Rancher Michael Vickers, Kinney County Sheriff Brad Coe, and the governments of Kinney and Atascosa counties filed a lawsuit in federal court on July 31 claiming that the Biden administration’s policies and actions have resulted in “the current, massive flood of illegal entries by foreign nationals from around the world.” They are asking the court to declare several Biden-era immigration policies unlawful.

The suit, which is pending in the Southern District of Texas in Corpus Christi, details several allegedly unlawful policies or actions Biden has instituted since taking office, including a parole program for migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela that allows migrants with a sponsor in the United States to come work in the country for up to two years, and the family reunification parole process that has allowed some Latin American immigrants to bring relatives to the United States. The plaintiffs are also asking the court to declare unlawful the termination of the Migrant Protection Protocols, commonly referred to as the Remain in Mexico program, as well as the administration’s stoppage of border wall construction.

The plaintiffs are represented by the Immigration Reform Law Institute (IRLI), the legal arm of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), an ultraconservative nonprofit focused on immigration restrictions. “By creating the border crisis on purpose, the Biden administration has defeated the purpose of the immigration laws,” IRLI attorney Chris Hajec said in an email to the Texas Observer. “That’s not just wrong, but a violation of Biden’s constitutional duty to execute the nation’s laws faithfully, as we intend to prove in court.”

The lawsuit comes at a time when the number of illegal crossings has dropped. Border Patrol agents recorded 84,000 apprehensions in June, only a third of those reported in December 2023. Recent declines in illegal crossings are due in part to a crackdown in Mexico and Biden’s June executive order, which suspends asylum access when daily crossings reach a certain threshold.

The defendants include President Joe Biden, the Department of Homeland Security, and Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, along with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

The lead plaintiff is Michael Vickers, a veterinarian who also owns a 1,000-acre ranch in Brooks County. Brooks County, which does not border Mexico, has a population of 7,000 and a long history of recorded deaths of migrants, who die in remote areas while trying to bypass its Border Patrol checkpoint. For nearly two decades, Vickers has led a paramilitary-style, civilian patrol group called the Texas Border Volunteers. Vickers and his wife, Linda, were once affiliated with the Minutemen, an organization that former President George W. Bush called a “vigilante” group.

In the suit, Vickers alleges that undocumented immigrants have damaged his property as a result of Biden’s policies. He has incurred more than $50,000 in fence and gate damages since 2021 and the value of his property has decreased, according to the lawsuit.

At times, Vickers and other Texas Border Volunteers have offered emergency help or assisted with body recoveries. But the group sees its main mission as finding and detaining migrants, and has a history of allegations against it, including members tying migrants’ hands together with shoelaces or zip ties and taking their belongings, and members pulling weapons on migrants, as the Observer reported in 2014. The group was incorporated in Texas in 2006, state business filings show, and has been tax exempt since 2008, according to Internal Revenue Service records.

Charles Gilbert, a former member of Texas Border Volunteers, alleged in a 2014 interview with the Observer that the organization “operates as a militia in plain sight and no one is calling them on it. They’ve done a good job at suppressing what they do.” (Private paramilitary groups are illegal under the Texas Government Code.)

In an interview with the Observer on Friday, Vickers rejected Gilbert’s characterization: “We’re not a militia. What we are is a neighborhood watch group.” Texas Border Volunteers work “hand in hand” with Border Patrol—and the Texas Rangers assist the group with background checks of their members, he said.

“We work hand in hand with law enforcement. Everything we do is within the limits of the law, and what we are allowed to do under the regulations of the law, and nothing else,” he said. “And any kind of criticism is usually from somebody that is lawless.”

When asked about past allegations that members of the group had tied migrants’ hands with shoelaces, Vickers first blamed any bad behavior on leftist infiltrators, then later admitted it happened—but said the group used zip ties, not shoelaces. “I’m not going to discount that. We did have a sheriff’s deputy with us that was involved in that.” He claimed that all the migrants whose hands were tied were gang members from El Salvador. “They all had gang tattoos, and we have no regrets for doing what we did,” Vickers said.

Per Texas Border Volunteers protocol, they continue to detain people, he said. “Quite frankly, now this is part of our operating protocol,” Vickers said. “We are gonna sit on people, detain them, and have law enforcement pick them up.”

As for the zip ties, Vickers said they will probably not use them in most cases, but he wouldn’t rule out the idea. “If they are recognized as being criminals and gang members, that could be one of our options,” Vickers said.

