The detritus of grief litters a suburban Atlanta home office.

Letters of condolence. File folders stuffed with insurance policies and investment accounts. The contents of a husband’s golf club locker that a 34-year-old widow can’t yet bear to sift through. And resting on a desk, lost in this muddle, a child’s drawing.

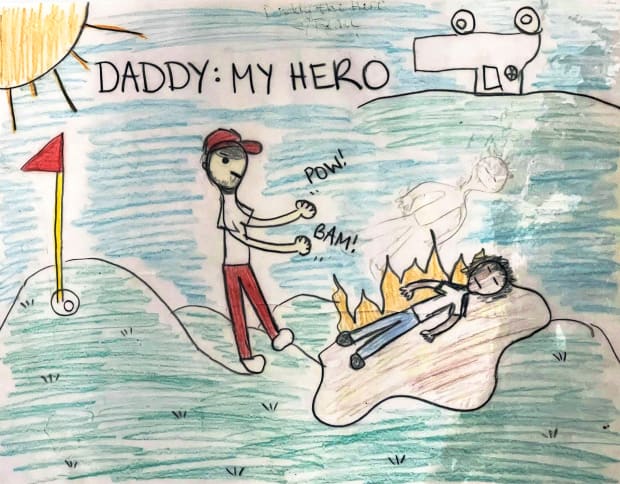

The sketch, on white paper, depicts a bright summer sun and blue sky over a golf course. One man, in red pants, stands triumphantly near a flagstick, having felled another man, prone below him. The victor’s fists are accompanied by comic-like interjections: POW! BAM! There’s an overturned white truck in the background, wheels up.

And above this colorful scene, written in crisp black uppercase letters, is DADDY: MY HERO.

The picture captures not a fiction, really, but a heartbreaking inversion of the truth—the manifestation of a 7-year-old mind probing for order in a world turned upside down. Beau Siller put colored pencil to paper one day after his father, Gene, was shot dead last summer on the 10th green at Pinetree Country Club, in Kennesaw, Ga., under a bright summer sun and a blue sky. Inside the bed of the truck—which existed in real life but hadn’t been overturned, as Beau drew—were the lifeless bodies of two other men, absolute strangers to everyone at Pinetree.

On July 3, 2021, one world spilled into another when the violence of the illegal drug trade pierced the afternoon calm of a golf club and that club’s head PGA professional, 46-year-old Gene Siller, sped toward untold danger. His fate was the tragic terminus of a life spent devoting himself to a family and a sport and a club, of following his heart, of always being the first one to answer a call for help. Even when danger idled 400 yards away.

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

Gene’s path to the 10th green at Pinetree started at Clovernook Country Club, five houses down from his childhood home in northwest Cincinnati. There he spent his early years foraging for golf balls; he knew precisely where to look for errant tee shots, and he delivered them to his grandfather for spare change.

The ones he didn’t pawn off he put into play on imaginary links in his backyard. The sandbox was a bunker. Course architecture demanded wedge shots fly over small trees. And when Gene outgrew the yard he joined his father, also named Gene, for Sunday-morning scrambles. He treasured the lone miniature victor’s trophy they collected.

The game kept Gene busy in his favorite place, the outdoors (where he also spent time working on cars with his father and tended to orphaned rabbits). He won one 11-and-under tournament and played on his high school team—but he was never quite talented enough to earn a college scholarship. His focus turned toward earning a degree in mechanical engineering at Purdue, after which he landed a job in Indianapolis, where he developed five patents related to emergency exit alarms.

His mother, Sharon, saw that first office, though, and was jarred. With its fluorescent lights and no windows, it seemed like a cage for someone who spent so much of his free time on the links—or hiking or rafting or skydiving.

Gene’s favorite escape in these years was a lovely course on Indy’s east side: a Pete Dye design called The Fort, with a surprising number of steep slopes and elevation changes for central Indiana. And slowly that escape became an obsession. He won the club championship, and staffers, noticing his talent and even temperament, asked him to start instructing junior golfers.

