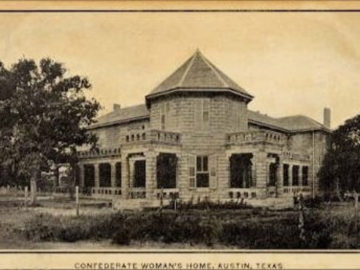

In 1908, the Texas chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy built a 15-bedroom mansion in Austin’s leafy Hyde Park neighborhood, a mile north of the University of Texas. Intended to house elderly wives and widows of Confederate veterans, the Confederate Woman’s Home, like similar facilities in other southern states, was part of the Daughters’ mission to create “living monuments” to the Confederacy, an effort that also involved erecting hundreds of Confederate memorials across the South in the early decades of the 20th century.

The Confederate Woman’s Home still sits at 3710 Cedar Street, and last summer demonstrators enraged by the murder of George Floyd convened at its doorstep. One protester covered the site’s state historical marker with a sign that read, in part, “the glorification of a white supremacist group is an insult to our BIPOC neighbors.” The building’s current owner, AGE of Central Texas, a nonprofit that provides education to caregivers and the elderly, appeared to get the message. On June 23 it covered the marker with a black plastic bag and attached a notice declaring the organization’s commitment to equal rights.

This gesture of solidarity ignited a battle—over the status of Confederate markers and monuments, over local control, and over private property rights—that has played out over the past year in virtual meetings of the Texas Historical Commission, the state agency charged with historic preservation. In response to this incident and other efforts to remove Confederate memorials across the state, the commission has strengthened protections for Texas historical markers and enacted a new rule requiring a majority vote of the 15-person commission before a state antiquities landmark can be “retired.”

Critics charge that such moves are intended to make it more difficult to remove Confederate memorials. The Confederate Woman’s Home marker was approved by the Texas Historical Commission in 2012 and erected with permission from AGE. This summer, AGE requested its removal, which the commission unanimously denied at its October meeting; a request by the organization to rescind the building’s landmark status is currently under review. At the same meeting, the commission also rejected a request by the mayor of Lancaster, a small town south of Dallas, to remove a historical marker for a former Confederate arms factory.

According to commission spokesperson Chris Florance, the commision has never approved a Confederate marker removal, and has permitted the removal of only one Confederate memorial. In July, it allowed Denton County to remove a statue of a Confederate soldier from the grounds of its courthouse—but only if the county eventually puts the statue back on display in some other location. (Only monuments on state property and official markers on private land fall under Texas Historical Commission jurisdiction.)

Florance says the new regulations merely establish a process for removing memorials. No process had previously been necessary, he explained, because until recently, the commission had received few such requests. “Certainly we’ve heard requests that have pertained to Confederate history. Some property owners simply don’t want the marker on their property anymore,” Florance says.

State representative Shawn Thierry, a Houston Democrat, criticized the commission’s new rules, saying she was “against any policies that are going to make it more difficult to remove monuments statewide.” Thierry is co-sponsoring a bill this legislative session to abolish Confederate Heroes Day, an official state holiday. “It’s time for Texas to turn the page on the Confederacy,” she says. “The time is really overdue to correct the record, to tell the truth of their treason and bigotry.”

The campaign to remove Confederate symbols and monuments from public life began in 2015, in reaction to white supremacist Dylann Roof’s massacre of nine African American church worshippers in Charleston, South Carolina, and intensified after the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Over the past six years Texas officials have removed more Confederate symbols, names, and markers than any other state, including a particularly egregious plaque in the Capitol, placed in 1959, denying that slavery was the cause of the Civil War. But as of 2019, 68 statues remain, most of them erected between 1900 and 1960 as part of a coordinated propaganda campaign, when groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy were actively fighting against equal rights for African Americans. In addition to celebrating Confederate Heroes Day, Texas officially designates April Confederate History Month.

Karen Cox, a historian at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, is the author of Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Cox says the new Texas Historical Commission rules should be seen in the context of efforts by Republican-controlled legislatures and state historical commissions across the South to save Confederate monuments—a reaction to recent Black Lives Matter protests. “These are just textbook GOP tactics,” she says. “This is happening everywhere, and it’s done through these historical commissions, which are made up of political appointees.”

