John S. Chase is the Texas architect you wish you knew about—or perhaps should have already heard of. Inspired by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright with his own postmodern twists, Chase’s work has left a mark in East Austin, on the Texas Southern University and University of Texas campuses, and in churches all over the state. Now, a new University of Texas Press book, John S. Chase—The Chase Residence, celebrates Chase’s remarkable 60-year career. The book explores how Chase turned his own Houston home into the centerpiece of a larger body of work through a process that was in “equal measure architectural, social, personal, and political.” This new story of the Chase Residence, still home to Chase’s widow, Drucie, demystifies how Chase fashioned a space to fit his family—and simultaneously fixed his place in architectural history.

John S. Chase was also a trailblazer for architects of color. He entered the University of Texas soon after its desegregation and soon became the first Black person to obtain a master’s degree in architecture. He was also the first state-licensed Black architect in Texas. At one point, Chase served as the first Black president of the Texas Exes, UT’s alumni association. And he was a founding member of the National Organization of Minority Architects.

The Chase Residence was a collective effort. It was written by David Heymann, a professor of architecture at UT, and includes a lengthy essay from co-author Stephen Fox, an architectural historian as well as contributions from architecture students Heymann took on his visits to Chase’s own home in Riverside Terrace, considered a timeless masterpiece among the many houses, churches, and other edifices he built. That group, led by Heymann, tracked down Chase’s own architectural drawings, made new drawings of key details, and persuaded Chase’s family and friends to contribute photos that bring the home’s long history to life. Best viewed at night, the Chase house, even after nearly 70 years, remains a “lantern, a beacon in the city.” It is a “landmark and a landmark accomplishment.”