Which is how he latched on in 2003 as an assistant pro, giving up a steady, well-paying job for the chance to work long hours, for little pay, in the heat and cold and rain. Well-suited for complex problem-solving, Siller would employ this skill in, say, running a flawlessly organized tournament, or teaching young golfers how to flush their irons. “You don’t want to sit back and in 20 years [wonder]: Boy, could I have made it as a golf pro?” his father told him approvingly.

Soon the sport lured Siller south, toward Atlanta, where courses stayed open nearly year-round. He took a similar job at St. Ives Country Club in 2007, and it was in this role that he ended up attending the type of expo where camps and sports programs peddle their summer services to local moms and dads. Gene was promoting golf clinics at St. Ives. Ashley Bouknight, a student at Georgia, was touting cheerleading camps. Had their booths been set up a bit farther apart, perhaps they never would have chatted. But as the hours wore on, they grew more focused on each other.

He wore penny loafers and a white cashmere sweater on their first date; she looked past his fashion choices and found warmth. They drank and laughed, and later Ashley told her best friend that Gene was special. Two weeks later, she promised herself she would someday marry him. And two years after that, she did. Beau arrived in 2014. A younger brother, Banks, followed in ’15.

Courtesy of the Siller family (2)

Early on, when they were dating, Gene left Ashley a Post-it with a sweet message. When she told him how much she appreciated it, notes started to appear all over. And the passage of time did nothing to cool those affections—Ashley remembers how they always sat close on the sofa, a hand on the other’s leg, to the end.

For Gene, that love superseded even his own ambitions. Ashley had family peppered around metro Atlanta, and he promised her they’d always stay nearby, even if that limited his pool of potential employers as he worked toward becoming a head PGA pro. He got that chance at another local club, but it proved to be an 80-hours-a-week slog that pulled him away from his sons and put an unfair burden on Ashley, who had her own career. Gene left that job after the club changed owners, and he found himself mostly tending to the yard and dropping the boys off at school.

Then, one day in the summer of 2019, he fielded a call: Pinetree Country Club was hunting for a new head golf pro.

The man on the line was Pinetree’s general manager, Brad Nycum, a former Florida State golf teammate of Paul Azinger’s. His course wasn’t exactly heralded, but golf was central to the experience: Opened in 1962, it was known for immaculate greens that ran true. Arnold Palmer and Bobby Jones had played a round there, and it was once the home course of Larry Nelson, a three-time major winner.

Satisfying as Gene found his new role of full-time dad, there was a new void—he missed arriving every morning to an office that smelled of freshly cut grass; he missed using his engineer’s mind to help a place such as Pinetree operate at peak efficiency. Ashley wasn’t surprised when her husband found Nycum’s offer appealing. “Gene was always so unwavering in his decisions,” she says. “He knew who he was: This is what I’m passionate about. I can live my life being really happy doing what I love.”

And so Gene let love guide him to Pinetree. He inherited a staff of three and he led by example. He cleaned the carts and filled their sand bottles to precise levels. He patrolled the course, picking up broken tees and cigarette butts. He brought a snazzy, new aesthetic to a staid, old pro shop, stocking it with the type of vibrant Puma gear he favored. And he catered to Pinetree’s female members, who’d long felt ignored at an old-boys club. He started organizing women’s tournaments and ramping up their offerings at the pro shop.

With less demanding hours, the new job afforded Gene enviable flexibility: time to see the boys off to school in the mornings, to play golf with them on Sundays, to tend to household projects on Mondays. The Pinetree job, Ashley says, “made our marriage beautiful.”

God, life is so good,” Ashley told Gene on July 2 from the passenger seat of their black Silverado as they drove home from the beach house in South Carolina that they’d shared for a week with a dozen family members. Gene had landed his dream job; Ashley was thriving in corporate sales at AT&T. The boys, strapped in the back, were healthy and their personalities were beginning to show—Beau gregarious, like Ashley; Banks methodical, like Gene.

