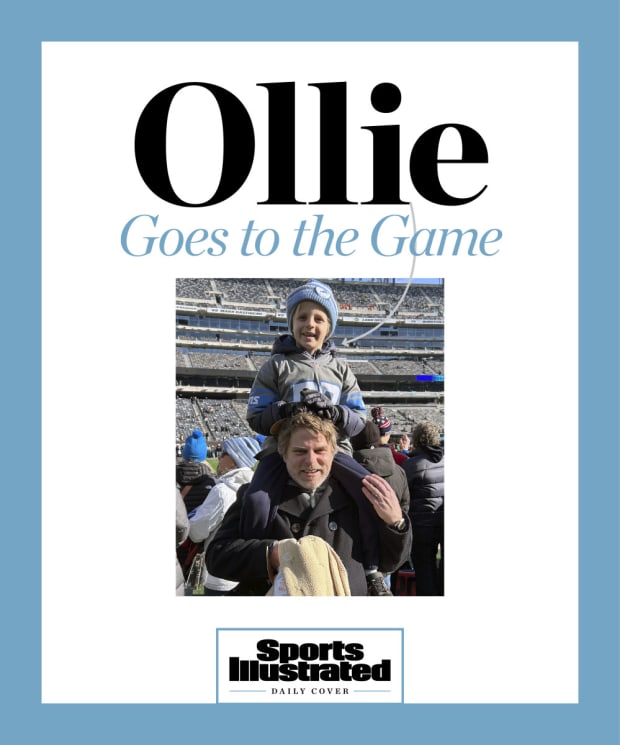

My 7-year-old son and I are in New Jersey, and we’re about to witness a miracle.

It is a crisp December day, the sky is Honolulu blue and the Detroit Lions are going to win the game. We cannot know this, of course—in fact my son and I, die-hard Lions fans (is there any other kind?), are pretty damn convinced they’re going to lose. Down four points with two minutes left, Detroit is facing fourth-and-inches just shy of midfield against a staunch Jets defense, so it’s not looking good. Ollie even says it to me, “They’re going to lose, Daddy. They’re going to do a dumb pass play and blow it.”

Courtesy of the Plimpton Family

What are we even doing here? Why have I brought my young, impressionable son to this gladiators’ coliseum, this palace of excess and violence? Behind us, a massive, drunken Jets fan is scowling at us and cursing. Actually, all around us, Jets fans are cursing (“That’s bulls---!” “F---ing cheaters!” “You suck, refs! What are you, from Detroit?”), and, at a certain point, my son asks, “Why is everyone using such bad language, Daddy?”

Yes, this is a strange place to bring a child—and if I’m being honest, football is a strange passion to pass on to someone you love. To assuage the fatherly guilt, I’m forever seeking out teaching moments, and right now, with the Lions about to go down, I’m thinking about spinning loss into a lesson. Though the truth is that, having been a Lions fan since before he could talk, Ollie’s well acquainted with loss and all its “lessons.”

And then the Lions go ahead and do the exact dumb pass play Ollie thought they would—but somehow, miraculously, it works. Tight end Brock Wright is wide open, catches the ball and thunders down the field for a 51-yard touchdown. Ollie and I cannot contain ourselves: We are jumping up and down and hugging each other and screaming with joy.

Who else behaves this way—game show contestants? Not too many circumstances in this peculiar life allow us to leap up and down and embrace one another, I guess. Yet every day in stadiums (and living rooms) all around the world, such outlandish merriments are commonplace. It’s the strangest thing, how happy it can make you when your team emerges victorious—and how utterly depressed you can be when it loses. As Ollie and I leave the stadium, there is a giant bounce to our step, we are helium-light, filled with sunshine, and we are hooting and hollering and high-fiving the occasional Lions fans we encounter, all of us behaving as if we ourselves had scored the touchdown. As if somewhere up there in the Honolulu-blue sky with its perfect little puffy white clouds, some benign presence is smiling down upon us. On our way to the car, Ollie comes up with the perfect name for the whole experience: “The Miracle at . . . wait a second, what’s the stadium called again, Daddy?” “MetLife.” “Right,” my son says: “The Miracle at MetLife.”

