The poetry of Gwen Harwood was strikingly unconventional, yet for most of her career, she was not considered especially radical. This was partly because she tended to use traditional forms; in a time of experimentation, new forms – or no form at all – seemed synonymous with new ideas.

This was a misconception, of course. Harwood – a virtuoso of poetic form – could be outrageous in any metre. But she was quite content to pass for the “kindly, respectable” housewife-poet her readers seemed to want her to be. As she wrote in Littoral, she daily put on

… the same

mask: my familiar, anti-grand

manner.

Such was the power of this mask – and such the general discomfort, for much of the 20th century, with women who did not fit the conventional mould – that even Harwood’s more obvious challenges to the status quo were quickly transformed into something benign. Her literary hoaxes were neutralised as “mischief”; her clever use of pseudonyms was greeted with bemusement.

The handful of poems she wrote in the late 1950s and early 1960s challenging the tenets of Holy Motherhood (themselves published under pseudonyms) were more difficult to dismiss, though Harwood herself, ever wary of attack, would later actively distance herself from them.

With the rise of the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s, these poems were seized upon by those who, like Nancy Cato, felt they expressed

what every woman stifled by suburbia & being a housewife and mother has felt; particularly that savage hatred of one’s “nearest & dearest” for getting in the way of creative work.

Always the subject, never the object

Today, the boldness and originality of Harwood’s so-called “suburban” poems are widely recognised. Yet her ground-breaking poems of female sexuality from the 1970s remain little known.

Harwood’s love poems are still startling, disconcerting, even shocking. As Stephanie Trigg pointed out in 1994, works such as Carnal Knowledge I & II and Meditation on Wyatt I & II, along with many others, celebrate “the sheer physicality of sexual love”. Even more boldly, they speak from the viewpoint of a woman, who is “always the subject of love, never the object” – thereby reversing centuries of poetic tradition.

Critics were uneasy with these poems from the first, all too aware of “the fearsome social implications if such passionate poems could be proven autobiographical”.

Harwood was then in her fifties, a veteran of a long marriage, known to be a devoted wife and mother, who had lived a seemingly quiet life in suburban Hobart. Even in the era of sexual revolution, readers were reluctant to associate a respectable woman of her years with sexual passion. Much safer to approach these dazzling erotic poems as refractions of her dim distant girlhood or, better yet, allegorical explorations of abstract philosophical themes.

The problem only intensified as Harwood grew older and more distinguished. A much-loved figure on the Australian literary circuit in the 1990s, she was treated, as she once wryly confessed, “like the queen mother”. This surfeit of respect made it difficult for anyone to engage seriously with – or even notice – her erotic poetry. As Trigg put it,

We are so charmed by Harwood’s public persona that we are reluctant to attribute such ardent poetry to the grandmotherly figure before us.

Harwood was mostly happy with this. She had no intention of risking a scandal, even if the cost of her privacy was a diminishment of her artistic achievement.