Apart from Vickers and his wife, the Texas Border Volunteers’ other directors listed in its most recent state filings do not live near the border. Their mailing addresses are in the Dallas and Houston suburbs of Southlake, Midlothian, and Montgomery, and Adkins, an unincorporated community outside of San Antonio.

Texas Border Volunteers has worked with the Texas Department of Public Safety’s Brush Team, a specialized unit focused on intercepting smugglers and migrants in remote ranchlands near the border, according to Vickers and social media posts from other group members.

Last fall, Texas Border Volunteers held a FAIR event on Vickers’ ranch. They hosted sheriffs and legislators from 28 states, and held a briefing with a Falfurrias Border Patrol agent-in-charge, the Brooks County sheriff, Texas DPS ranch liaison, and others, a Texas Border Volunteers member wrote in an October 2023 Facebook post.

The Texas Department of Public Safety did not respond to a request for comment for this story or to written questions about its relationship with Texas Border Volunteers.

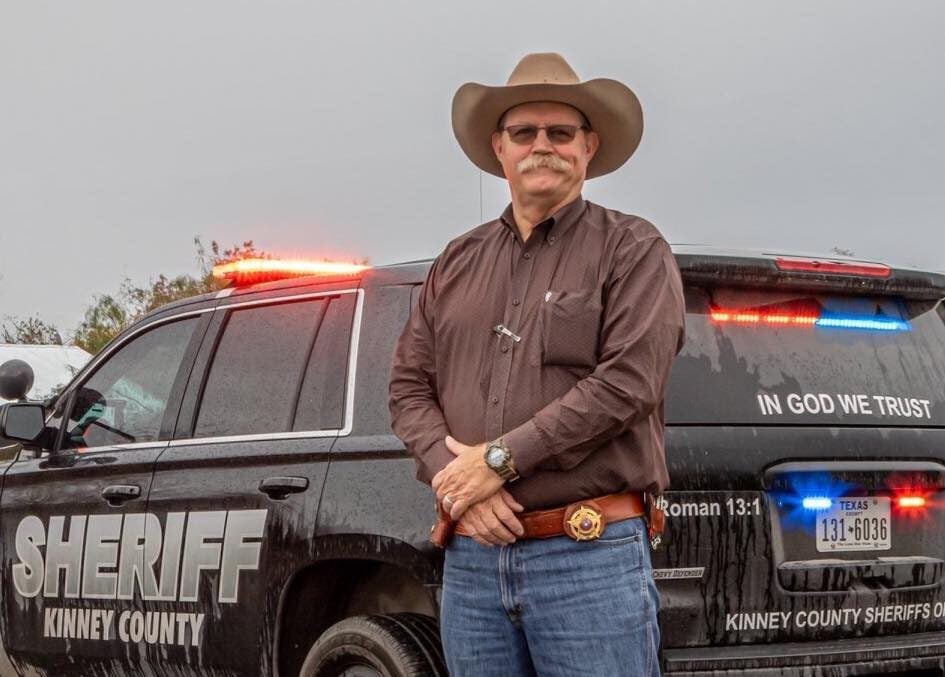

The second plaintiff in the lawsuit is Kinney County Sheriff Brad Coe, who is claiming in the lawsuit that the Biden administration’s policies have forced him and Kinney County to “detain more aliens who commit crimes in the county” at “significant costs”—which include “the financial cost of detention and the consumption of scarce county law enforcement resources.”

Coe has previously been the subject of legal action and criticism over his county’s treatment of migrants. Kinney County, which is also sprawling and sparsely populated, is home to a 17-mile stretch of the border.

In 2023, the ACLU of Texas sued Kinney County, Sheriff Coe, Val Verde County, and its Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez, a state contractor, and other officials on behalf of migrants who’d been arrested under Operation Lone Star and detained well after their trespassing charges had been dropped. The case is ongoing.

Coe has also been criticized by The Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, a nonpartisan legal group, over his relationship with border vigilante groups—which included an organization that conducted armed patrols in his county involving men with previous criminal convictions who could not lawfully carry guns, as revealed by a Observer and Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting report in May.

Last month, the Observer reported on Sheriff Coe’s plans to purchase pepper ball and tear gas launcher rifles to potentially use against migrants to deter them from crossing the border. Coe did not respond to the Observer’s requests for comment on the lawsuit.

Atascosa County, which joined Kinney County and the other plaintiffs, is a sparsely populated county near San Antonio. Jourdanton, the county seat, is more than 130 miles from the international border. The Atascosa County judge and attorney did not return requests for comment.