communist revolutionary movements in developing countries. Indeed, at times, the KGB had to try to rein in Cuban “adventurism.”

One of Cuba’s greatest known espionage feats was recruiting and running a high-flying officer at the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, Ana Montes, who spied for Cuba for 17 years before she was detected and convicted. To the best of my knowledge, there is no publicly avilable U.S. damage assessment of her espionage, but one senior CIA officer told me it was “breathtaking.”

Cuban intelligence recruited Montes while she was a university student and encouraged her to join the Defense Intelligence Agency. There, using a short-wave radio to pass coded messages and encrypted files to handlers, Montes betrayed a massive haul of U.S. secrets, including identities of U.S. intelligence officers and descriptions of U.S. eavesdropping facilities directed against Cuba.

Cuban and Russian intelligence agencies maintained their ties after the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union collapsed. That relationship has only strengthened since Vladimir Putin, an old KGB hand, took power in the Kremlin in 1999.

Putin’s government reopened a massive old Soviet signals intelligence facility in Cuba, near Havana. This facility had been the Soviet Union’s largest foreign signals intelligence station in the world, with aerials and antennae pointed at Florida shores just 100 miles away.

Soviet records reveal that Moscow obtained valuable information from U.S. military bases in Florida. Russia may well still be trying to try to eavesdrop on U.S. targets today from Cuba, although the U.S. government is doubtless alert to such efforts and is likely undertaking countermeasures.

Cuban intelligence today is also collaborating with China, which reportedly plans to open its own eavesdropping station in Cuba. Beijing has significant influence over Cuba as its largest creditor and, following in Soviet footsteps, views the island as a valuable intelligence collection base and a “bridgehead” — the KGB’s old code name for Cuba — for influence in Latin America.

If Rocha is proved guilty, how would he rank historically among other spies?

It remains to be seen what damage Rocha may have done while allegedly working as a Cuban spy. His tenure in the U.S. government, however, would place him right up there with the most successful, and thus damaging, spies in modern history.

The longest-running Soviet foreign intelligence agent in Britain, Melita Norwood, spied for the KGB for four decades. When she was exposed in 1999, the unrepentant 87-year-old great-grandmother was quickly dubbed “the great granny spy” in the British tabloid press.

In the United States, the highest Soviet penetration of the executive branch was probably Lauchlin Currie, who was President Franklin Roosevelt’s White House assistant during World War II. Records obtained after the Soviet Union’s collapse reveal that Currie acted as a Soviet agent.

The greatest damage to U.S. national security, however, was done in the 1980s and 1990s by Aldrich Ames at the CIA and Robert Hanssen at the FBI. Each man betrayed a wealth of secrets, including U.S. intelligence operations. The information that Ames stole for the Soviets led to the arrest and execution of Soviet agents working for U.S. intelligence behind the Iron Curtain.

In due course, we will find out whether Rocha occupies a place of similar ignominy in U.S. history.

Calder Walton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.