The unexpected surge of solar activity during the ongoing solar maximum may be tied to a lesser-known, 100-year-long cycle that is just beginning to ramp up again, a new study suggests.

If that's true, the next few decades could see further increases in solar activity that may threaten Earth-orbiting spacecraft and continue to trigger vibrant auroras across the globe. However, other experts are skeptical of the new findings.

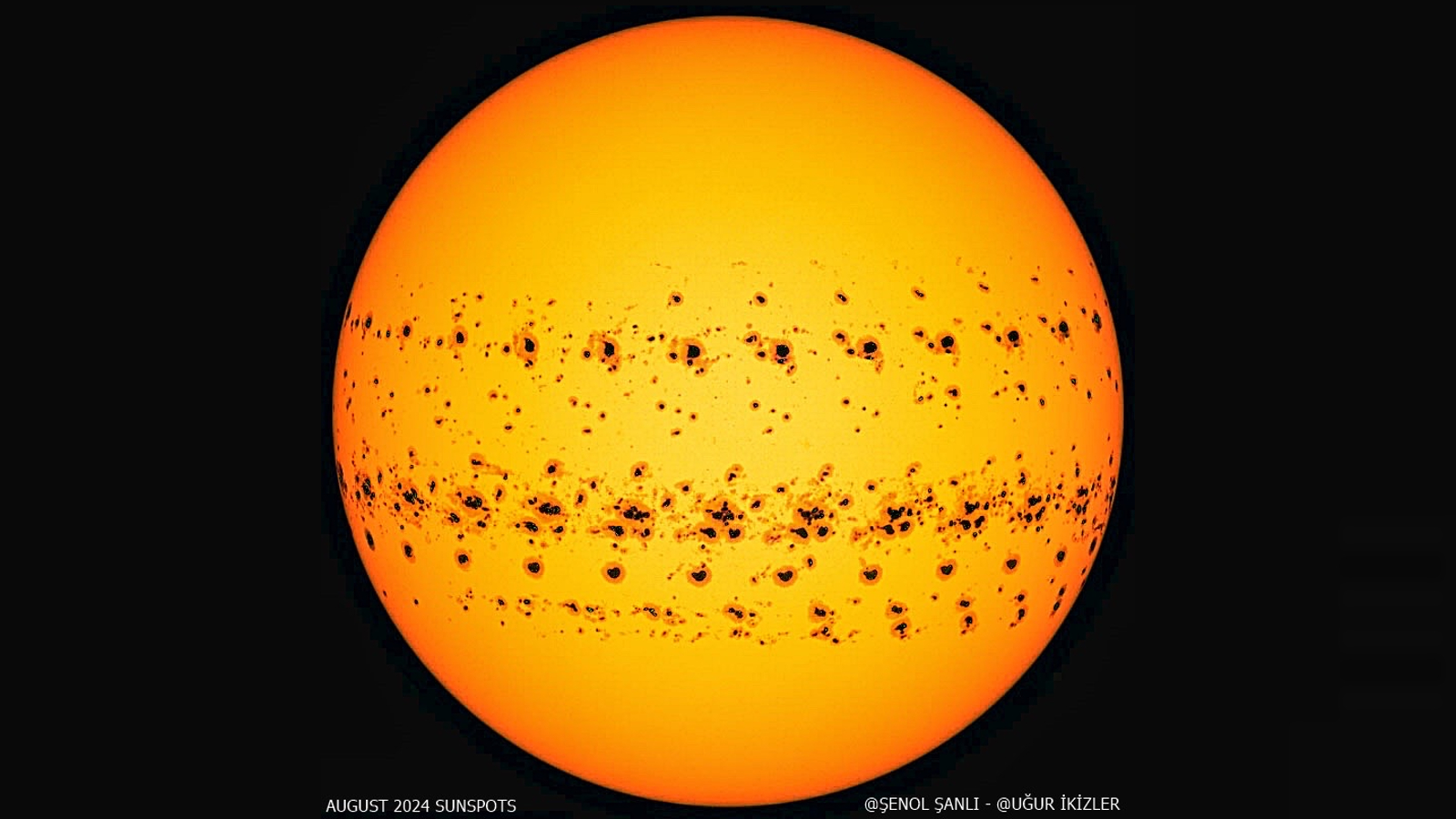

Solar activity naturally waxes and wanes throughout the solar cycle — a roughly 11-year period in which our home star goes from being mostly calm in a phase called solar minimum to being a chaotic mass that frequently spits out powerful solar storms at solar maximum, and back again. This cycle is also known as the "sunspot cycle" because the number of dark patches on the sun rises and falls due to changes in the sun's magnetic field, which completely flips during solar maximum.

