While researching this piece, I Googled “best self-help books.” The first result was a Reddit post asking an evergreen question: “Self-help books that ACTUALLY helped you?”

Books on empowerment and self-improvement have been balms for millions of people for more than a century (Self-Help by Samuel Smiles was the second bestselling book of 1859, beat out only by the Bible), and to this day there remains a consistent churn of self-help books for women, filled with authors inspiring readers to focus on success, overcoming imposter syndrome, and living our Best! Authentic! Lives! Though these aims are noble, they’re more mental than physical. Platitudes on matters like confidence and bravery can fly over the heads of people seeking practical, baseline advice on how to get through the day, particularly when simply the tasks of living feel like Sisyphean burdens. But a new generation of self-help books is answering the call for gentle advice, helping readers build true foundations of self-care—literally “how to take care of yourself”—while removing barriers of shame.

The third chapter of KC Davis’s bite-sized How to Keep House While Drowning gives a pithy nod to one of the most well-known self-help books of all time: “Marie Kondo says to tri-fold your underwear.” Of course, there’s much more to Kondo’s seminal work The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up than just her folding method, but it’s the perfect instance of the push and pull between self-help books and helpful tips. Davis explains that not everyone will have the mental or physical energy for the rest of their lives to employ the KonMari method. The same goes for many of the most popular self-care fads. (Davis names a few: “Capsule wardrobes! Rainbow colored organization! Bullet journals!”) It’s hard not to feel like what Davis deems a “self-help reject” when you’re going through a serious downturn in your life—be it a drastic period of life change, a mental health crisis, or several weeks of constant stress due to circumstances out of your control—and can't keep your pens in perfect technicolor formation.

Life is cyclical, and everyone goes through it at some point. (Odds are plenty of constant stress is on the horizon.) Davis went through her own downturn after she welcomed her second baby, when her in-person community support and the safeguards she prepared to ward off postpartum depression swiftly crumbled amidst the 2020 pandemic lockdowns. Her origin story for Drowning even has a more kismet tie to Kondo, who admitted in early 2023 that she relaxed her tidiness standards in her California home after welcoming her third child.