To be fair, it sometimes feels like any time the Lions win a game, it’s basically a freaking miracle.

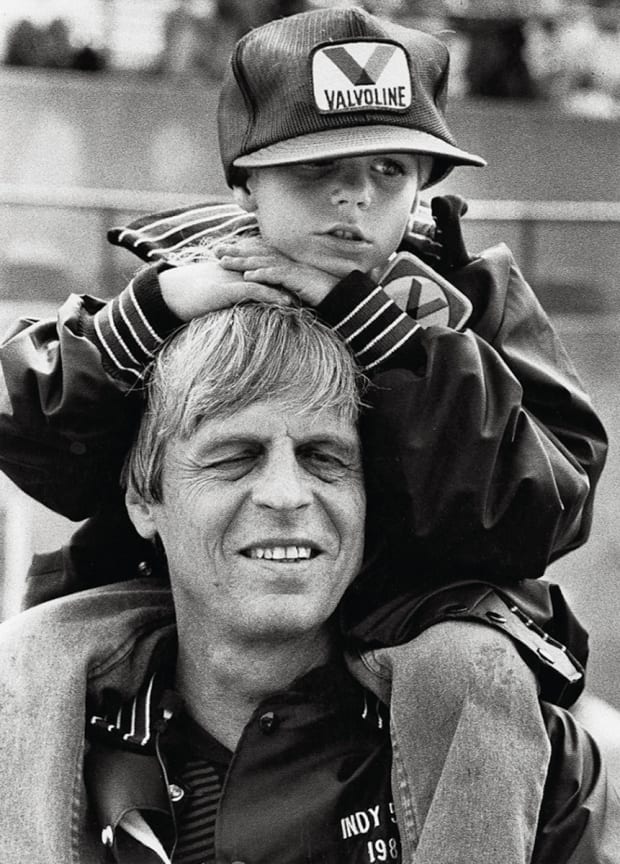

Courtesy of the Plimpton Family

I’m a lucky guy. I can spend all Sunday watching football on TV with my son, and he’s such a fanatic it somehow counts as being a good dad. This is the main reason I thought it wise to bring Ollie to his first game—because he absolutely loves this stuff. In fact, sometimes I think he cares for it all far more than I do, like he’s inherited my passion for sports and multiplied it by 11. (He’s an enthusiastic kid: He multiplies everything by 11.)

And it’s not just watching sports he loves, it’s playing them, too, thank God. Football, basketball, tennis. I know that some parents have to force their kids into the whole thing—but with Ollie it’s not like that. In fact, I’m the one who has to put an end to it: dusk gathering, nearing time for bed, and we’re out on the cracked asphalt road behind his grandma’s house playing an epic five-set match between Ollie Federer and Novak Daddyvic, and the summer night is swooping in and so are bats after our tennis balls in the fading light—bat interference, replay the point. And even though he wants one more rally, one more shot, one more “one more,” he’s only a little boy, and his mother is calling us in for macaroni and cheese.