However, there are several other cycles that dictate solar activity. One example is the Hale cycle, which governs how individual magnetic bands move across the sun's surface and has recently been shown to influence the progression of the sunspot cycle. Historical records also show that the sun has experienced several long-term fluctuations in solar activity over the past few millennia. These included the Maunder Minimum — a period of greatly reduced solar activity between 1645 and 1715.

Another, lesser-known repeating pattern in solar activity is the Centennial Gleissberg Cycle (CGC) — a variation in the intensity of sunspot cycles that rises and falls every 80 to 100 years. The CGC is still poorly understood, but it is likely tied to "subtle sloshing" of the magnetic fields in each of the sun's two hemispheres that slightly alters the Hale cycle, Scott McIntosh, a solar physicist at the newly formed space weather solutions company Lynker Space, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Related: 10 supercharged solar storms that blew us away in 2024

In the new study, published March 2 in the journal Space Weather, researchers suggest that the CGC might have just "turned over," or started again. This could also explain why the ongoing solar maximum, which officially began in early 2024, has ended up being much harder to predict than initially expected.

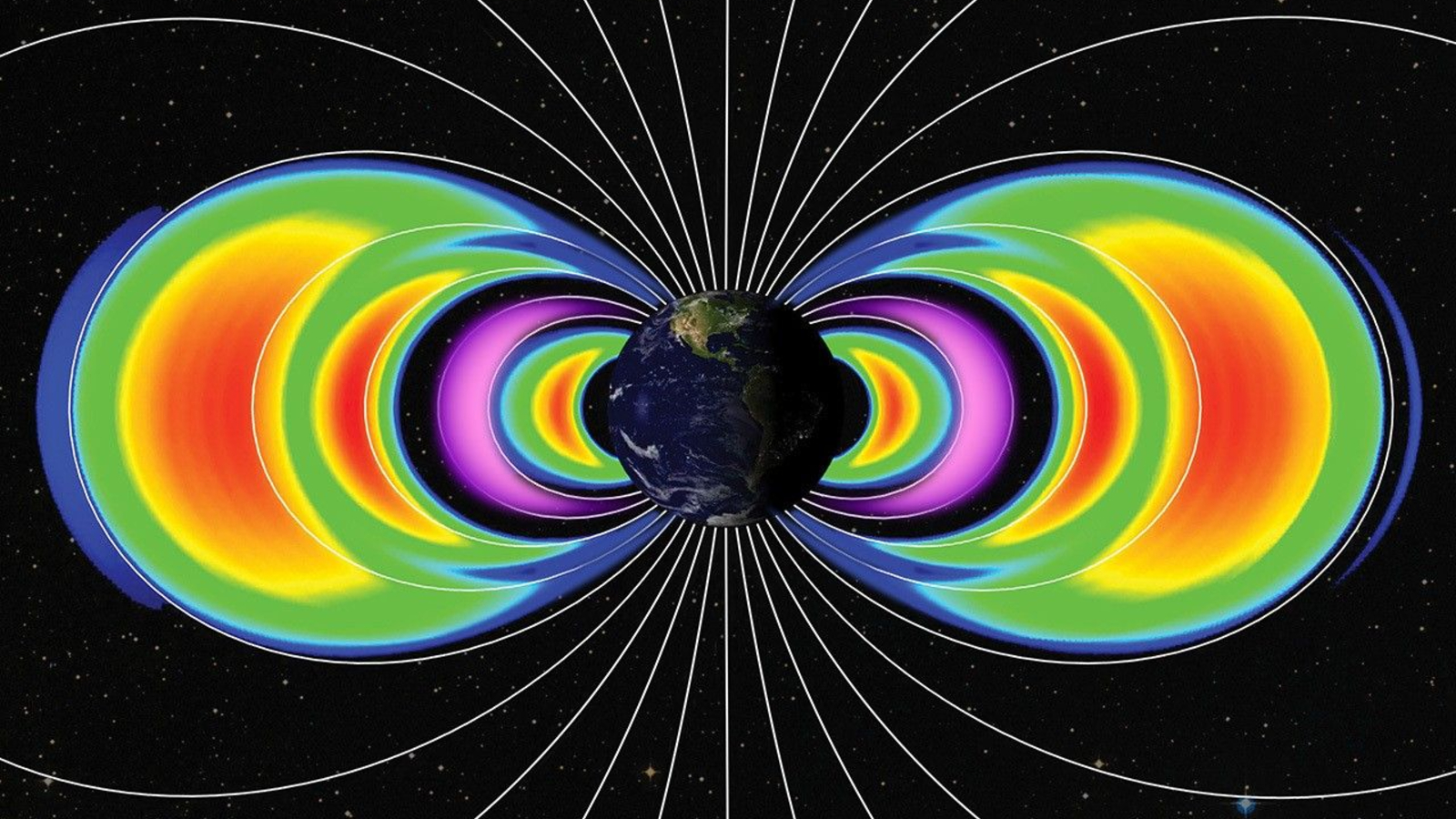

The study team came to this conclusion after analyzing changes to the "proton flux," or number of positively charged particles, in Earth's inner radiation belt — the first of two doughnut-shaped bands of charged particles surrounding our planet. Collectively, these bands are known as the Van Allen belts.

The inner belt's proton flux decreases when solar activity increases because of interactions with Earth's upper atmosphere, which swells as it soaks up more solar radiation. On the flip side, the proton flux increases as solar activity decreases.

The new analysis shows that the flux increased over the past 20 years but has just started decreasing over the past year or so. This suggests that we have "just passed the CGC minimum" and that average solar activity will start to rise again, study lead author Kalvyn Adams, an undergraduate researcher at JILA, a joint institute of the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, told Live Science.

The proton flux data were collected by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellites as they passed through the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) — a mysterious dent in Earth's magnetic field above South America and the South Atlantic Ocean where our planet's protective shield is the weakest. This was a key reason these trends became apparent, the researchers said.

