All but one of the stories in A Sunny Place for Shady People – the third short-story collection from Argentinian author Mariana Enríquez to be translated into English by Megan McDowell – concern hauntings, and ghosts. In My Sad Dead, a relatively affluent suburb bordered by crime-ridden slums is tormented by the apparition of a teenage boy shot dead in a robbery. In The Suffering Woman, a makeup artist experiences visions of a stranger’s slow decline into terminal illness. In Black Eyes, three volunteers for an NGO assisting the homeless of Buenos Aires have a blood-curdling encounter with two ethereal little boys wearing lederhosen.

The haunting is Enríquez’s perennial theme, and a word that, as she noted in an interview around the publication of her novel Our Share of Night, has no exact conceptual equivalent in the Spanish in which she writes. “The nearest would be ‘embrujado’,” she told the Southwest Review, “but that is bewitched. ‘Maldito’, but that implies a curse … We also use ‘encantado’, but that’s enchanted. ‘Fantasmagórico’, another word in Spanish that is near to ‘haunted’, is not exactly it either.”

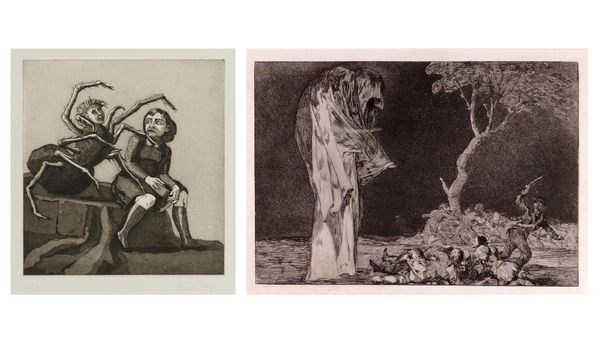

Enríquez is positing her work as an act of translation in itself: a transposition of the conventions of European gothic horror to the Latin American world. As she puts it, “translation of a tradition and its lexicon that doesn’t necessarily mirror Spanish words or even descriptions”.

Thinking of Enríquez’s work in this way deepens my appreciation of her consistent focus on the dynamics of the supernatural encounter, in which she draws on influences as diverse as Arthur Machen and Anne Rice. It also highlights this collection’s primary defect: an allegorical repetitiveness that drains some of these stories of their power to surprise or truly unsettle the reader. All of them are certainly competent exercises in horror, but the most thrilling for me were those that took a breakneck spin into other generic territories.

Take the title story, for instance. In A Sunny Place for Shady People, a journalist from Buenos Aires travels to Los Angeles to write an article on the cult that has spread around Elisa Lam, a young Canadian woman who drowned under mysterious circumstances in a water tank on the roof of a hotel.

As the journalist pounds Skid Row and visits the homes of old friends, she is haunted by another recursive spirit: that of her dead lover, Dizz, who struggled with an addiction that eventually claimed his life. The story is a neon-lit noir that feels like something fresh from Enríquez. Rather than simply presenting a new variation on the haunting-hauntee dynamic, A Sunny Place asks deeper questions about our relationships with the dead, both individually and communally. What if we want to be haunted? Do we search out horror to expiate guilt, or confront our trauma? The interpolation of Elisa Lam’s case – a real-world tragedy whose macabre details have for a decade been grist for the true-crime mill – makes these questions feel especially germane.

Enríquez is also very good at comedy. In Metamorphosis – a story that includes the most alluring description of a bloated cyst I have ever read – a middle-aged woman indulges in extreme body modification. Julie, in which a troubled young woman is sent to Argentina to undergo psychiatric treatment, is a sort of ghostly satire on middle-class politesse and diasporic identity. Many of Enríquez’s narrators share a sort of matter-of-factness that yields some hilariously cold one-liners: “Positive thinking is perverse, same as goodwill,” or “I don’t like old people … I roll my eyes when some employee at the shop takes days off because their dear old granny died. Who, I wonder, can suffer from that death so much they can’t go to work?”

At her best, Enríquez has an unrivalled instinct for the subtly appalling image, a Lynchian (David, not Paul) sense of how horror inheres within the benign – the stain on a hammock in a holiday rental, the roadside icon whose sickly pallor evokes death, a mouthful of wine spat over a kitchen table, “like watered-down blood on the white Formica”. Another highlight of the collection is Face of Disgrace, in which the generational trauma caused by an act of sexual violence is literalised as the recurrent visitation of an infective, faceless entity (a genuinely horrifying imaginative flourish typical of Enríquez: despite having no mouth, this entity whistles as it pursues its prey).

Overall, however, A Sunny Place for Shady People feels uneven in its development. There are some stories here that are conceptually strong, but feel sketchy or banal in their realisation, as though they had originally been written to a restrictive word count or deadline and never expanded to the full length they needed. There are instances when Enríquez’s prose suffers from the kind of dilatory imprecision that some reviewers found so offputting in Our Share of Night. At one point, a row of old refrigerators in the yard of an abandoned factory are described as “useless white and beige appliances of all sizes, arranged in lines like a labyrinth of dead soldiers”, while the factory itself looms overhead “like a trap of poisoned sweets, crowning the devastation”. A row of abandoned refrigerators could certainly be made menacing, but this glut of simile blurs the picture beyond recognition.

There were also instances of what felt like overly literal translation on McDowell’s part. In A Local Artist, a young holidaying couple have “all the ingredients needed for an intense breakfast”, instead of “opulent”, or merely “large”. Or in Nightbirds: “Mom cut the sole of her foot when she walked barefoot” – not incorrect, just syntactically awkward and redundant. Individually, these and other instances of maladroit writing didn’t disturb my pleasure in this collection too seriously, but cumulatively they contributed to the slapdash quality that some of the stories possessed.

As a fan of Enríquez since 2018’s Things We Lost in the Fire, I was disappointed that this collection oscillated so often between too much and too little. But it did nothing to shake my conviction that Enríquez, when she does just enough, is pretty much unbeatable.

• A Sunny Place for Shady People by Mariana Enríquez is translated by Megan McDowell and published by Granta (£14.99). To support the Guardian and the Observer buy a copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.