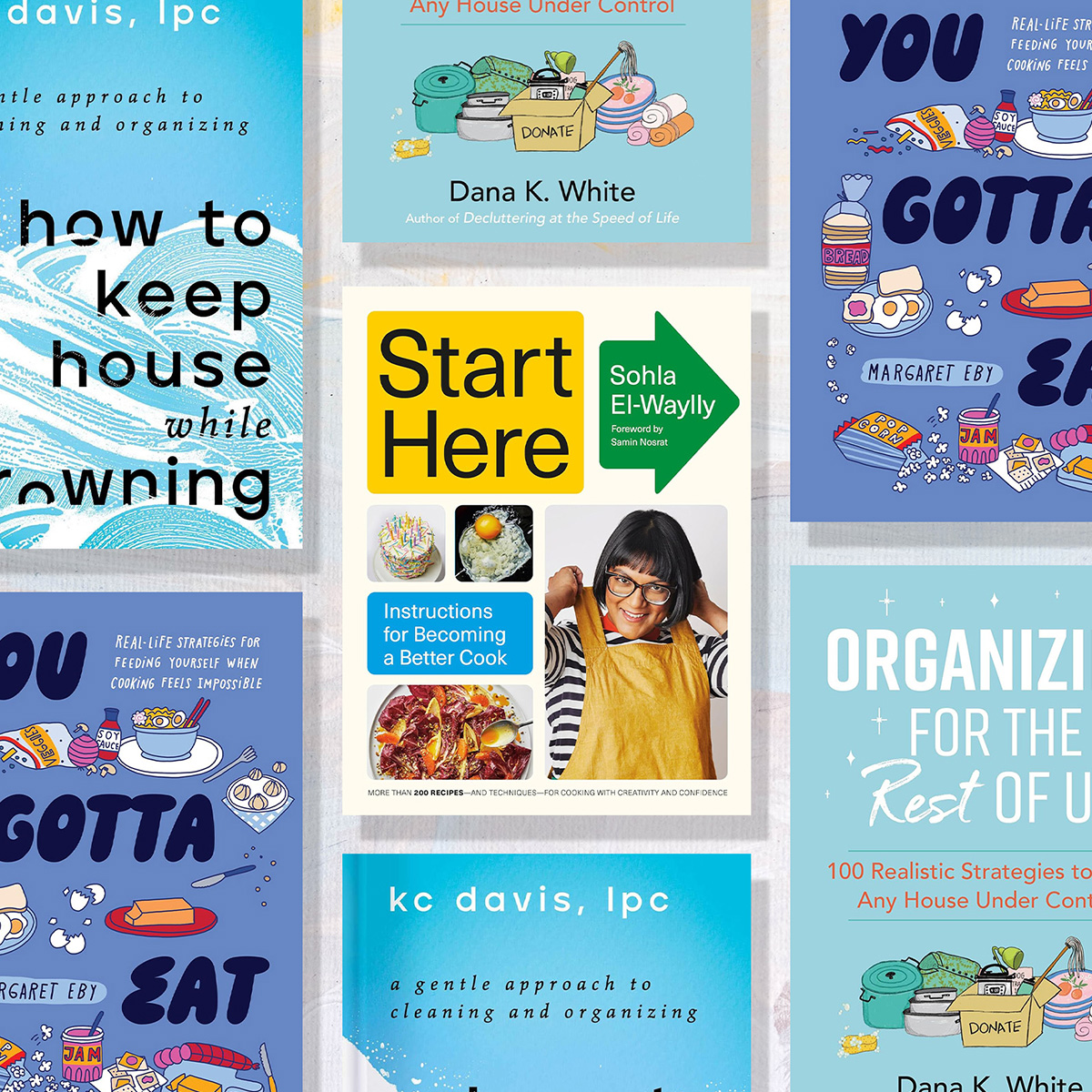

This recent batch of cleaning advice manuals and cookbooks are aimed at meeting readers where they are, teaching us how to cultivate our own skills rather than overhauling our routines to fit a prescribed method or cultural norms.

How to Keep House While Drowning has found a fanbase full of passionate recommenders (myself included) because it’s an advice book that truly speaks to everyone by focusing on a population which often hasn’t felt served by mainstream self-help: neurodivergent people (or “neurospicy” if you prefer). #CleanTok fans who haven’t heard of Drowning may have come across Davis through her viral video on her ADHD fridge, where the Texas-based licensed professional counselor explains how she prioritizes visibility in her fridge, to make sure she never opens the door to be greeted with the stench of rotting vegetables. Davis’s TikTok led me to her book, and I felt surge after surge of recognition as I read through her "struggle-care philosophy" of providing compassionate and nonjudgmental help to people who struggle with everyday tasks like cooking and cleaning. Her book will hold your hand and tell you that chores (or what she calls “care tasks”) are morally neutral. There is no right way or wrong way to complete them, and in an ideal world, we wouldn’t believe that there were.

Both How to Keep House While Drowning and Margaret Eby’s new cookbook You Gotta Eat begin by interrogating the shame that’s baked into even the most baseline decisions of maintaining your body and home. Expectations of cleanliness and good eating habits (even those seen as anti-diet culture) operate off a prescribed morality that the public learns from society and imposes on both themselves and the world around them. (There’s a reason why Drowning includes a chapter dedicated to “critical family members” who offer rude comments in lieu of actual help.) Even a neurotypical person with no chronic mental health issues has likely been in a situation where their home or food choices have been judged, either by themselves or an outside person, as “bad.” For people who aren’t used to cooking or cleaning regularly, changing their habits can seem terrifying, not just because all change is difficult, but because they’ve been conditioned their entire lives that they’ll never be able to achieve the "ideal" home or the "ideal" meal. Both Drowning and You Gotta Eat start by pointing out these internal criticisms and expelling them before encouraging readers to make their everyday care decisions work for them.

And as a food journalist and critic, Eby knows that feeding yourself can carry not only a lot of baggage, but also require a lot of effort. Her book’s title says it all—you have to eat. Even if you love to cook but can’t find the time; even if your depressive spiral has made turning on the oven impossible; even if your history with disordered eating has made you resent the existence of food in general. Speaking with Marie Claire ahead of You Gotta Eat’s mid-November release, Eby describes her goal for You Gotta Eat as presenting a cookbook that’s “so radically baseline.” It features chapters like “Open Something” to “Microwave Something” to “Cook Something.”