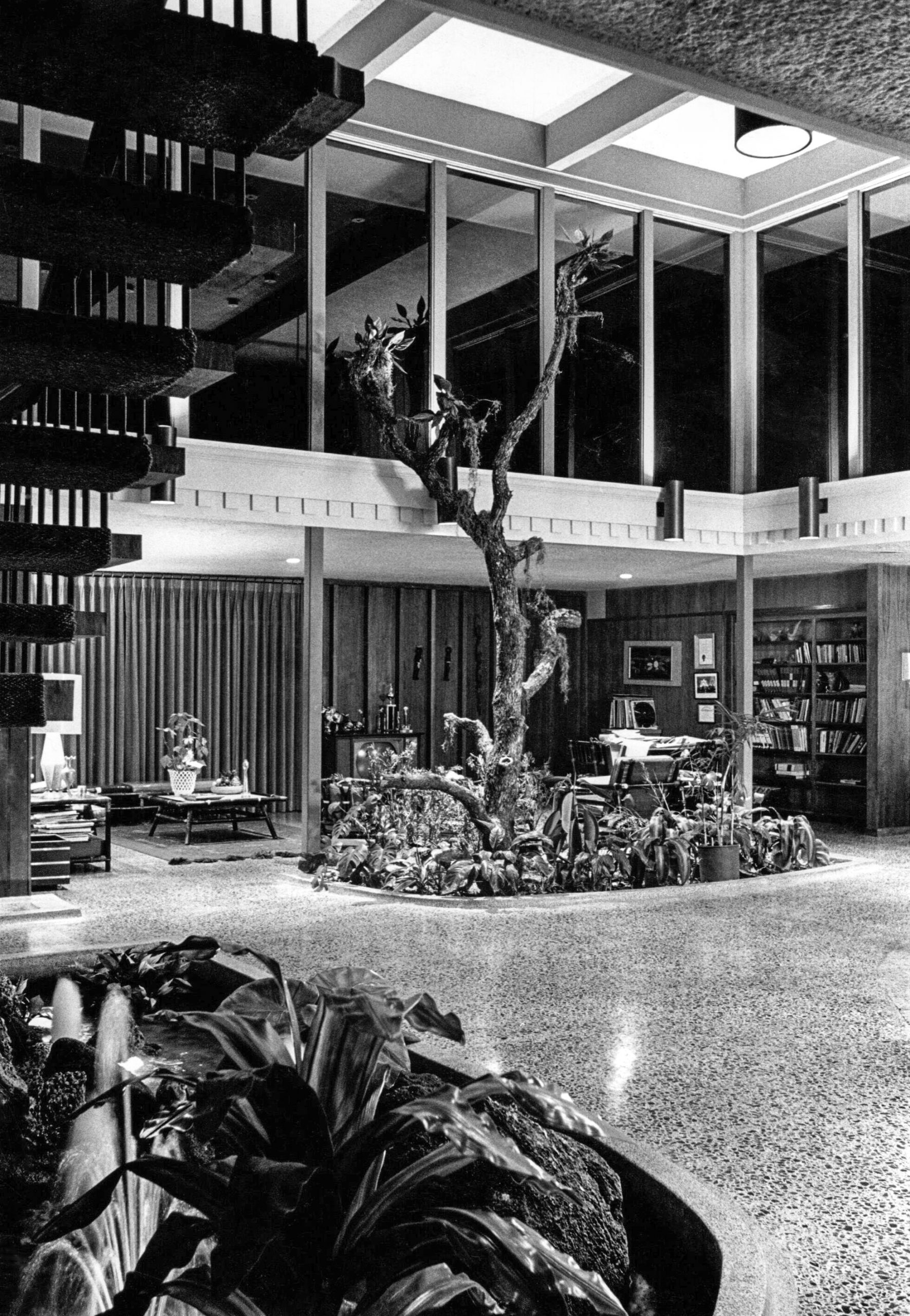

Chase artfully created his house beneath loblolly pines with windows that fully embraced Houston’s humid greenhouse climate. Its vast interior courtyard offered views of leafy tropical plants and gave his boys, John Jr. and Tony, space to ride bikes around a koi pond. The den where Chase worked offered vistas of family life even as he continued to sketch out a fast-growing list of projects for his firm. Inside the original house, Chase tucked a bar behind a bookshelf so that visiting Baptists ministers, teetotalers who frequently commissioned him to build churches, would not spot liquor but could be quickly extracted from an alcove when politico friends arrived for cocktails.

Churches remained a mainstay of Chase’s practice in the 1950s and ’60s, Fox writes. Many churches designed by Chase still stand proudly in Austin, Dallas, and Houston, too. In Houston’s Fifth Ward, Chase built the First Shiloh Baptist Church in 1954 and ’55. The church features a towering brick sanctuary with dramatically rising roof planes and a bell tower, a landmark on Lyons Street fit for a congregation established for more than 100 years. A marker outside the church today marks its historic status and Chase’s contribution, too. Through those early works, Chase had become a “starchitect.”

Gradually, Chase’s other projects took form as other private homes, more churches, and landmark buildings that rose across Texas—and beyond, as Fox’s essay explains. One of his very first jobs in 1952 was a building for a group then known as the Colored Teacher’s Union in Austin. He later earned major commissions from clients like Texas Southern University and Tuskegee University in Alabama. Many of his masterworks still stand on TSU’s Houston campus, including its Humanities Building, with a stunning rounded entrance bay, its student center, and its law school.

Eventually, Chase designed buildings on the campus of his alma mater, too—including UT’s utilitarian San Antonio garage and the track and soccer stadium. But UT wasn’t always good at remembering its famous alumnus. He doesn’t appear in the school yearbook, for example. The first on-campus show featuring his work didn’t occur until after his death in 2012. But recently, one of his early Austin works, the 1952 headquarters for the teacher’s union, was acquired by UT. It’s now being remodeled and refitted as part of the university’s community engagement programs—in a way, taking Chase’s architectural journey full circle. There’s also a John S. Chase scholarship fund at UT for promising Black students, particularly those with an interest in architecture. And now, at long last, there’s a UT Press book honoring his legacy and his home.

As his clientele and family expanded into the 1960s, so did the Chase residence. The Chases welcomed their third child, Saundria, to the family. In 1968, when she was six, he began a renovation and simultaneously enclosed the atrium to create a vast two-story gathering space for a who’s-who of famous friends and clients, including the late Congressman Mickey Leland, actor Gregory Peck who was in town for a Democratic fundraiser, and other luminaries like John Connally, then governor of Texas. One iconic photo shows Leland, a regular at the Chase home, lounging in that atrium with Saundria, by then a young adult. The Chase house, “always in a state of flux,” continued to evolve. This new book, as Fox writes, honors an architect who was part of a larger artistic movement that “powerfully imagined, and gave compelling form to, new ways for African Americans to live in the American South, with dignity, assurance and distinctive modern style,” too.

Read more from the Observer:

-

The Blacklist: Screened out by automated background checks, tenants who face eviction can be denied housing for years to come.

-

Federal Regulators Have Fast-Tracked Review of Disinfectants That Claim to Kill COVID-19: How one Texas company with no previous experience in the industry has seized a pandemic-sized opportunity.

-

The Long, Winding Road that Led to the SBOE’s Decision for Texas Schools to Teach Abstinence-Plus Sex Education: For the first time in 23 years, the State Board of Education has updated the state’s health and sex education standards for middle schoolers. The board voted to expand what students learn about safe sex, but LGBTQ2+ issues and consent are still nowhere to be found.