In the past month, my email has served up two contrasting examples of the state of scholarly publishing in African countries. The one was an invitation to celebrate the centenary of South Africa’s Wits University Press. The other, an academic report on the demise of Nigerian university presses. Between these two extremes, there are only a few functioning African university presses in 2022 – a recent survey found only 15 active presses out of 52 that claim to still be working.

The situation is similar in other universities in the global South, such as in India and Latin America, where most university presses function as printers rather than publishers. All the more reason, then, to celebrate the longevity – and significance – of a publisher like Wits University Press.

Active scholarly publishers are important because they provide a platform for research originating in a specific region. Scholars from the global South often go unheard and unseen, even in scholarship that focuses on their own countries and areas of expertise. As Mary Jay of the African Book Collective notes:

You can take a degree in African Studies without reading a single book published in Africa.

Local university presses are the main channel for such scholars to participate in broader debates and conversations, through books and journals.

If this sounds like a political justification for university presses, it is. Politics has always influenced scholarly publishing: who sets up a press, who provides the funding, and who gets published. The history of a publisher like Wits University Press is influenced by politics as much as by intellectual traditions.

The early history

Colonial South Africa became a Union with a white minority government in 1910. Wits University Press was established in 1922, the same year as its parent institution, the University of the Witwatersrand. The decision reflects how the university wanted to be perceived – as a new centre of learning and research that could, with time, stand on a par with colonial models. (Melbourne University may have been thinking the same, establishing the oldest university press in Australia in the same year.) The first title, economics professor Robert Lehfeldt’s The National Resources of South Africa, exemplifies the mission: that research by eminent local academics on South Africa could be conducted, and published, in that country.

The books that followed seem to bear out this early belief that a South African university press could make a mark if it focused on local expertise. Titles ranged from South African drawings, to drumming, to the citrus industry. The publishing list was inevitably affected by a shifting political context, and also often shaped by idiosyncratic individual interests or university priorities.

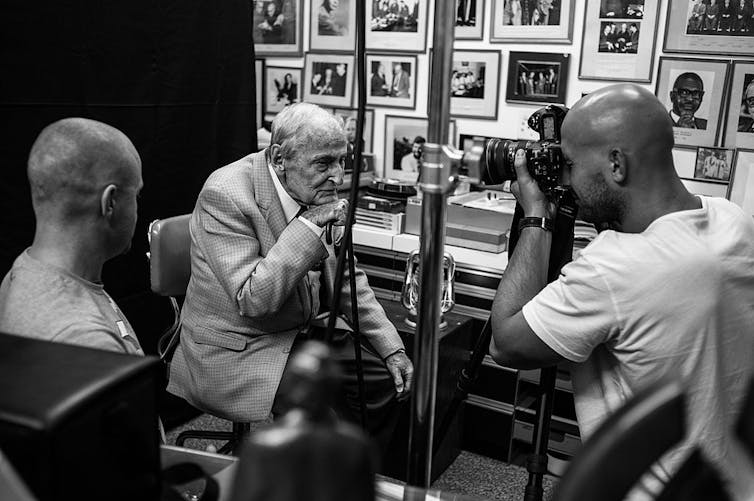

The key focus of publications for the first decades was the so-called “native question” and race relations. For instance, a founder member of the Wits University Press publications committee, JD Rheinallt Jones, was an advocate for social reform who set up the South African Institute of Race Relations. Leading social scientists published some of their most important research through the press, including Desmond Cole and Phillip Tobias.

Apartheid and censorship

Apartheid policies began to be entrenched by the white minority government from 1948 with harsh race laws segregating South African society, and controlling the circulation of information. The usual author profile at Wits University Press was, needless to say, white and male.

Exceptional black authors include the Reverend John Henderson Soga in 1930, and the range of writers published through the flagship Bantu Treasury Series launched by the press. This and the journal Bantu Studies (now African Studies), was the brainchild of Clement Doke of the university’s Department of Bantu Studies. His collaboration and friendship with Benedict Wallet Vilakazi, the first black academic at Wits, provided a fertile base for a publishing list in linguistics, dictionaries, ethnography and literature. In more difficult times, the Bantu Treasury Series would keep the press afloat. Titles began to be prescribed for Bantu Education schools and teacher training colleges from the 1950s, and the large orders were the main source of income for at least two decades.

As censorship was more heavily enforced from the 1960s, the more radical and well-known South African authors tended to publish abroad. There was a widespread perception that university presses would not take a chance on controversial texts, and could not assure an author of widespread distribution and readership.

It is true that Wits University Press was not a political publisher – some of its most enduring titles include Trees and Shrubs of the Witwatersrand (1964) and South African Frogs: A Complete Guide (1979). But, from the 1970s, state repression could no longer be ignored and the Wits University Press publishing list increasingly featured studies of trade unions, labour and law which served as proxies for overtly political books. Within a decade, the press could describe itself accurately as a “progressive publisher for a new South Africa”.

What still needs to be done

Wits University Press now attracts leading local academics with an emphasis on the social sciences and humanities rather than the natural sciences of the earliest days. The huge expansion in both the numbers and profile of academics in South Africa is reflected in stricter peer review and selection policies, rather than an unsustainable rise in titles. And the current concern of most university presses – technological developments that have changed publishing processes and formats – has been embraced. However, inequalities remain.

Will Wits University Press make it for another 100 years? The greatest ongoing threat has been there from the very beginning: visibility and relevance. Or rather, how a South African university press can make itself visible and demonstrate its relevance to often indifferent and highly competitive international markets. The press has actively explored co-publishing and distribution agreements in North America and Europe.

The west continues to dominate published scholarship about Africa. The solution is more visible research from Africa. Wits University Press has long been part of this solution.

Beth le Roux is a member of the Advisory Board for Wits Press. She writes here in her capacity as a scholar of university press history.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.