The Texas Historical Commission’s 15 members, who are appointed by the governor to staggered six-year terms, appear divided on what to do with memorials to the state’s Confederate past. Former state Supreme Court chief justice Wallace Jefferson, the commission’s sole African American, has expressed support for removing Confederate monuments, especially from courthouse grounds, while Lilia Garcia, the only Latinx commissioner, is hesitant. “It is very hard to start removing things, because what’s going to happen is you forget the history,” Garcia said at the commission’s October meeting. “We may not like the history, we may abhor it—and we should—but it happened.”

The fact that 13 of the commissioners are white in a state where non-Hispanic whites make up just 41 percent of the population is itself a problem for some lawmakers and activists. “That’s not representative,” says state representative Jarvis Johnson, a Democrat from Houston and another sponsor of the bill to abolish Confederate Heroes Day. “So you’re stacking the deck by saying that in order to [remove a marker] you need a majority vote.”

Liz Peterson, the assistant director of the Houston Coalition Against Hate and a board member of the Convict Leasing and Labor Project, describes the new rules as a power grab by the Texas Historical Commission. “I think it’s a real problem that control over these decisions is being taken from the local citizens and put in the hands of governor-appointed historical commissioners,” Peterson says. “It seems to fly in the face of everything Republicans talk about in terms of local control and private ownership.”

Some commission members appear to be sensitive to such criticism. “I am very conflicted on this particular issue, because I do believe that a private landowner should have the right to decide what’s on their property,” said commissioner Monica Burdette in October, during a discussion over whether to remove the Confederate Woman’s Home marker. “If they don’t want something on their property, it shouldn’t be forced on them.”

Ultimately, however, Burdette joined the rest of the commission in unanimously voting to keep the marker at its present location—even after receiving a letter from AGE Executive Director Suzanne Anderson pleading for its removal. “[The marker] has been a bone of contention with the community as soon as it was posted,” Anderson wrote. “We would very much like to have this marker removed as it distracts from the wonderful work that happens every day within the walls of the AGE building.”

Commissioners seemed more swayed by the arguments of Steve Lucas, CEO of the Descendants of Confederate Veterans, a Texas-based group dedicated to telling “the true history of the Confederate states.” Lucas was the driving force behind placing the Confederate Woman’s Home marker. “The marker was placed with the enthusiastic support and full cooperation of the AGE staff and board of directors,” Lucas told the commission in October. “Now they have made it their personal billboard, jumping on the cancel culture bandwagon.” Lucas received backing from the Travis County Historical Commission, which voted to keep the marker in place. “It’s not a marker about the Confederacy,” County Chairman Bob Ward told the commission. “It’s about women and health care.”

The chairman of the Texas Historical Commission is John Nau, the CEO of Silver Eagle Distributors, the nation’s largest Anheuser-Busch distributor, and a major Republican donor. At the October meeting, Nau expressed concern about removing markers simply “because somebody doesn’t like their content.” He was particularly irritated by AGE placing a black bag over its marker without first seeking permission from the commission. “That seems to me a bit childish on their part,” Nau said, “but you can’t make somebody behave like an adult all the time.” Other commissioners questioned whether covering up the marker constituted vandalism of state property, and whether they could fine AGE. The entire conflict, Nau said, illustrated the need for “a complete approach to protecting markers.”

Activists trying to take down Confederate memorials are often accused of erasing the past. But Cox, the historian and author, contends it was groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy that wanted to replace the ugly reality of slavery and secession with gauzy visions of a noble Lost Cause. Removing monuments that idealize the Confederacy, Cox says, should be seen as part of the effort to tell the real history of Texas. “The history of the Confederate Woman’s Home is always going to be there,” she says. “There are newspaper stories about it, there are pamphlets about it, and there are books about it. Removing the marker does not mean removing the history.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

ERCOT Increased Revenue and Executive Pay In Years Before Texas Power Outages: Top ERCOT officials collected six-figure salaries while failing to prepare for extreme weather events that they were warned about.

-

The ‘Culture of Violence’ Inside Austin’s Police Academy: Recent audits of the city’s cadet training spotlight a warrior-cop culture that pervades policing, even in a so-called progressive city.

-

How the Winter Storm Exacerbated Problems in Texas Lock-Ups: After the near-total collapse of the state’s electric grid, many jails and prisons lacked heat and running water.