The Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial satellite, in 1957, forever changing history.

The satellite remained in orbit until January 1958. It provided valuable data on atmospheric density and served as a crucial test for future space technologies.

Nearly seven decades later, satellites have become an integral part of our daily lives, powering global positioning systems (GPS), providing weather forecasting, and monitoring climate change.

Their multiple applications have drawn interest from private companies and public administrations that are interested in building policies and technologies from satellite data.

The European Union, for instance, has Copernicus, the largest Earth observation programme in the world.

Led by the European Commission in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), Copernicus was established in 2014 and now provides freely accessible data.

But how does Earth observation really work? And what challenges can it help us solve? To answer these questions, Euronews Tech Talks spoke with Jean-Christophe Gros, the EU programme coordinator at the European Space Agency (ESA).

What is Earth observation?

Earth observation is the practice of studying our planet from space using satellites, which can be launched both in Earth's orbit and in polar orbit.

Gros explained that Earth observation relies on various techniques. These include radar satellites, which can see through the clouds and operate at night; optical satellites, which capture high-resolution images of the Earth’s surface; and satellites with spectrometers, which are crucial for atmospheric monitoring.

All these technologies are key to looking at the Earth from a different perspective and can help us address the most pressing challenges of our time.

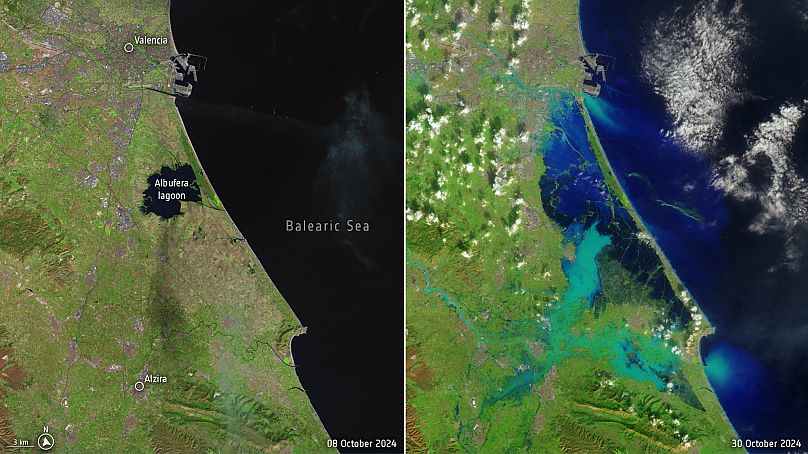

For instance, satellite imagery can monitor rising sea levels and predict and track floods, landslides and wildfires.

“We are also doing a lot of monitoring in terms of (...) the concrete impact on populations. Where to build a city, where not to build a city, if we can anticipate that this part of the map will be flooded or not,” Gros said.

Earth observation and greenhouse gas emissions

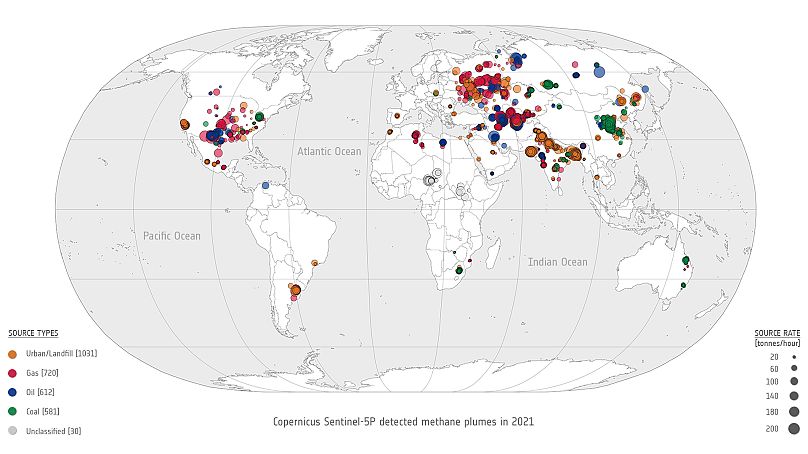

Earth observation also plays a role in detecting greenhouse gases, gases that absorb Earth's radiation and reflect it back, contributing to the rise in global temperatures.

Methane is one of these gases. Colourless and odourless, it is produced by both natural and human activities, and it accounts for around 30% of the rise in global temperatures since the Industrial Revolution.

Experts say satellites can help to spot methane leaks.

For instance, in March 2023, Emily Dowd spotted a methane leak in the area of Cheltenham, in the United Kingdom. The then PhD researcher was observing a landfill near the town via a GhGSat satellite when she noticed the leak, which came from a factory.

“(Methane) has a 20-year global warming potential, which is 82 times greater than carbon dioxide. Being able to find gas leaks or leaks of methane is important for reducing human impact on climate change,” Dowd told Euronews Next.

To identify the methane leak, Dowd used GHGSat, a constellation of satellites of a Canadian data company capable of detecting methane with a high spatial resolution of 25 metres.

GhGSat receives data from other satellites like Copernicus’ Sentinel 5P, designed to monitor a wide range of gases on a global scale.

On top of methane, ESA is working on its mission to monitor and track carbon dioxide with the project CO2M.

CO2M is planned as a three-satellite mission to measure the greenhouse gas with very detailed images, and its first satellite is expected to be launched in 2025.