Detroit celebrated the reopening of its iconic railway station Michigan Central in June 2024 with a grand outdoor gala featuring an extravaganza of Detroit musical royalty – Diana Ross, Big Sean, Patti Smith, Jack White and Eminem – in the adjoining Roosevelt Park.

For years, the decaying structure had been a sore reminder of Detroit’s economic rise and fall. Now, after three decades of dormancy, an extensive restoration, spearheaded by the Ford Motor Company, has breathed life into the building again.

We are urban planners at Wayne State University in Detroit interested in the socioeconomic impact of urban policy.

Like most Detroiters, we are curious about the station’s history and buoyed by the new investment in it, and as urban planners, we are watching to see how its development will impact residents of the Motor City.

A monument to Detroit’s early industrial might

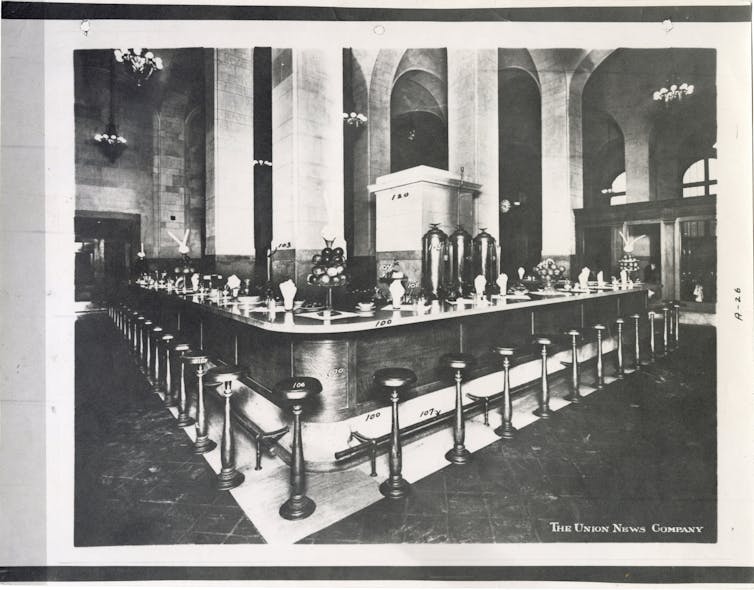

When it first opened, the station’s grand interior spaces were accessible to all.

Millions of immigrants seeking a better life arrived in Detroit by entering Michigan Central – which was sometimes referred to as Detroit’s Ellis Island.

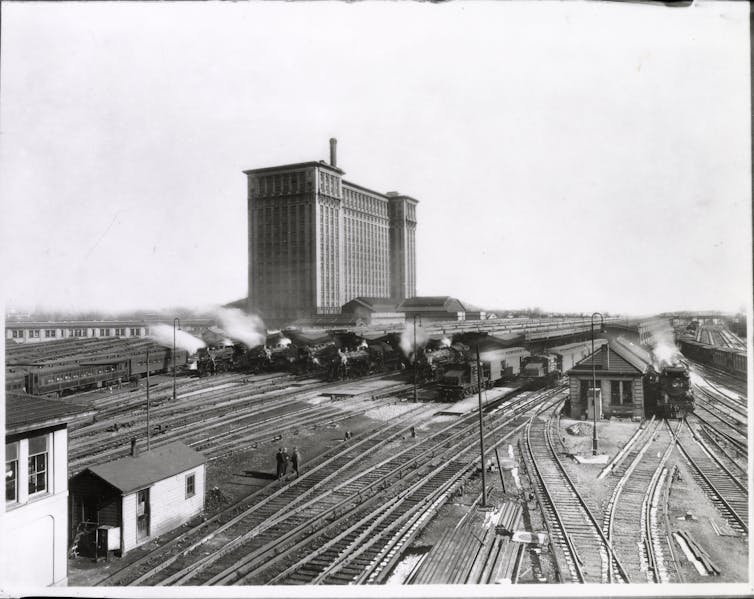

The Beaux-Arts gem completed in 1913 served as a monument to Detroit’s early industrial growth. The same year it opened, Henry Ford implemented the automated assembly line at the Highland Park plant.

Designed by Warren & Wetmore and Reed & Stem, the architects behind New York’s Grand Central Terminal, the building exemplified the early 20th Century City Beautiful movement. With a roof height of 230 feet (70 meters), it was the tallest train station in the world at the time.

The station consisted of a waiting room canopied by tiled vaulted ceilings adorned with medallions and bronze chandeliers. It housed a light-filled concourse and a columned ticket lobby towered by an 18-story office complex. The 500 offices were reserved entirely for the railroad industry and accommodated train personnel, passenger auditors and other workers.

The station’s original purpose was to connect the newly constructed Michigan Central Railway Tunnel with Windsor, Ontario – a 1 3/8-mile tunnel under the Detroit River that replaced ferry transit for railroad cargo. Due to the distance to downtown, passengers transferred via electric streetcar to and from the station.