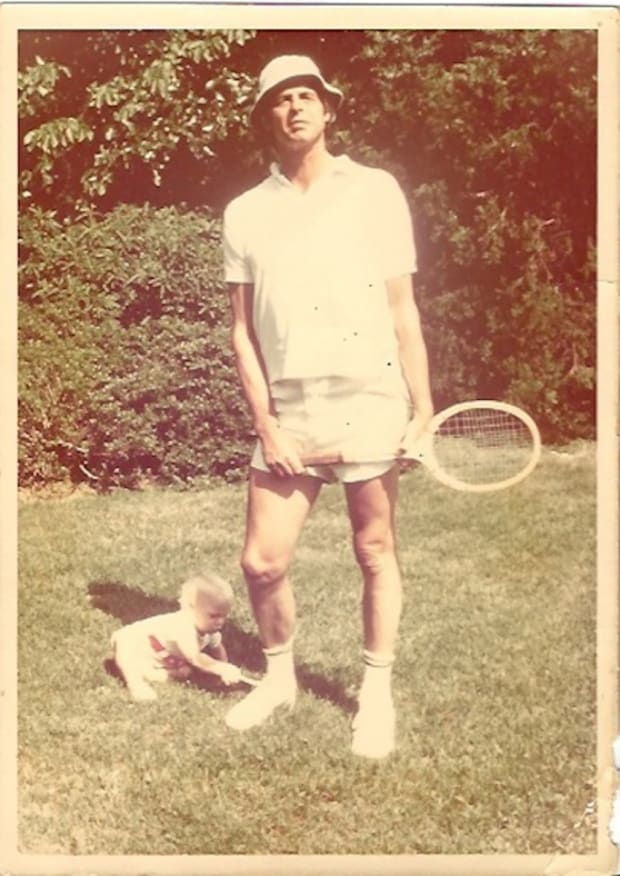

Sports was the biggest connection for me and my dad, George Plimpton, too. It was where we were at our best together—our most comfortable—out there on the court or the field, where not much needed to be said, where love was expressed not through words but through presence. Yes, often absent in so many other ways, when it came to playing sports with me, my dad showed up. We played tennis on the green clay under the summer sun; in winter, floor hockey on the poor hardwoods of our living room; in autumn, touch football in the brown fields behind Peter Matthiessen’s house, the most literary game you could imagine—Jim Salter out there, John Irving at times, Joe Fox, the great editor, Peter and my pops and little me, Ollie’s age, in the middle of the huddle, peering up into the forests of all those nostrils, dripping in the cold.

We watched sports on TV, too, my dad and I—Thanksgiving Lions games, or the Celtics, or the Bruins—often on the little screen in his office, which always seemed to have a game on it, even (especially?) when he was at work writing. These were my father’s teams, literally—as a participatory journalist, George Plimpton had actually played for them to write about the experiences—and so they were now unreservedly my teams. There was a certain familiarity about watching sports together on the tube, a welcome ease. You could somehow be doing something together without really having to do anything at all. It is this way with Ollie, too. We turn on the TV to watch a team we both love, and though he’s often bouncing on the couch or on the carpet tossing around his battered Nerf foot-

ball, there are moments Ollie calms and settles next to me and rests his head on my shoulder, and we simply watch the game. And these moments are quiet little heavens.

My father took me to see live sports, too—and in a manner I’m aware I will never be able to match, what with all his seemingly infinite connections. It was another way he could be a good dad, and he did it so willingly, and with such love. Back then, I loved football and basketball, too, but winning Wimbledon was my dream, and, as good fathers do, he fed the passion with great willingness. One of his good friends was Gene Scott, the Davis Cup player and editor of Tennis Week, and so the U.S. Open was a given every year, as was the year-end Masters at Madison Square Garden, the top eight players in the world battling it out. I remember meeting Boris Becker, my hero, at MSG after a loss. He was a giant, hulking even in defeat, and he was sitting on the locker room bench in his underwear, and he said hello kindly in his soft German accent.

Yes, my dad took me to see tennis and basketball and hockey—he even brought me to the Indianapolis 500 one time—but for some strange reason, in all those years, we never made it to a Lions game.

