They were known as “the McDonogh Three,” and unlike many stories of the tumultuous civil rights era, this one has a hopeful ending.

On May 4, 2022, Leona Tate, Gail Etienne and Tessie Prevost are scheduled to cut the ribbons around the front door of the former McDonogh 19 Elementary School.

Located in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward, the school was the scene of some of the nation’s fiercest anti-integration school battles in the early 1960s.

At the time, Tate, Etienne and Prevost were 6-year-old Black girls who wanted to attend first grade.

White protesters, mostly women, heckled and spat and shouted racist slurs at them as they tried to enter the school. Threats of violence were intense, and when local police could not keep the peace, federal marshals were called in.

Now named after the three women, the school has been transformed into the TEP Center, whose name consists of the first letters of each woman’s last name. It has been redesigned to include affordable housing and exhibition space focused on the civil rights era and the three women’s stories.

As co-author of “William Frantz Public School: A Story of Race, Resistance, Resiliency, and Recovery in New Orleans” I, along with research colleagues Meg White and Martha Viator, spent four years combing through archives researching school desegregation in New Orleans.

What we learned is that the story of the McDonogh Three has been mostly overlooked. But through sheer determination, they were able to restore a building that now bears their names and celebrates their contributions to the civil rights movement.

In our view, their story further challenges society to end the racism that once engulfed a New Orleans community – and still lingers today.

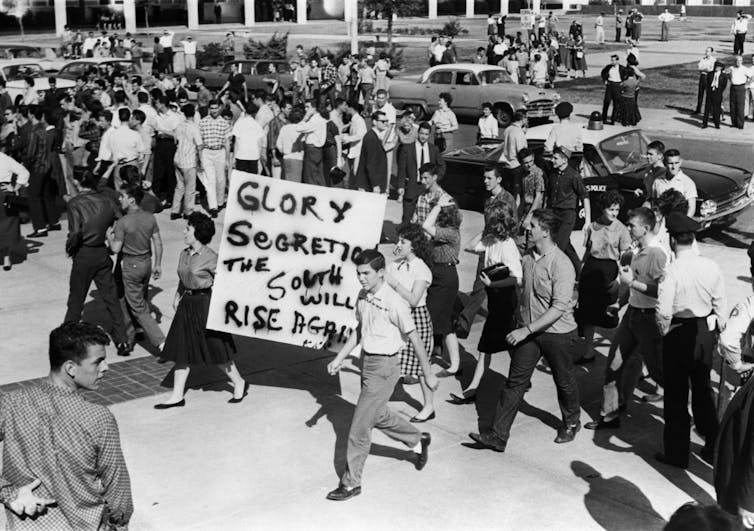

Anti-integrationist protests

The story of the McDonogh Three could not have had an uglier beginning.

In its landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1954 that segregated public schools were unconstitutional. Several Southern states refused to comply and sometimes violently resisted the ruling to desegregate their schools.

Louisiana was one of them. Six years after the Brown decision, protesters vehemently opposed the Orleans Parish School Board’s desegregation plan and targeted the all-white McDonogh 19 school, which the three Black girls aimed to attend.

“I remember riding in the car, coming up to the school, looking out the window and seeing these mobs of people,” Etienne said in an interview. “… I felt like if they could get to me, they’d want to kill me, and I didn’t know why.”

Political resistance to desegregation delayed the girls’ enrollment from September until mid-November. When they finally were permitted to go to classes, protesters still did their best to intimidate them and their families.

Not understanding the intentions of the protesters, one of the girls said in later interviews that they thought the police were there to prevent the cars they were riding in from hurting the bystanders.

“I thought a parade was coming,” Tate recalls before wondering, “And why did I have to go to school on Mardi Gras.”

The girls spent much of that first day sitting in the hallway outside the principal’s office.

In an interview years later, Tate said when they were finally brought to their classroom, white students got up and left.

By the end of their first day, most of the white students had been withdrawn from the school. Within days, all the white students had left McDonogh 19.

The protesters also left, having achieved their goal of preventing white and Black children from attending classes together. The only students were the three Black girls.

But the threat of violence remained, and throughout the school year, U.S. Marshals escorted the girls to and from school.

The three girls at McDonogh were not the only ones requiring armed protection.

During the same time, at the William Frantz Elementary School, Ruby Bridges faced a similar fate when trying to integrate an all-white school. Though Bridges’ story is more widely known, all four girls are credited with desegregating New Orleans Public Schools.

From tragedy to triumph

Named after the wealthy slave owner John McDonogh, the school struggled in the decades following 1960.

White flight from the city of New Orleans and its public schools resulted in a resegregation of the school almost immediately, only this time it became an all-Black school. High rates of poverty and crime affected the surrounding neighborhood in the 1970s and ‘80s.

One sign of progress occurred in the mid-1990s when the school was renamed after jazz legend and New Orleans native Louis Armstrong.

But at the end of the 2004-05 school year, the district decided to close the school, due in part to low test scores and also because inadequate funding had caused the building to fall into significant disrepair.

The facility was further damaged by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, and the Orleans Parish School Board planned to sell the historic building, deeming it too expensive to repair.

The building sat vacant for over 10 years.

Born and raised in the neighborhood, Tate’s roots run deep, as did her connection to the history that happened at McDonogh.

Like Prevost and Etienne, Tate graduated from New Orleans’ public schools. She remained in New Orleans and following Katrina chose to stay in the city despite the mass exodus of many residents.

She never gave up on the Lower 9th Ward, the school building or her commitment to telling the story of events that took place on what she considered the hallowed ground of the school.

In 2009, Tate founded the Leona Tate Foundation for Change. Over the years, the fledgling foundation raised US$725,000 to purchase the building.

Tate also led efforts to place the building on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2016, Tate achieved her goal. The designation formally recognized the contributions of Tate, Etienne and Prevost for their role in the civil rights movement.

Now, Tate’s efforts have transformed the building from an abandoned school to a community anchor.

The building provides a new home for the Lower Ninth Ward Living Museum, which displays photographs and offers oral histories from those who lived in the community during the civil rights and post-Katrina eras.

In addition, the TEP Center provides office space for two community groups. One of them, “Ringing the Bell,” provides support for teachers who want to incorporate the history of the civil rights movement into their curriculum.

The other group, Voices of Resistance and Hope, is a partnership with the National Museum of African American History and Culture that collects contemporary stories of African Americans.

Both Etienne and Prevost praised Tate and her determination.

“I’m just glad that we are being given an opportunity to remind those who have forgotten,” Etienne said. “"That the true and full story gets out there. That’s all we’ve ever wanted, really. Thank God it is finally happening.”

Describing Tate and Etienne as “her sisters for life,” Prevost explained in an interview that she sees the project as a step toward healing larger racial divisions.

“We have to come together and forget all of this foolishness,” Prevost said. “That’s what we need to do.”

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.