"The SAA is a region where the Earth's magnetic field is weak and allows trapped protons to reach lower altitudes," Adams said. This allows the NOAA spacecraft to "see into" the inner radiation belt without having to fly directly into it, which would be extremely tricky, he added.

Surprising solar activity

We may be nearing the end of the maximum phase of the current sunspot cycle, Solar Cycle 25 (SC25). This peak has been very active and has included some extreme space weather events, such as a supercharged geomagnetic storm in May 2024 that triggered some of the most widespread auroras in the past 500 years. However, this flourish of activity was not initially expected.

During the previous sunspot cycle, SC24, the sun was surprisingly quiet throughout solar maximum. This led space weather experts from NASA and NOAA to initially forecast that the same would happen during SC25, which they later admitted was a mistake.

The new research hints that SC24's lull was caused by the CGC minimum, likely making it the quietest sunspot cycle for around a century. If this is the case, then the unexpected activity of the current solar maximum means the sun is returning to "business as usual," McIntosh said.

Previous research had already suggested that the CGC may have played a role in the recent sunspot cycle confusion, including a 2023 study from members of Adam's research group and a 2024 paper that analyzed sunspot patterns with machine learning. However, the most recent findings are the first to suggest that the CGC minimum may be over.

The new study also suggests that the CGC may have a greater influence on the sunspot cycle than researchers previously realized, Adams said. As a result, solar cycle forecasters should "definitely" keep a closer eye on this phenomenon when predicting upcoming cycles, he added.

More to come?

If the CGC is turning over, then upcoming sunspot cycles will likely be as active as the current cycle and could eventually get stronger as we approach the CGC maximum, the researchers wrote.

"We just passed the CGC minimum, and it will be another 40 to 50 years before the CGC maximum," Adams told Live Science. "As a result, the next CGC maximum will likely occur around Solar Cycle 28."

Using "back-of-the-envelope calculations," we can assume that when this happens, solar activity could be around twice as high as it has been during the current maximum, Adams added. However, it is hard to tell for sure, because the CGC's effect on solar activity "can be a little inconsistent," he admitted.