“I could have used this when I had my first apartment and was substantially living on chickpeas,” Eby says. “I could have used this like multiple times in my life when I had a hard time with depression or anxiety. This is a book that I hope will help anyone who's like, ‘I would love to cook. I find myself in a rut. I am tired of ordering fast food, or the prepared food aisle of Trader Joe's. I just want to do something else.’”

Platitudes on matters like confidence and bravery can fly over the heads of people seeking practical, baseline advice on how to get through the day, particularly when simply the tasks of living feel like Sisyphean burdens.

Be warned, that “something else” may take some attitude adjustment. You Gotta Eat isn’t filled with recipes so much as combinations. One of the first loose recipes in the book is a canned pineapple and mayo sandwich, and that’s a couple pages after the first of many choose-your-own-adventure sections where Eby encourages you to roll the dice on suggested ingredients for your next bean salad, canapé, smoothie, or casserole. Once you unlock a fear of hitting an unfamiliar flavor combination, there’s a joy in remembering the imaginative fun that can be applied to food. As Eby points out, “There are so many incredibly creative people who have figured out not only how to feed themselves, but also how to produce some amount of creativity or community or joy in this task that's so repetitive that we all have to engage in every single day.”

Of course, not every self-help book can help everyone. But this recent batch of cleaning advice manuals and cookbooks are aimed at meeting readers where they are, teaching us how to cultivate our own skills rather than overhauling our routines to fit a prescribed method or cultural norms.

If You Gotta Eat is the pep talk you need for the base level of feeding yourself, Sohla El-Waylly’s Start Here is the ideal textbook when you’re ready to embark on the next phase of your home-cooking journey. Anyone who’s attempted to teach themselves to cook knows that most food media, from cookbooks, to online recipes, and even instructions in home-meal kits like HelloFresh, assume a certain level of knowledge. Recipes will omit the temperature needed to simmer or forgo explaining the difference between chopping and dicing, as if the reader should already know how to. El-Waylly—who rose to fame on Bon Appétit’s Test Kitchen—explains every technique she uses in her home-cooking tome and includes pictures (because visual aids are often the best way to learn these methods). Not only that, El-Waylly intersperses her lessons with stories of mistakes she’s made over her culinary life to demonstrate that making errors and learning from them are a critical part of becoming a great cook.

Self-proclaimed decluttering expert Dana K. White has written three books on her “reality-based” home care methods—my personal favorite is Organizing for the Rest of Us. Yes, many parts of the book are similar to the popular method that has been established by countless organizational gurus before White, including Kondo: Declutter first, then organize, then establish a cleaning routine. But following KonMari method arguably requires a level of dedication; White, though, recognizes that if you tell someone (like me) to empty everything in their closet into a big pile, I’ll be tripping over that pile for the next week (or more) as I can probably only dedicate an hour a day to it, ultimately feeling like I failed at the task. For people who have talked themselves out of a deep clean based on how monumental the task seems, Organizing assures them that the journey to their ideal state of cleanliness can happen on their own timeline.

It has been over a decade since the term “adulting” entered the public lexicon and was quickly derided. Critics insisted that young people were simply being childish and unable to handle day-to-day tasks, ignoring an unspoken truth that many young people today are entering adulthood without infrastructures in place to teach and learn life skills, like culinary basics or financial literacy.

Not to mention, in recent years we’ve experienced a devastating global pandemic, an exponential rise in social media, a harrowing cost-of-living crisis, and a conservative political movement that’s about to enter its second wave, spurring an epidemic of chronic stress and declining mental health. Amidst all that, several generations have begun to speak out more about the struggles of everyday life, and the conditions, both continual and intermittent, that may cause us to drop the ball on societal standards of self-care. But as Eby points out, “There's always going to be structures that kind of make you feel bad implicitly or explicitly.”

In the tumultuous coming years, books like Eby’s will serve as solace, to help people remember that their body and their corner of the world can be as creative or as calm as they choose. As Eby tells Marie Claire, “There's enough to feel bad about in the world without having it come from inside your kitchen or inside your living room.”