Courtesy of the Plimpton Family

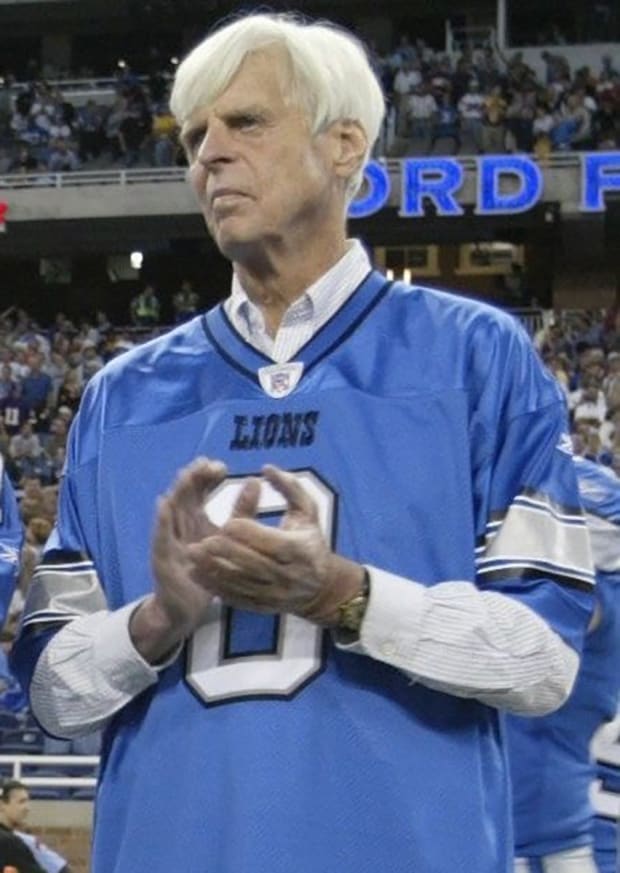

Julian H. Gonzalez/Detroit Free Press/USA Today Network

The name of this piece is a nod to a charming essay my father wrote about bringing my sister to the annual Harvard-Yale football game. It was called “Medora Goes to the Game,” and in it, my dad worries his young daughter would cheer on Yale (blue was her favorite color) rather than his crimson alma mater. In bringing Ollie to see the Lions at MetLife, my concern is the opposite—that he will root for our team too much. Ollie is a devoted fanatic. If he were old enough, I could very easily see him being one of those guys in the crowd with their faces and bare chests smothered in blue paint in 30-degree weather, their crowns topped with a lion’s mane of synthetic fur. (As is, Ollie’s got on a Lions winter hat, and a D’Andre Swift jersey, No. 32, fits snugly over his puffy down coat—he’s well on his way.)

If the Lions lose, will Ollie have a giant tantrum? Will I have to carry him kicking and screaming from the stadium? These are distinct and terrifying possibilities. Even if our team somehow wins, other issues loom. Indeed, when things are going Detroit’s way at MetLife, there are times Ollie actually turns around and starts taunting the massive Jets fan—wagging his finger at him in an “in your face” kind of way. Fearing for both of our lives, I do my best to temper his celebrations—that is, of course, when I’m not leaping up and down like a maniac myself.

Where does this come from, my little guy’s obsession? I remember a few years ago, Ollie, my wife, Lizzy, and I took her dad, Kevin, out to a pizza dinner for the old man’s birthday, and in the car on the way over I was telling Kevin about how wild a Lions fan Ollie had become—way more than me, I explained, he’s really kind of out of control—and then we parked the car and got out and I put on my striped blue Detroit Lions winter hat and Ollie put on his striped blue Detroit Lions winter hat, and Kevin looked at us both and said, “Wait a second, here! I see what’s happened!” And we all burst out laughing, because it was just so clear.

That was the last time we all saw him together, Ollie’s grandpa—later that spring he would die from COVID-19—so I just want to say right here that I admit it, Kevin, you called me on it, and you were right: Ollie’s football fanaticism is my doing and no one else’s.

Yes, it’s my fault, I admit it—but then again, I wasn’t the one who taught Ollie, upon any small victory, to flex his biceps in that strongman pose and shout, “Let’s go!!!”—a deafening exclamation, terrible to behold. Me, I’ve always prided myself on being humble—Ollie, not so much. Instead, Kong-like, he jumps up and down, pounds his chest, roars. It is alarming indeed to see a little boy do this, but when his models are professional football players, what do you expect?

Still, which one of these athletes, I ask you, taught him to do the little nanny-nanny-boo-boo victory dance he performed that one evening after beating me at Connect 4? The truth is, his competitiveness and penchant for celebrating with great fervor is not just imitation, but also who he naturally is. Ollie is built for this stuff—loud, passionate, loves winning, hates losing. For him, everything is a competition, or he’d rather not bother. Who will win the race to the bathroom to brush teeth? Who can get their socks and shoes on first?

And if, God forbid, Ollie (or whichever team he’s rooting for) doesn’t win, the forecast is indeed a stormy one. He cries when his team gets second place in the relay race at the end of Dad’s club basketball. He cries when we have a family race up the stairs to put him to bed and our dog crosses the threshold before him. “It’s not fair!” he screams. (He’s big on injustice, no matter how minor.) I point out to Ollie that pro players don’t cry when they lose (at least, not usually) and they don’t throw tantrums (though actually they sometimes kind of do). Anyway, Ollie’s only 7, and he remains a work in progress, like us all.