Technically, Gene was still on vacation, but Pinetree was scheduled to hold its annual Fourth of July celebration the next day—the club’s biggest event of the year—and as they drove home he felt the tug to go lend a hand in the morning. “I really want to check on my team,” he told Ashley, who asked only that he be back in time to watch fireworks with the kids. “Just to make sure they don’t need me.”

Ashley was perched again in a passenger seat the following afternoon. This time, though, her father, Ron Bouknight, drove as they barreled west, tracing Gene’s hourlong commute to work. This time, Ashley reflected not on all that she had, but on all she might have lost.

Rumors were swirling. Concerned phone calls were made. And all of it propelled Ashley toward Pinetree in a panic. Something went wrong. There was a shooting. Gene’s been hurt. Now Ashley was calling her husband again and again, and he never answered.

If there was an active shooter, she thought desperately, maybe Gene was hiding and couldn’t pick up. Maybe he was busy keeping other people safe. There was still hope, she felt, when at 4:49 p.m. she sent her husband a pleading text: Please answer. . . . Please, please text me that you’re O.K. If you see this, I love you more than you know, Genie.

Ashley called the pro shop, the tennis shop, the kind nurse who played at the club and whom she’d once met at a function—and the phones rang endlessly. Finally, digging through old emails, she found Nycum’s number. At last, a voice on the other end.

“What do you know?” Nycum asked.

“I know Gene has been shot.”

“What else do you know?”

“That’s all.”

Silence.

“Is he alive?” Ashley pleaded. “Is he alive?”

“No,” Nycum mustered. “I’m so sorry.”

Arriving at Pinetree, Ashley demanded to see Gene. She wanted to sprint past the police who’d arrived, to see for herself that Nycum was wrong, but she was intercepted by a club member, Loretta Byrne, who witnessed the damage wrought by two bullets, and who begged Ashley, over and over, to spare herself the image. “That [would have been] a picture she wouldn’t be able to get out,” Byrne says.

Eventually Ashley was permitted to walk to the back of Pinetree’s expansive clubhouse, where she settled atop A-frame steps that afforded a view of the driving range and, to the left, the crime scene in the distance.

The par-4 10th hole is a slight dogleg left. The right side of the green is guarded by a large pond and a pair of bunkers. Ashley could see that one of those bunkers had trapped a massive white pickup, left teetering on the edge. Beyond that, the tableau was tough to read, save for one unmistakable detail, visible even hundreds of yards away: the bright-red pants that Gene had been wearing that morning as he bounded downstairs. He’d looked so damn handsome, she remembers thinking as she kissed him goodbye.

Gene was ebullient as he strolled up to Pinetree at 9 that morning, his red pants matched with an American flag golf shirt. The place buzzed with life: families packing the Olympic-sized swimming pool, workers assembling tables for a dinner buffet. Inside the pro shop, Gene bumped into 32-year-old Tanner Farr and asked the assistant pro about his progress in the PGA management program. Farr had just moved up a level, and Gene offered some encouragement. “Stay at it.”

A few hours later, another assistant, 25-year-old Harrison Bryant, punched in to man the golf shop. And it was Bryant, through the window behind the register, who first spotted the white Ram 3500 near the 10th green. This was at 2 p.m.; he assumed the fireworks crew had come early to set up. But when he glanced back again, after a few phone calls, he was surprised to see the same vehicle—and now it was caught on the lip of the front bunker.

Bryant mentioned this to Gene, who grabbed a cart and headed straight off. Siller had grown accustomed to chasing teenagers and fishermen from the course; or perhaps, in this case, someone needed help. He was just doing his job when Bryant, through binoculars in the pro shop, saw him pull up to the truck and appear to engage with the driver.

It all happened in the time it takes to field a call. The phone rang again. Bryant answered. He hung up, turned back, and from afar saw Gene sprawled on the ground. There was a surge of audible horror from the members on the driving range—and then someone sprinted into the shop, screaming for Bryant to call 911.

