Less than seven percent of the adult population in the United States has optimal cardiometabolic health, according to a study published Monday in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. That’s a “devastating health crisis” facing the nation, according to the researchers. The work was led by a team from Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

Meghan O’Hearn, a doctoral candidate at the Freidman School and the study’s lead author tells Inverse, “We looked at trends over this 20-year period of time to see if health interventions and policies — be they public health or clinical — are actually making a difference.”

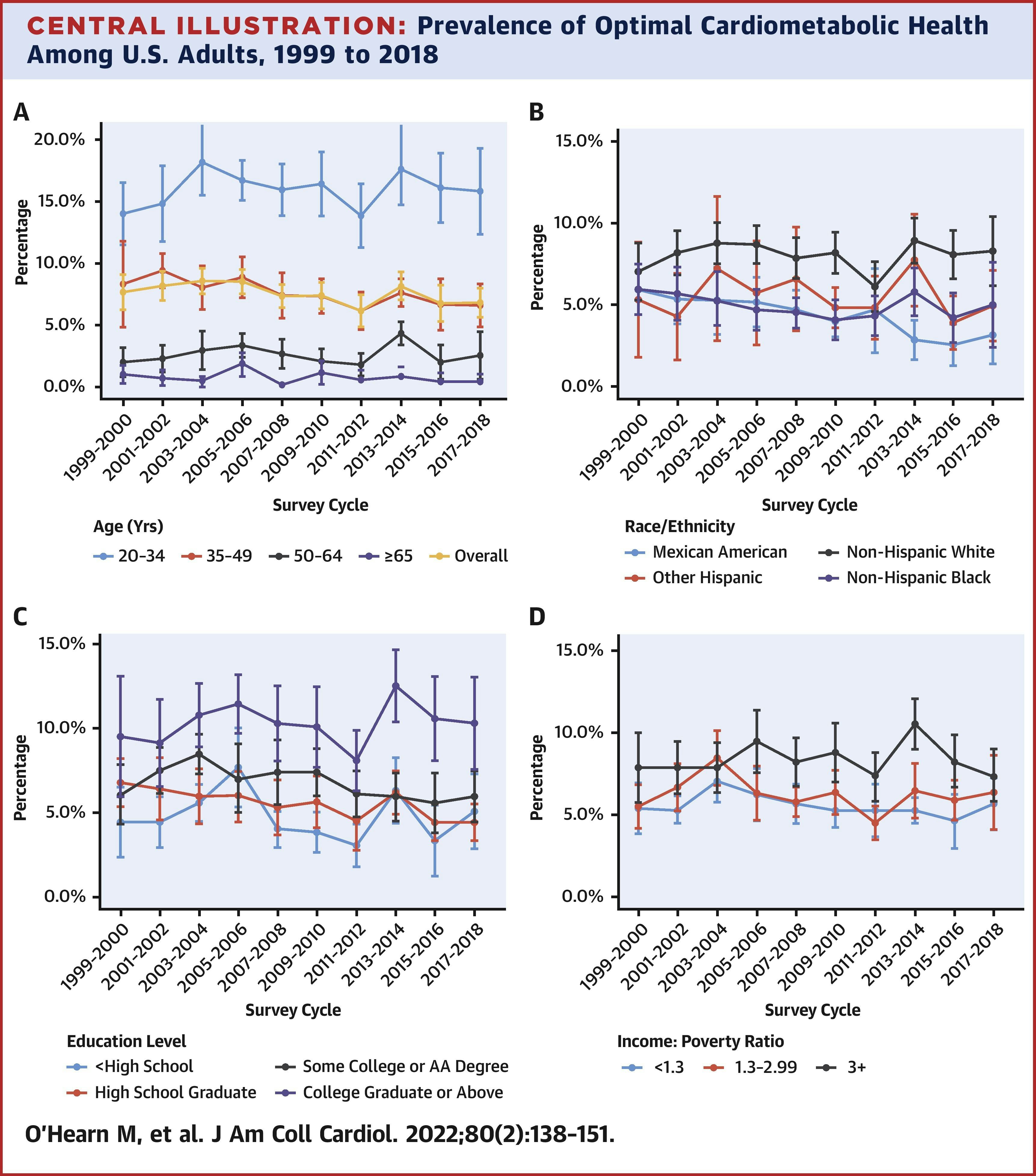

What they did — Using data from the 10 most recent cycles using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, researchers assessed the cardiometabolic health of about 55,000 people over the age of 20 from 1999 to 2018. They looked at five components of cardiometabolic health: blood pressure, blood sugar, blood cholesterol, adiposity (overweight and obesity), and presence or absence of cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke, etc.).

The researchers also analyzed health among different demographics: age, sex, education, race, ethnicity, and income. These metrics were vital, O’Hearn says, because it helps them understand if health disparities “are getting worse, or if they're getting better. Is the gap between different population segments widening? Or is it getting more narrow?”

Those trends really matter from an intervention and policymaking perspective, she says. If there was a positive trend over 20 years, in which health disparities among certain groups were narrowing and overall health was improving, it might indicate that the interventions policymakers implemented 20 years ago were working well.

Unfortunately, that’s not what O’Hearn and her colleagues found.

What they found— As of 2018, only 6.9 percent of Americans had optimal levels of all five metrics. Trends for adiposity and blood glucose worsened significantly between 1999 and 2018. In 1993, one in three people had “optimal levels of adiposity”; by 2018, that number was 1 in 4. Similarly, in 1999 two out of five people were either diabetic or had prediabetes. In 2018, the number of people with either of those disorders increased to more than six in 10.

Social determinants of health like “food security, structural racism, social and community context, may put individuals in different demographics at increased risk of health issues,” she says.

It’s noteworthy that the data used was taken pre-pandemic, and O’Hearn says she wouldn’t be surprised if our collective cardiometabolic health has gotten even worse.

“The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have affected people’s access to healthy, affordable foods,” she says. “Many people have been less physically active during the pandemic as well. So if I had to speculate, I would say things like glucose levels are probably getting worse.”

What it means for the future— O’Hearn notes that she and her colleagues are concerned with more than just avoiding poor health; they want to understand how many people are experiencing optimal health.

“We’re thinking about it in terms of ‘is the United States healthy? Are you experiencing good health and well-being? And very likely, we’re not.”

It doesn’t have to stay that way, though, O’Hearn says. Agricultural subsidies and expanding nutrition assistance programs like SNAP and WIC could help more people access affordable, nutritious food.

“The standards for those programs were all developed like 50 years ago when the problems of the day were very different. Those could be enhanced,” she says. Similarly, “So if we could make EBT card [which SNAP recipients use to pay for food] go further in buying healthy food, we could help alleviate some of these issues,” she says.

Another idea, O’Hearn says, is promoting initiatives where doctors can prescribe healthy foods and insurance companies will cover it, whether that's Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance. Because we’ve shown it can actually be more cost-effective to use healthy foods to prevent some of these issues that won’t require pharmaceuticals or other interventions down the line. Because a lot of diabetes and other conditions really are driven by diet quality.”

There’s also a lot that can be done to enhance “consumer and patient education,” she says. Ideally, this would happen on both the clinical level — between a patient and doctor — as well as a public health level, with the implementation of broader programs. That may include working with the private sector and assessing “how investors can actually drive a healthier food system by investing in companies that are making objectively healthier, more affordable, and more widely available goods.”

“We talk a lot about what the government should be doing, and that’s good,” she says. “But I think the private sector is very powerful and I think there’s a lot of opportunity there.”