Me, there are times I get extremely depressed when the Lions lose (and historically the Lions lose a lot). I take it so personally—I don’t know why. Maybe it’s the way sports teams can become like surrogate selves, the ones we wish we could have been. We pour our battered hopes into them, yesterday’s almost-forgotten dreams. If they succeed, so do we. If they fail, in your gut you feel sick, like life has failed you, and like you have failed at life. I remember one game specifically. It was against Dallas in 2015, the Lions were up 14–0 after the first quarter, and they were finally going to win a playoff game, their first since 1991. And then they didn’t. I was devastated. I went out to dinner that night with my wife—she was newly pregnant with Ollie—and sulked like a ruined and petulant child. Poor Lizzy: I feel so bad for her when it comes to these manic-depressive Sundays, the way she never knows whether her husband (and now her son) will be beaming sunshine or emitting stink lines.

My dad was better than me at handling loss, I think. He, too, was fiercely competitive—he did not like to lose, nor did he like his teams to lose—but he’d developed rather charming ways of expressing his disappointment. He’d perfected a groan he reserved for the Lions—and for moments of extreme exasperation on the tennis court—a kind of high-pitched “Aghhhh!” that you would expect to emerge from an alarmed mountain goat, rather than from his distinguished gray features. And these little cries of anguish, there was the strangest hint of pleasure in them, too, reflecting his wisdom that these were, after all, games—things to be played at—as was life.

“How are the Lions this year, Dad?” I asked him, only a few days before he died. “Aaaaghhhh! They’re just awful, Taylor!” he exclaimed with a kind of relish. He’d just returned from being honored at Ford Field for the 40th anniversary of the 1963 team he’d played with and written about in Paper Lion, and there’s this wonderful photo of him there—he’d received a standing ovation, and with a grin of great pride, he’d raised his hat to the crowd—and every time I see that photo, it breaks my heart. Not just because of how old he seems, his ghost-white hair and hollow face, but the simple, childlike delight beaming forth. (This delight, a kind of shining mischief, is something of my dad’s I recognize so clearly in my son.)

Ollie himself was around 4 when he began to develop coping mechanisms for the inevitable loss involved in being a Lions fan. Most crucially, he invented a game called “pretend football”: Two little matchbox cars represented the opposing teams, which battled each other ferociously, bashing up against each other with metal clacks. “The pretend Lions scored a touchdown, Daddy!” he would announce, proudly.

Over the years, these games have evolved—now, instead of matchbox cars, he runs across the living room tossing a chewed-up Nerf football back and forth to himself, and almost every team in the NFL contends with one another, instead of always just the Lions. The current games have become extremely complicated, too, complete with playoff draws, challenges, slow-motion instant replays and injuries. “There’s another man down on the field, Daddy: Will you look up who the third-string quarterback for the Chargers is?” Ollie’s developed a real Rain Man element to his love of sports, his knowledge of players and statistics now far exceeding mine: “You know who Duvernay is?” he asks me, referring to a wide receiver on the Ravens I have, in fact, never heard of—“he’s dangerous, Daddy, dangerous.” And while his expertise is at times accompanied by a certain arrogance—“do you even know what a ‘jet sweep’ is, Daddy?”—I appreciate that his passion for sports has engaged not just his body but his brain. And I also appreciate the flawless logic of his imagined games—the way the team he wants to emerge victorious always does, and in dramatic fashion, too: with last-second Hail Marys, blocked field goals returned for touchdowns, pick-sixes and so on.

I don’t know, maybe it’s because his pretend Lions are so unbeatable, but Ollie seems to have a far better handle on the real Lions losing than I do. The week after the Jets game, it was Christmas Eve, and Ollie and I were hoping for another miracle, but it wasn’t to be. Instead, the Lions lost (badly) to the Panthers, a critical game that made their playoff hopes dim indeed. Truly dejected, I turned to Ollie and said, “I’m sorry they lost, buddy.” “It’s O.K., Daddy,” my son replied, forever surprising me, and gave me a hug. And all was well in the world.

Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

Dick Raphael/Sports Illustrated

Herb Scharfman/Sports Illustrated

Every night before Ollie finally goes to sleep, his last waking demand is, “Tell me the scores.” This inevitably involves relaying not only scores, but also individual player stats—how’s Tatum doing, and what about Jaylen Brown, and how many yards has Mahomes thrown for?

