Using a telescope perched on a mountain in Arizona, scientists have managed to take snapshots of Jupiter's active moon Io — and these images are so detailed they even rival pictures of the world taken from space.

To capture these views, the team used a camera, dubbed SHARK-VIS, that was recently installed on the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) located on Arizona's Mt. Graham; the new images outline features on Io's surface as small as 50 miles (80 kilometers) wide — a resolution that was, until now, possible only with spacecraft studying Jupiter. "This is equivalent to taking a picture of a dime-sized object from 100 miles (161 kilometers) away," according to a statement by the University of Arizona, which manages the telescope.

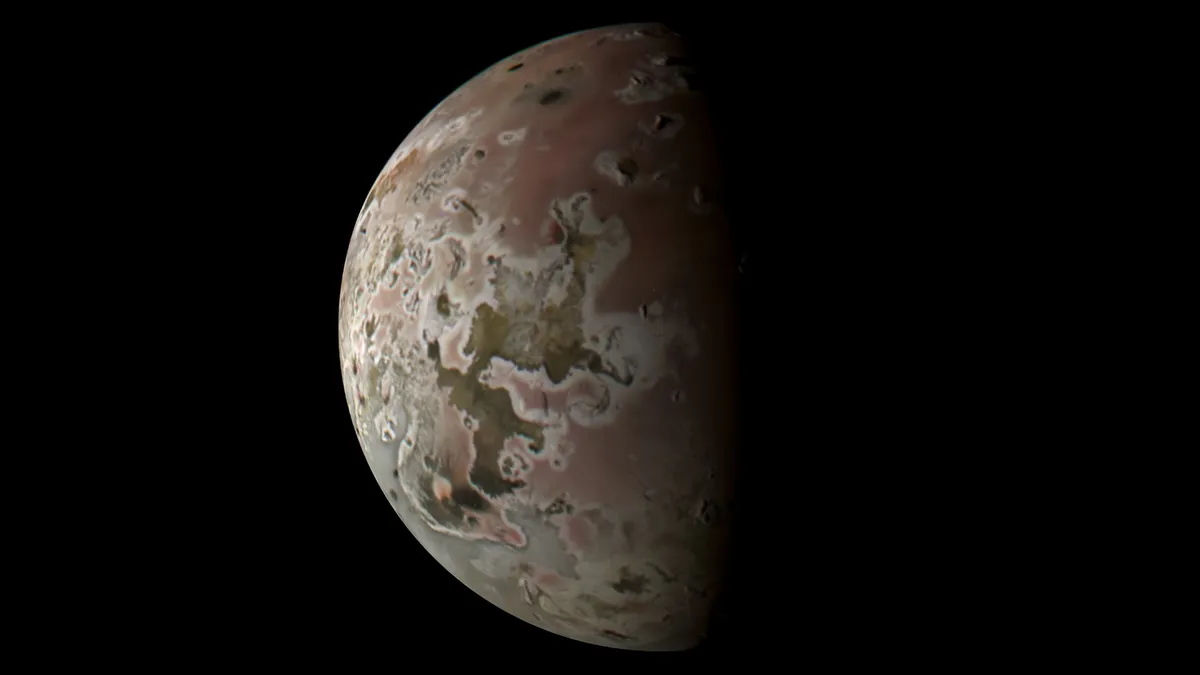

The new pictures of Io are, in fact, so intricate that scientists could discern overlapping deposits of lava spewed by two active volcanoes just south of the moon's equator. An LBT image of Io taken in early January shows a dark red ring of sulfur around Pele, which is a prominent volcano routinely spewing Alaska-size plumes up to 186 miles (300 kilometers) above Io's surface. That ring appears partly obscured by white debris (representing frozen sulfur dioxide) from a neighboring volcano named Pillan Patera, which is known to erupt less frequently. By April, Pele's red ring is once again seen nearly complete in images taken by NASA's spacecraft Juno during its closest flyby past the moon in two decades, revealing a fresh dump of erupted material by the active volcano.

Related: NASA reveals 'glass-smooth lake of cooling lava' on surface of Jupiter's moon Io

"It's kind of a competition between the Pillan eruption and the Pele eruption, how much and how fast each deposits," study co-author Imke de Pater of the University of California, Berkeley, said in another statement. "As soon as Pillan completely stops, then it will be covered up again by Pele's red deposits."

Io's volcanic eruptions, including those by Pele and Pillan Patera, are driven by frictional heat created deep within the moon as a result of a gravitational tug-of-war between Jupiter and its two other nearby moons Europa and Ganymede. Monitoring Io's volcanic activity, which have likely pockmarked the world for most (if not all) of its 4.57 billion years of existence, can help scientists learn about how the eruptions shaped the moon's surface as a whole.

Surface changes on Io, which is actually the most volcanically active body in the solar system, have been recorded ever since the Voyager spacecraft first spotted volcanic activity on the moon in 1979. A similar sequence of eruption from Pele and Pillan Patera was also observed by NASA's Galileo spacecraft during its tour of the Jupiter system between 1995 and 2003.

However, prior to the installation of the new camera on the LBT last year, "such resurfacing events were impossible to observe from Earth," study co-author Ashley Davies, a principal scientist for planetary geosciences at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement. That's because while infrared images from ground-based telescopes can sniff out hotspots pointing to ongoing volcanic eruptions, their resolution isn't sufficient to identify the precise locations of eruptions and surface changes like fresh plume deposits, scientists say.

"Although this type of resurfacing event may be common on Io, few have been detected due to the rarity of spacecraft visits and the previously low spatial resolution available from Earth-based telescopes," Davies and her colleagues wrote in a new study published Tuesday (June 4) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. "SHARK-VIS ushers in a new age in planetary imaging."

SHARK-VIS, which was built by the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics at the Rome Astronomical Observatory, achieves its unprecedented sharpness by working in tandem with LBT's adaptive optics system, which shifts its twin mirrors in real time to compensate for blurring caused by atmospheric turbulence. Algorithms then select and combine the best images, which resulted in sharpest-ever portraits of Io achievable using an Earth-based telescope.

"Io was chosen as a test case because it was known to exhibit dramatic surface changes that would be detectable at the spatial resolution of SHARK," Davies told Astronomy. "As it happens, the first time we observed Io we found a large change had indeed taken place."