Childhood trauma is a global health problem. Every year, up to 1 billion children worldwide experience some form of emotional, physical or sexual abuse. More than two-thirds of children report at least one traumatic event by age 16.

Without early intervention, these experiences may deeply infiltrate the minds of children, who may reenact their original trauma by entering toxic relationships that repeat the dynamics of parental abuse. Or they might engage in high-risk behaviors, including unsafe sexual relationships, delinquency or substance abuse.

Childhood trauma can lead to guilt, shame, anxiety, depression and even suicide. Its effects often last well beyond childhood and affect physical and mental health into adulthood.

I am a clinical psychologist and director of training at the nonprofit Lifeline for Kids, a center for childhood trauma at UMass Chan Medical School. I have been participating in a project that treats Ukrainian children and families affected by the war since March 2022.

The project is being carried out by German researchers in collaboration with several organizations. Through this program – called Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Ukraine – I provide online training and consultation calls to the Ukrainian therapists who are treating children who have been directly affected.

This experience has impressed upon me the great importance of the power of intervening directly during ongoing trauma and early enough in a person’s life to help heal the wounds of complex adversities.

The Ukraine project

During the first tragic months of the war, my job was to educate therapists about this form of treatment so that they could counsel the war-impacted children and their families.

Given that they were still exposed to an ongoing threat in Ukraine, it was critical to help the children differentiate between a real danger and what was only a reminder of their trauma. So the therapist would teach them relaxation skills to manage the stress from hearing sirens or being evacuated to a new location.

Our team of international trainers also addressed secondary trauma – in this case, the traumatic stress that mental health care providers are experiencing.

Initial results show that more than 130 clinicians were trained in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. In turn, they collected data from more than 140 children and caregivers. The therapists rated their overall satisfaction with the training as high.

A different brain architecture

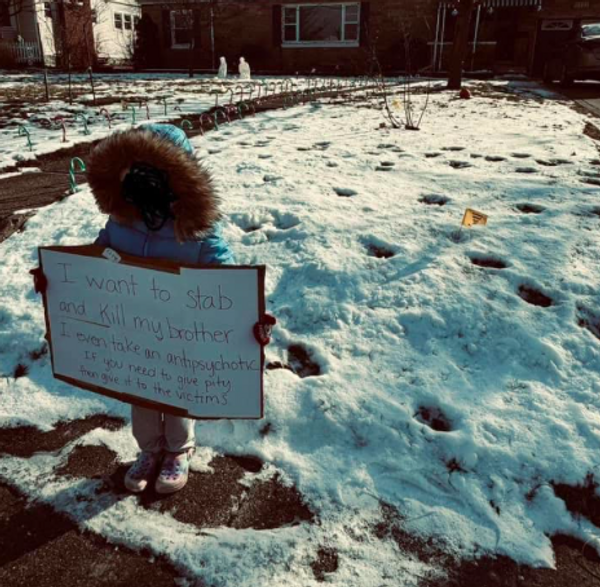

Although events like wars, pandemics and school violence are some of the most obvious reasons for trauma, approximately three-quarters of reported cases of child abuse – such as sexual abuse – are committed by family members or other people who are part of the victim’s “circle of trust.”

Children experiencing complex trauma – whether parental abuse or the crossfire of war – develop a biology that is very different from their nontraumatized peers. Studies show that trauma leaves marks not only on the brain but also on other parts of the body.

Chronic stress leads to ongoing activation of the stress response system, which activates neural connections involved in fear, anxiety and impulsive reactions.

Even in the absence of a real threat, the fight-flight-freeze response – located in the amygdala, or the primitive, instinctual and survival-oriented part of the brain – remains constantly activated. Something as simple as a change in someone’s facial expression can activate the fear circuits.

The chronic stress response leads to the release of the hormones cortisol and adrenaline, which then has downstream effects on other systems. This can lead to suppression of the immune system and small shifts in how a person’s underlying genetics respond to their environment. In addition, other brain regions that are less important for survival – such as problem-solving, learning and memorizing – are less developed in children who have experienced trauma.

But there can be another, more positive reaction to stress, which involves asking for help and support from safe people. That’s why the presence of supportive adults, along with acquisition of new coping skills, can blunt the impact of trauma. Ultimately, it is the buffering, not the suffering, that determines how a child reacts to trauma.

Children are resilient. With appropriate treatment and support from caregivers and professionals, they can heal and thrive.

Storytelling as a means of healing

Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective for many mental health conditions. It is a form of talk therapy based on the understanding that psychological problems come from unhelpful or inaccurate ways of thinking; these thoughts then affect our emotions and behaviors.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy differs in several ways. First, it helps the child recognize how past trauma affects their view of themselves and their behavior. For example, a female adolescent who was sexually abused may be triggered by a male friend who comes physically close to her.

The therapy also uses a well-established technique called trauma narration. Here, the child narrates the traumatic experiences that happened to them. It can be spoken, written or expressed in a drawing, poem or song.

With the therapist’s help, the child identifies the distorted thoughts that negatively affect their views of themselves, others and the future: “It was my fault that I was sexually abused; I cannot trust anyone; I will be broken forever.”

The therapist then helps the child shift their perspective and incorporate the trauma in their life story in a way that is no longer overwhelming, harmful and shameful.

When this happens, trauma-related symptoms such as hypervigilance, repetitive thoughts and avoidance significantly decrease. Instead of seeing themselves as broken, damaged and unlovable, these children recognize their resiliency and strength.

One example: An 8-year-old boy who saw his mother die from cancer was having severe nightmares. The thought of sickness or death terrified him. He was refusing to go outside his home, was emotionally withdrawn and didn’t want to see friends.

But after receiving trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, he could express his emotions over his mother’s death. He was no longer afraid at night and his nightmares decreased. He formed new friendships.

The therapy typically requires from eight to 25 sessions, depending on the number of traumatic experiences and the complexity of the symptoms.

Caregivers are critical

The No. 1 factor for healing from trauma is the presence of a safe, nurturing and predictable caregiver – a parent, grandparent, social worker, pastor or coach.

One of the most powerful moments in treatment is when the child – with the support of the therapist – shares the narrative with the caregiver or another significant adult in the child’s life. These sessions give an opportunity for the caregiver to praise the child and acknowledge the strength it took to create and share their narrative.

Clinical studies have shown that trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy works for children and young adults from ages 3 to 21 across all geographic, ethnic, gender, religious and socioeconomic settings. It works for a Ukrainian teenager victimized by war – or for an abused child living in a U.S. suburb.

Studies on this form of psychotherapy consistently show that patients have less anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder than patients who have undergone other forms of treatment. Children become more resilient and the benefits of therapy last longer.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy helps children change their story from a broken one to a heroic one.

As a 16-year-old girl told me: “This therapy has completely changed my life for better. I now wake up everyday without having this weight of shame and depression hanging on me. I can finally live my life without feeling like I’m going to break down at any second.”

Zlatina Kostova does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.