In the morning, first thing, it’s more of the same: Ollie goes and gets my laptop and climbs into bed with us, and we look at the results. Actually, before he even opens the laptop, he wants to know what happened; he simply can’t wait. So it was in early January when he asked, innocently, “Who won between the Bengals and Bills?” I had lost sleep wondering what I would tell him. “They didn’t finish the game, buddy. Someone got really hurt on the field, and they canceled it.” “What?!” he said, incredulous. To not finish a game seemed unimaginable to him.

Later that day, after school, we talked more about it. I explained to him how everyone was on the same page, the players, the coaches, the announcers, everyone: When it came down to the really important stuff, the game didn’t matter anymore, not even a little. All that mattered was Damar Hamlin, a young human being whose life was on the line. “When it comes to someone maybe dying, there are very few games that do matter,” I explained to him, though I realized as I said it that, in this light, there were actually no games that mattered. “What about the Super Bowl?” Ollie asked, and I replied, “Nope, not even the Super Bowl.” And Ollie got it. He really did. It’s reassuring to know that my little fanatic has a sense of perspective, and that, when it gets right down to it, so does most everyone else. People can be so surprising, sometimes, so wise.

And of course it’s not just sports that lose meaning in the face of life and death—it’s almost everything. How does your office job hold up, or that argument you had with your spouse? In this harsh light, what on Earth does matter?

There’s a weird thing that can happen when you reach the conclusion that nothing matters, though, because then all of a sudden, realizing life to be so precious—everything matters. And for me, at least, this very much includes sports. The way it can bring people together—families, friends, fathers and sons. After all, spending time with your child sitting on the couch and watching a game of football or playing catch in the yard—these are the ordinary, everyday moments that mean something.

There are important moments that happen out there on the field or the court, too, model behaviors I can point out to Ollie and say, “Look at that.” I think of the way Rafael Nadal gives himself so completely to every point, as if it were his last. I think of the way opponents will hug after a game, all animosity forgotten; the way basketball players touch hands with their teammates after their first free throw whether they sink it or not; the way football players kneel and bow their heads to honor a comrade who’s been injured, and to pray . . .

So much else of what’s admirable in sports is invisible, or at least too easily overlooked. Like, for instance, the impossibly hard work and dedication athletes put in. There’s this notion, so prevalent in the weekend warrior’s unconscious, that it could somehow be us out there. It is the daydream of eager children and fat men on couches alike (e.g., Ollie and me): I could have thrown that pass, I could have made that layup, I could win Wimbledon.

Interestingly, part of what my father’s experiment in participatory journalism proved was how far off these fantasies really are. His presence out there showed exactly what would happen if you or I found ourselves on the field—we’d get pummeled. (In his one set of downs quarterbacking for the Lions in a scrimmage, he lost some 30 yards). There was a huge chasm between the professional and the fan, and it wasn’t just the size of these guys, or their athleticism, but the work—the years of practice, of sacrifice. It’s easy to sort of assume such mastery can be attained overnight—the grace of true skill is that it looks so easy—but really it takes a life. Yes, even before football almost killed Damar Hamlin, he’d already given the game his life. And this is admirable, of course. This is the devotion, the love, it takes to master any craft. But it is also just sort of sad.

Does the game matter to these young men? More than anything, perhaps.

“Did we win?” The innocent question, heartbreaking, of the man whose heart had stopped on the field.

Courtesy of the Plimpton Family

Courtesy of the Plimpton Family

Do you want to know what true love is? It’s my dad, bringing me to a Celtics-76ers playoff game when I was Ollie’s age, 6 or 7, in Philadelphia, and when the crowd began to roar and my ears started to hurt—they hurt so much I cried—my dad took me home. There we were at a playoff game of his beloved Celtics, the team he’d played for and whose 1969 NBA championship watch adorned his wrist as a constant, but none of that mattered. The crowd was too loud, and his son’s ears hurt, and that was that.