Byrne, the club member, had just ordered lunch in the small restaurant abutting Pinetree’s pro shop when she saw the truck moored on the bunker and heard the shouts from the range: The members there heard five or six gunshots, saw Gene fall and watched a man sprint into the course’s dense woods. A nurse by profession, Byrne scrambled to a golf cart and rushed toward the scene, where she found Gene motionless, the white truck’s engine still rumbling. She helped roll Siller’s body over and observed that he’d been shot through the neck and the back of the head. Blood pooled beneath him. He gave no pulse, no signs of life—but still, she and another golfer took turns administering CPR.

Only when a dozen police cars roared up to the scene did the futile compressions finally cease. Byrne, in the commotion, had left her phone in the golf cart, and there it would remain for hours, buzzing in her purse, as the caller sped toward Pinetree.

Courtesy of the Siller family

Police activated a manhunt for an attacker wearing a white shirt and dark work pants. Bryant, back at the pro shop, wondered despondently whether he should’ve made the trip to 10 himself. And Nycum helped cobble together a note, calling off the fireworks.

Amid the chaos, the GM stepped outside for a quiet moment—but he was quickly interrupted by a call. On the other end he heard a desperate woman’s voice.

The night of the shooting, Ashley retreated to the bottom bunk in a bedroom at her mother’s home that was reserved for visiting grandkids. The bed is adorned with a navy-blue comforter; the boys’ names are stitched into the pillows. Like a cave, it insulated Ashley from the horrors of the new life that loomed outside. But she knew she would have to break that barrier.

The next day, she brought in the boys, still ignorant to their father’s fate, and sat ashen-faced on the edge of the lower mattress—Beau on her lap, Banks in front of her. She had spoken to a child psychologist about how to break the news without breaking her children. Be truthful. Be direct. Don’t lie. Speak their language.

The boys asked Mommy whether she was O.K. She told them she wasn’t, that they needed to listen to her, that what she was going to tell them would be very hard to hear, but that she would answer their questions when she was finished.

Throats tightened. The air thickened.

Then she told them that Daddy—their hero; the one who showed them how to swing a golf club; who they ran to hug as soon as he walked through the door every evening—was gone, and he was never coming back.

Banks wore a blank stare as he tried to process his mother’s words. Over the coming days he would ask again and again when his dad might be home, or he’d sit with his iPad, a picture of Gene on the screen, staring in silence for long stretches. “I just want to look at his face,” he would say.

Beau, on the bed, burst into tears. Immediately he started asking about the bad guy. Who is he? Will they catch him? He cuddled up to Ashley, who told her boys it was the police’s job to find the killer, and that it was everyone else’s job to remember Daddy. To think about him often. To share happy stories. To cry whenever you need.

In August, Pinetree hosted the Gene Siller Red Pants Memorial tournament, which raised more than $250,000 for a grant, created by Ashley and named after her late husband, targeted at young golfers. The goal, Ashley says, is to honor the joy that Gene took in teaching junior players, including their two little boys. Bryson DeChambeau, Rickie Fowler and Jordan Spieth donated golf bags for an auction, and there was an array of items up for bid autographed by the likes of Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods.

Out on the course that day, 61-year-old Billy Jack split the fairway on the 10th hole. As he stood over his second shot, pin guarded by the pond and those two bunkers, he couldn’t take his mind off what had happened on the green ahead to his old friend, and he skulled his approach into the front trap.

Another longtime golf buddy, 48-year-old Ryan Joyce, on this afternoon had the honor of using Siller’s clubs. Gene and Ryan had partnered up in dozens of tournaments; they never quite won one, but Joyce always appreciated Siller’s composure as he engineered his way around a course. Now Joyce freezes up every time he stands at a 10th-tee box, no matter the locale. Since his friend’s death, he plays sparingly.