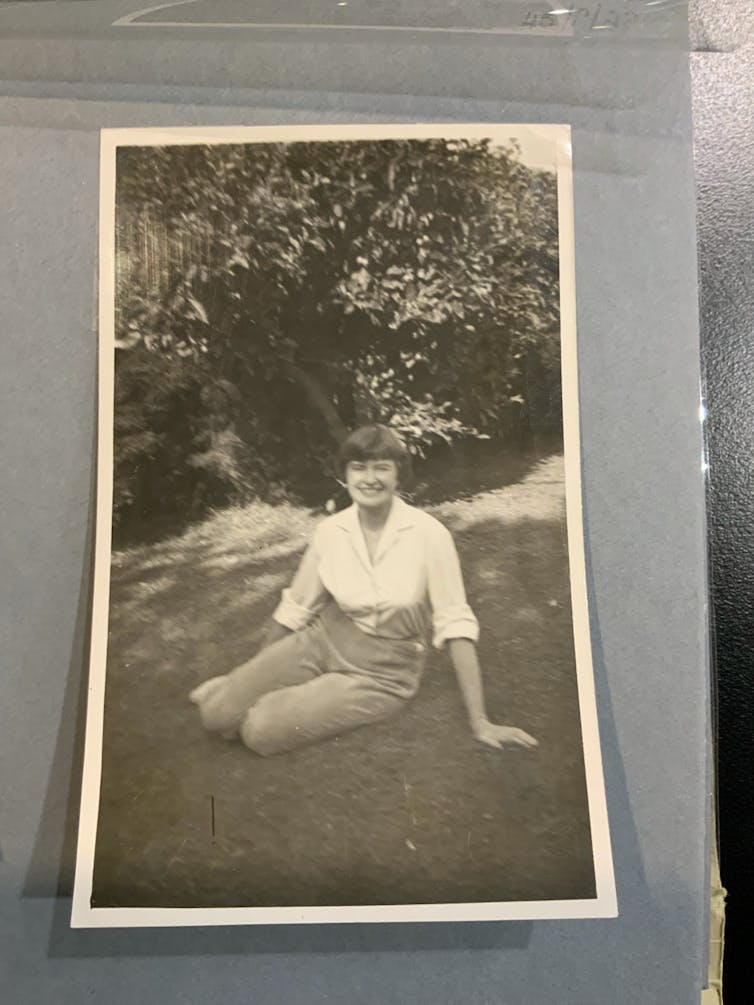

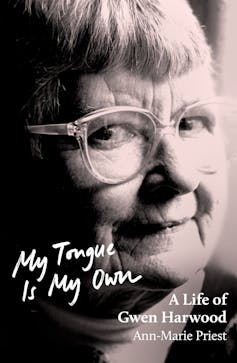

Yet the ardour of these poems was certainly Harwood’s own. One of the first things I discovered in researching Harwood’s biography, My Tongue Is My Own, was that as a 17-year-old fresh from school, she had begun an affair with her 50-year-old married music teacher, the illustrious Dr Robert Dalley-Scarlett – a relationship she would later insist was entirely joyful.

Quite soon after this, she fell in love with a young curate, Peter Bennie, who occupied all her “thought, affection, hope and longing” for five years. Nevertheless, she did not end her “pleasant” affair with Dalley-Scarlett for another couple of years.

Nor did Harwood hold herself aloof from other men in her social and professional circles (she was a musician), some of whom would later appear in her poems. Her dearest friend at this time was her former art teacher, Vera Cottew, with whom she was also very much in love – though this was not the way she would then have described the relationship. It soon became clear to me that there was nothing conventional about Harwood’s attitudes to love and sex. She was a sexual radical at 17, and would be one at 70.

Most unexpected of all, perhaps, given her upbringing in a white, middle-class Brisbane household in the 1920s and 1930s, was Harwood’s lack of any sense that sex was sinful. In the midst of her affair with Dalley-Scarlett, and as a consequence of her passion for Bennie, she joined the Anglican Church. A couple of years later, thinking she might have a vocation to religious life, she entered a tiny Anglican convent in Toowong.

Yet somehow she remained entirely unburdened by Christian concepts of female sexual purity. Much as she loved the church, revelling in its sensual delights – the vestments and candlelight, the ravishing music, the passionate poetry of the Psalms and the Song of Songs – she seems to have simply dismissed its moral teachings on sex. She put no spiritual value on virginity, and saw no evil in practices the Church condemned as fornication and adultery. To her, sex was always good – even holy.

In this she was influenced by Christian mystics such as John of the Cross and, closer to her own time, Therese of Lisieux, whose writings flame with sexual passion. She was also devoted to the work of 17th-century poet-priest John Donne, who would become one of her most abiding influences. His assertion, in Love’s Progress, that sex was the “right, true end of love” was central to her own understanding of sexuality.

Harwood would even appropriate his line for her own love poetry. In the early poem Tom the Rhymer, for instance, a pair of adulterous lovers would find

… love’s right

true end in bodies.

In a much later poem, A Valediction (the title references Donne’s A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning), a woman finds solace after her lover’s departure in the knowledge that he would one day

come again to me, my body

to its true end will give him joy.

Harwood’s sense that sex was the happiest expression of human attraction sat alongside her conviction that it was perfectly possible – and morally unimpeachable – to love more than one person at a time. Even before she married, at the age of 25, she was aware that her “attitude” was “not as monogamous” as her betrothed might have liked. She believed in marriage, but not in sexual fidelity. To her, it was self-evident that love given to one person was not taken from another. She used the analogy of sunshine: the sun is not less warm if it shines on two people rather than one.

As a girl, Harwood was “always in love” with someone or other; as an adult, she was – as she freely confessed – “attracted to a great many people”. She saw it as part of her nature to be passionately drawn to others, both male and female, and if that attraction manifested itself sexually, that was cause for joy.

In the early years of her marriage, she made a concerted effort to fit in with her husband’s expectations – to bend herself, as she would later put it, into his “frames”. As she grew older, however, she began to resent the damage she had inflicted on herself in trying to meet his requirements. Once her children were launched, she considered herself free to go her own way. Her well-known poem An Impromptu for Ann Jennings can be read as her manifesto.

Without grandstanding or fuss, and without leaving her marriage, she claimed her right to move – and love – where she would.

Honesty and wildness

This is the biographical context for the radically sexual poems of the 1970s – as well as for a number of more cautious, and often more obscure, poems of love and sex from earlier decades.