During peak operation in the early 1940s, Michigan Central Station served more than 4,000 travelers daily.

Post-war decline

By the 1950s, inner-city streetcar transit ridership began to decline due to the introduction of public transit buses and increasingly affordable private automobiles. Detroit’s streetcar system went offline in 1956, isolating the station from the central business district.

At the same time, Detroit’s population began to diminish, with the destruction of entire neighborhoods and the development of five expressways that displaced tens of thousands, mostly African-American, residents.

By 1974, the Ford Motor Company closed its last plant in the city.

In 1988, Michigan Central Station terminated service.

Decades of dereliction and ‘urban explorers’

By this time, Detroit hosted a landscape of abandoned skyscrapers, attracting urban explorers and photographers alike.

Although the station’s splendor had faded – or precisely for that reason – it was featured in Michael Bay’s post-apocalyptic film “Transformers” and revered by musician Carl Craig in the documentary film “Techno City”.

Testimonials from urban explorers describe the ease of entering the abandoned station in the 1990s – considered a sort of rite of passage for young Detroiters that one art student compared to a visit to the museum.

After the station had survived three decades of failed restoration proposals, Detroit City Council ordered then-owner billionaire Matty Moroun in 2009 to demolish the heavily deteriorated building. A lawsuit contested the resolution, citing the station’s landmark status under the National Historical Preservation Act of 1975, and saved it from the wrecking ball.

New life

In 2018, the Ford Motor Company acquired the station with the goal of creating a hub for its foray into electric vehicle manufacture and new destination for tech and venture capital startups.

The building had suffered severe damage, caused by years of neglect and vandalism. The basement was flooded, most of the tiles had fallen from the ceilings, and the steel roof had nearly collapsed.

Ford hired the architecture firm Quinn Evans, which sorted through historical photos and archives of architectural plans to assist in restoring the building.

Twenty-nine thousand Gustavino tiles were reinstalled – nearly all original. Designers 3D-printed replicas of former medallions and cast massive replacement chandeliers.

Before and after views of the tiles ceiling at Michigan Central. Source: Michigan Central

A stonemason spent 428 hours hand-carving a capital column from a 21,000-pound limestone block, supplied by an obsolete quarry in Indiana, which had been resurrected solely for the purpose of the station’s restoration.

In all, more than 3,000 tradespeople dedicated 1.7 million hours to the project.

In the spirit of a city whose Latin mottos translate to English as “We hope for better things” and “It will rise from the ashes,” many once-looted items, such as parts of the iconic ticket lobby clock, were anonymously returned.

Informal history was preserved as well, including a section of graffiti and blemishes carved into the original marble floors by the thousands of shoes that had traversed the station.

Ford’s vision for a ‘global mobility innovation hub’

Ford invested US$950 million into the restoration of the railway station, as well as the design and construction of the surrounding 30-acre Michigan Central campus, which includes recreational spaces and a variety of other buildings with offices, retail, a restaurant and parking facilities.

The adjacent former Detroit Public School Book Depository houses one of Ford’s main partners, Newlab, a tech incubator founded in New York City.

In an interview with WXYZ-TV Detroit, executive chair Bill Ford Jr. said that he is committed to an open platform and welcomes collaboration with other car companies.

When asked why he chose Detroit for Ford’s next chapter, instead of another city with an already existing tech infrastructure, he said that Detroit is: “an incredible place to work, where your family will also love to be, and it’s affordable.”

Detroiters’ concerns about the future

The City of Detroit and the State of Michigan pledged an estimated $240 million in property tax abatement and favorable policies – such as the new Transportation Innovation Zone, which fast-tracks novel mobility and robotic testing around Michigan Central – to backstop Ford’s investment.

In 2016, Detroit approved an ordinance requiring developers who receive tax incentives larger than $1 million for projects valued higher than $75 million to negotiate with the surrounding community potential benefits to offset the project’s negative impacts in the neighborhood – for example, invest in affordable housing. According to the latest compliance report, Michigan Central has satisfied most agreements.

But for some Detroiters, the development is a double-edged sword. With significant investment from Ford and its top tech partners, Detroit and its Corktown neighborhood expect a rise in population, tourism and spin-off business dollars that some fear could lead to a rise in housing costs and displacement.

Indeed, Ford’s investment began shifting neighborhood housing dynamics long before Michigan Central’s grand opening, with a surge in housing costs hitting renters hardest. With project boosters comparing the new Michigan Central to California’s Silicon Valley, a place that has some of the most expensive housing markets in the nation, many residents worry that they eventually will be priced out of the neighborhood. In anticipation of a big boom, rents for retail space have increased substantially; however, many storefronts have remained empty.

How Michigan Central will affect housing, job market and business in its adjacent neighborhoods is yet to be revealed. For now, visitors and tenants alike can revel in the wonders of walking on the historic grounds of Roosevelt Park into the restored grandeur of the Michigan Central Station.

Nothing to disclose.

Mila Puccini does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.