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

The tire tracks on the 10th green at Pinetree are gone. Groundskeepers long ago repaired the torn-up turf and mended the damaged bunker and flooded the area where Siller fell with water and soap tablets, again and again, until his blood was soaked into the soil. But still his memory remains ingrained on the course. Byrne, for one, can’t shake the image of his mangled face. Other members are taking self-defense classes and learning to use firearms. “I’ll think about it the rest of my days here,” says Dianne McPherson, who accompanied Byrne to the crime scene and for weeks afterward couldn’t bring herself to play the 10th hole.

That sort of pain, though, may be most profound among those who loved Siller the longest. “You live all your life, you count your blessings and you think how good your life has been,” says his father, Gene. “Then this happens, and you really question things.”

Sharon Siller aches when she thinks about how her son died, how frightened he must have been. The depth of her love matches the depth of her grief. Her daughters worry that she and her husband, both now over 75, are irreparably damaged. They routinely turn down lunch invitations from friends, avoiding uncomfortable questions. Some days Sharon will seem particularly morose, and Gene will have to cajole her out of the sorrow. The next day, the roles reverse.

Then there’s Ashley. Occasionally, these days, she ventures into her walk-in closet and collapses near her dead husband’s hanging array of bright golf shirts and slacks, wrapping her arms around them as she sobs, clinging to little bits of fabric. Really, she is hanging on to the image that she wants to savor, of the man who strolled downstairs each morning in a bold outfit that matched the pride he took in his work, who conveyed contentment in the path he’d chosen. She’ll nuzzle the clothes and shut her eyes and will herself to remember that Gene.

Sometimes, though, she pictures the other Gene. The one who was so poorly pieced together that she thought she’d wandered into the wrong room at the funeral home on July 9. Gene, always cautious, used to tell his wife that if she ever found herself in danger, and he wasn’t there, she should turn and run. Gazing later at his cold body, Ashley realized that a chunk of his right thumb had been sewn back on; she figures that in his last moments he had turned to run, holding up a hand to shield himself. Sometimes she can’t stop herself from thinking about that Gene.

She tries instead to remember their talks, late into the night, at the pirate-themed bar her husband years ago built in their basement. Now, she returns only occasionally to “Gene and Ashley’s Arrrggg Bar,” but her favorite place in the world feels empty. More often she finds herself in that cluttered home office, with the piles of paperwork, a widow’s endless checklist. There she makes call after call, from a script achingly familiar to anyone who’s ever carried the burden of loss: Hi, my name is Ashley Siller. My husband, Gene, recently passed away . . .

She’s grown accustomed to forcing a smile. At board meetings for the grant, and at public events such as the tournament, she hides behind the polished façade of a corporate sales rep. In photos from a fall vacation to Disney World—a trip she planned with Gene before he died—she’s beaming. Those smiles, though, exact a toll when she returns to an empty home and peers out from behind the mask. “I’m totally a disaster,” she says. “I’m really, really broken.”

Courtesy of the Siller Family

In trauma therapy she learned that when Gene died her amygdala flooded her brain with stress chemicals, making it difficult to think linearly or solve problems. She finds herself perpetually caught between the present moment and the trauma of July 3, as if it has all been one relentless day. Her mind drifts when she tells stories. She still refers to Gene as if he’s alive.

She even thinks about her husband in the present tense. During his time at Pinetree, Gene always made it home for dinner. Now, as Ashley cooks supper and the clock creeps toward 7 p.m., she still waits for the side door to swing open. For her boys to dash to their impeccably dressed father. For Gene to fill the room with the warmth that’s gone missing. Her eyes shift from the clock to the door, the clock to the door. But it never opens.

Amid such melancholy, she holds tight to small comforts. Like: Ashley’s therapist told her, to great relief, that the foundations of character are cemented in a child’s first seven years, give or take. Ashley is confident that Gene will live on within Beau and Banks—his steadiness, his itch to enrich the lives of others. She particularly sees her husband in Banks, who’s prone to quiet analysis before a decision. Once, though, he had a bedtime meltdown, and Ashley burst into tears. “I’m trying the best I can right now,” she pleaded.