Some of the earlier poems were written in a male voice, either as a form of camouflage or because of Harwood’s uncomfortable awareness that her attitudes did not conform to feminine stereotypes. As she said of The Wine is Drunk (which riffs on American poet Richard Wilbur’s A Voice from Under the Table), she sometimes adopted a male point of view because what she wanted to say sounded “odd in the feminine voice”.

By the 1970s, however, her poetic voice was confidently female, even when it told of experiences that might have been considered unseemly for a woman. Her poems were more direct and less ornate than in the past. As Diane Dodwell wrote in 1977, reviewing Harwood’s third book, there was a new directness in Harwood’s poetry, an “uncompromising emotional honesty”. Dodwell also noted a startling “quality of wildness”.

But as Harwood herself declared in An Impromptu for Ann Jennings, she had always been “wild”, even when (like Ann Boleyn in Thomas Wyatt’s Whoso List to Hunt, which Harwood is here riffing on) she seemed “tame”.

The wildness of Harwood’s love poems springs, in part, from their sheer eroticism: they are songs of joy and triumph in which a mature woman claims her sexual power. Carnal Knowledge I begins in medias res with the poet, exhausted, crying out to her lover (that “fabulous animal”) to “be human” and let her rest. Get some sleep, she urges him – before promising to reawaken him, both literally and sexually, by biting and caressing him.

As Trigg points out, the poet depicts herself as both the initiator of sex and the creator of the world – which she builds “from what’s to hand”, the “flesh my fingers cup”. As Trigg declares: “It is a most confident rewriting of traditional scenarios, and evinces a commanding sexual politics”.

Far from transcending the material plane, Harwood’s lovers infuse the material world with the spiritual. They step beyond the boundaries of the human to become part of all that is, sprouting “wings for blue distance” and

fins to sweep

the obscure caverns of your heart.

They learn “leaf-speech” and hold apart “sea-strip and sky-strip” to create the hills and roses that bless their tryst. In sex, they know one another – and the world – in a new way, with a knowledge that is alien to reason, and even to words. “Bone to my bone I grasp the world,” the poet declares. “But what you are I do not know.”

Such knowledge is not always joyful. In Night Flight, the poet is on a plane, flying away from her beloved. Musing on their time together, she realises that she has learned more by dancing with him than by talking to him. Her knowledge came not through words but through “heat-lightening”, through the “rapture” of love. But it is a dark knowledge:

sorrow has taken hold

of this one whom I love.

It is a knowledge she feels “through my skin”, explicitly carnal, known in, through and as the body:

I feel it, as we move, […]

Absorb it, eye to eye;

suffer it; drink it in;

clasp it, immediate;

fill with it, bear its weight.

She goes on to abandon herself to the “molten afterglow” of love, where

each sense

surrenders all, as in

some rapture of the deep.

This exaltation, however, is one she experiences alone, the “sustaining violence” of love sending her climbing

in stormy air to lie

alone in the black sky.

Some of Harwood’s love poems explore this violence, poems with disturbing undertows like Night Thoughts: Baby and Demon and The Owl and the Pussycat Baudelaire Rock, which draw on the language of seventies drug culture. Others are playful, full of puns and jokes and allusions to other poets.

Sometimes the language is explicitly sexual, sometimes metaphorical. In Plato’s Cave, for instance, a visit to an actual cave formation (King Solomon’s Cave in central northern Tasmania) becomes a vehicle for the depiction of simmering sexual passion:

There’s moisture everywhere like sweatshine glossing

bodies in nakedness. Columns on all sides

and nature’s genial clefts.

Whether literal or figurative, these poems are strikingly specific. They do not deal in abstractions: they situate this pair of lovers in this specific time and place. “My love and I stood still / in the roofless chapel”, begins The Sharpness of Death:

… My

body was full of him, my

tongue sang with his juices, I

grew ripe in his blond light.

It is a moment of utter plenitude. It is also a manifestation of one of Harwood’s abiding preoccupations as a poet: how to stay “in the light of now which transfigures sexual love”. In this moment of ecstatic sexual being, death itself is vanquished.

Beyond any underlying philosophy, however, these are poems in which a woman speaks directly (not without labour or art, but truthfully) about her sexual experiences – a rare phenomenon in the 1970s, and not common, perhaps, even now. She does not talk about “true love” or “soul mates” or deploy any other of the worn-out tropes of romance. Instead, she depicts a love that flows freely and has transformative power.

Harwood’s love poems are full of surprises, even for a generation that accepts that women can be sexually alive at any age. For too long, our reading of these poems has been constrained by our preconceptions about the women of her time, about Harwood’s own life, and about female sexuality more generally. It is time to throw off those constraints and approach these poems anew.

Ann-Marie Priest ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.