In the end, it’s all my dad’s fault. My love for the Lions, for the Celtics, for tennis, for sports. I owe it all to him: the Sunday agony, the occasional elation. I owe this particular bond with Ollie to him, too—after all, when it came to sports, he’s the one who showed me how to be a dad. And the same-old tender conversation that began so long ago with him—the physical one of gratifyingly few words—it continues with Ollie today, almost like I’m some sort of conduit, my father and son communicating, connecting, through me. How I wish they could have met for real, though. I wish they’d had a chance to talk sports, to play catch. They would have adored each other. Of each other, they would have been so proud.

He would have been a good grandpa, I think: doting, silly, brimming with mischief and tall tales. My dad was 6' 4". Ollie would have looked up to him with such awe. I remember this feeling—to little me, my dad was a being of heroic proportions. This is the way it is down on the field, too. Thanks to the Lions’ organization and to my pops (somehow still giving gifts 20 years after his death), Ollie and I have been blessed with pregame field passes at MetLife and are watching his heroes warm up from the sidelines. Goff is out there, Swift, Hutchinson, St. Brown. Outsized, impossible, right there. Jeff Okudah catches a pass, taps his feet in bounds before stepping out right in front of us. For Ollie, and yes, for me, too, it is all awe. The size of the players, the skill, the presence of them, so close. The size of the stadium, too, rising up all around us, as if we are at the center of it, and of the universe. Two referees pass by and give Ollie fist bumps. And then, as the Lions conclude their warmups, Antwaan Randle El, former player and the Lions’ current wide receivers coach, jogs over and hands Ollie a practice ball, one of the ones they’d just been playing with. “No way,” I say. “Thank you!” Ollie himself is speechless. He hugs it tightly, so thrilled he’s become shy.

My wife reminds me sometimes that the reason Ollie loves all this stuff so much is not just because he loves the sports themselves, but because he loves me. More than the extraordinary athleticism on display, or the thrill of competition, or even the elation of victory, what it’s really all about to Ollie is that he gets to spend time with his daddy. The simple, sweet fact of this breaks my heart. It’s such an honor, and such a responsibility. For some strange reason, this little creature wants nothing more than to play with me, his greatest hero, beloved somehow even more than Jayson Tatum or Amon-Ra St. Brown, the Lions’ wide receiver named after the Egyptian god of all creation.

And of course, it will not last—Ollie’s time will not always be so devoted to me. I remember how it shifted with my dad when I was in high school: He’d want to play tennis, and I’d want to go do other things, meet up with friends, chase girls, get high. What I wouldn’t give to play a game of tennis with him today.

We head up to our seats. I’d splurged for good ones. Twenty-yard line, 11 rows up. Except for husband-and-wife Lions fans to our right, we’re surrounded by Jets supporters. So that he can see, Ollie stands up on his seat, and I hang on to the back of him, clutching a fistful of Swift’s No. 32 jersey and the puffy coat beneath so that my son will not topple forward. I’d been worried about his fanatic presence there being a potential embarrassment, but of course, even the most outlandish fans are swallowed up by the size of a stadium like MetLife—even his little taunts toward the big guy behind us dissipate into the din and madness, forgotten as soon as they occur. In other words, this is the exact place for a big personality like Ollie’s—he can be as excited as he wants to be, loud and full of passion and opinion, and he’ll just be doing exactly what he’s supposed to be doing. And the truth is, all game long, he’s the perfect little kid. He does little dances when the music comes on during TV commercial breaks; he jumps up and down and roars Let’s go!!! when the Lions get a first down or a sack. In quieter moments, he looks around at the grand spectacle of it all, at home, his face all lit up with wonder.

I can’t tell you how much he reminds me of my dad sometimes. The beanstalk body, the intense curiosity, the luminous love of life. The delight. It’s like there’s this wonderful confusion of identity and space and time, and I do not know who is who anymore—is it now, is it then, am I father or son, and is my son somehow my dad, and my dad, so long gone, is he really gone? Indeed, there are moments at MetLife when I cannot help but sense my father’s presence—as if all these years later he’s finally managed to take me to my first Lions game, and that he’s somewhere up in that Honolulu-blue sky with its perfect little puffy white clouds, grinning down at us proudly—but of course, the truth is he’s much closer than that. He’s standing right next to me, I’ve got a clutch of his jersey and jacket in my fist, and I’m hanging on tight so he will not fall.