“Banks, be nice to Mommy,” Beau said, sensing the moment’s Gene-sized void.

The boys ask often about the man who killed their father, worried about their safety. Ashley tiptoes, too; she hired private security in the days after Gene’s death. Her heart races whenever she sees a white pickup truck. And every night she takes an extra lap around the house, checking doors and the alarm, household chores that Gene used to tackle, that she says she took for granted. She feels her husband’s absence most in those realizations: She had little sense of how much time he spent tending to their yard until, a month after his death, bushes, vines and grass had sprung forward, unchecked.

For these extra burdens—for being robbed of her best friend, for feeling exhausted after another day of single parenting—anger occasionally subsumes Ashley’s grief. Her fury is directed at the accused shooter, then 23-year-old Bryan Rhoden, a former metro Atlanta high school football player who’s had a string of drug-related run-ins with law enforcement across his young life.

According to prosecutors, Rhoden (who sits on trial in Cobb County, where he pleaded not guilty) and an accomplice, Justin Caleb Pruitt (who, records suggest, remains at large), kidnapped both Paul Pierson, 76; and Henry Valdez, 46; and used duct tape to bind their arms and legs, the violence seemingly tied to all four men’s purported connections to the drug trade. After stuffing Pierson and Valdez into the bed of Pierson’s truck, Rhoden and Pruitt allegedly drove some 40 miles to a dead-end street bisected by the cart path leading from Pinetree’s 10th green to its 11th tee. There Rhoden allegedly shot Pierson in the torso and Valdez in the head, and the truck appeared headed for a discreet disposal in the lake guarding Pinetree’s 10th green . . . until the bunker intervened, stranding the truck and prompting Gene to set off up the fairway. Siller was merely a victim of happenstance, stumbling upon an atrocity he was never intended to see.

“I don’t hate anybody,” Ashley says. But “I loathe [Rhoden] with every ounce of my soul.”

Ashley stifles that hate by clinging to what she loved. On the day before Gene’s funeral, she and three girlfriends ventured to Pinetree’s 10th-hole green, where a collection of flowers, photos and golf balls marked the spot where Siller had fallen. Ashley brought along two pictures her boys had drawn, including Beau’s bright summer sun and blue sky, and she leaned down to place them on the turf when a mammoth dragonfly landed on the red pants Beau had sketched. The women fell silent. The insect hopped over to the other drawing, by Banks, then fluttered back to the red pants for a few seconds more before flying away.

Across cultures and religions, the dragonfly is a symbol of rebirth, and Ashley has convinced herself that Gene buzzed by to say hello—to show that he was with her, always. Like Gene’s path to Pinetree, and to the 10th hole, one could see the dragonfly as fate. Or just a coincidence. In her sorrow, Ashley chooses fate.

Courtesy of the Siller family

Now, she and those around her see dragonflies everywhere. Her mother spied one hovering over a vine wrapped around the staircase of Ashley’s back deck, a gardening flourish that Gene treasured. Byrne describes how one hung nearby while she was on the phone with Ashley. And when family members took Banks to play at Joyce’s course, Hawks Ridge, a dragonfly followed them for nine holes. That night, Banks reported to Ashley’s mother, “Nana, Daddy watched me play.”

Joyce knows: When you’re looking for something, you’re bound to see it. Also, dragonflies are ubiquitous in muggy Georgia summers. They perceive color more vibrantly than any other creature; perhaps Ashley’s visitor at Pinetree was simply attracted to the splash of red in Beau’s drawing.

For those closest to Gene, though, these explanations are inconsequential. Probing for meaning amid misery, they attached his name to dragonflies, omnipresent in gardens and golf courses, his favorite places.

The most important decisions in Gene Siller’s life were governed by his devotions—right up until the end. Now, to repay him, the people he loved will do all they can to ensure that his two little boys never stop noticing the dragonflies all around them.