Related: 15 dazzling images of the sun

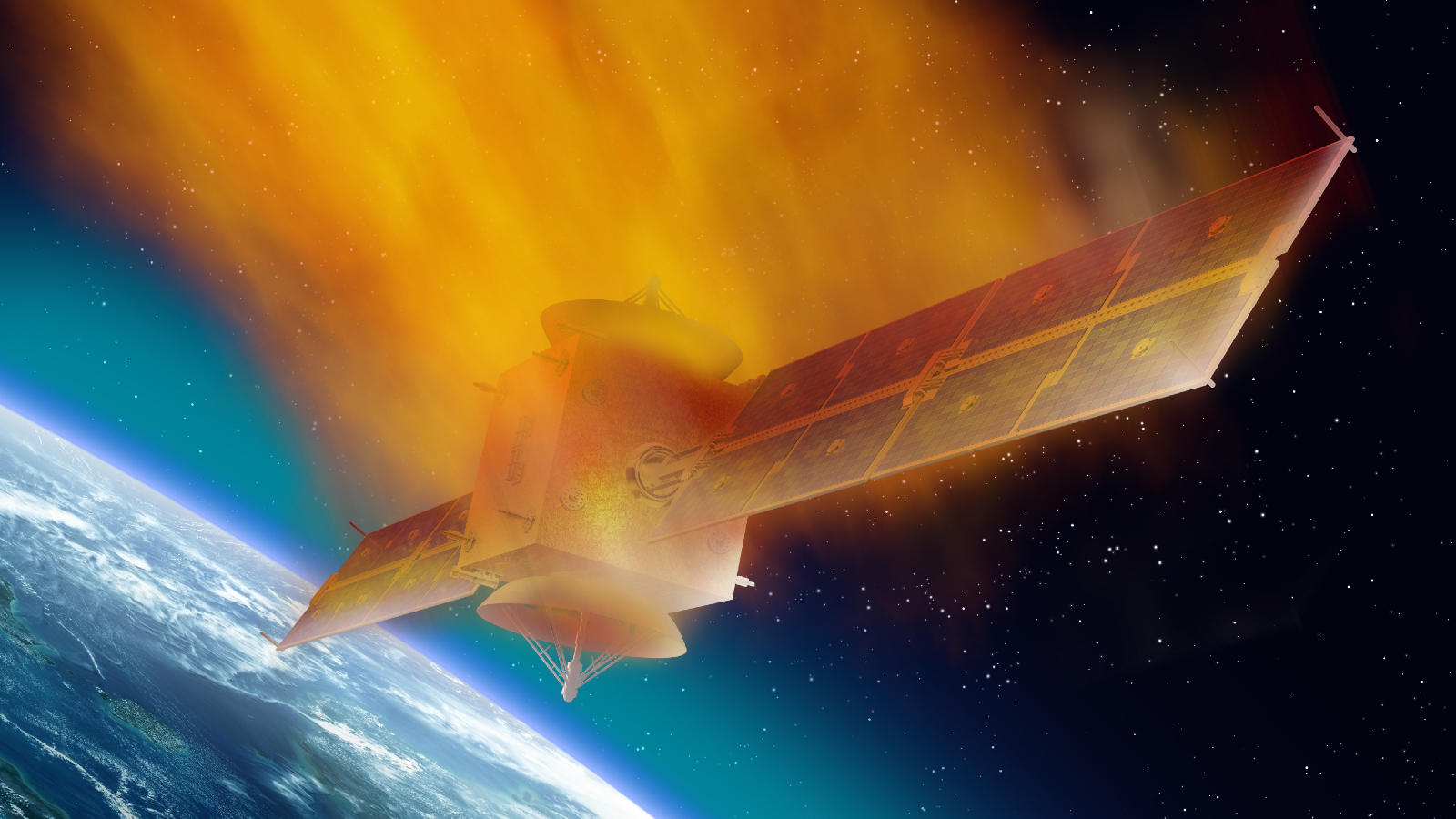

If future solar maxima are more active than the ongoing peak, it could spell trouble for satellites, which can be knocked out of orbit as Earth's upper atmosphere swells. Several spacecraft have already fallen foul of this in the past few years. However, the problem could get worse in the coming decades due to the rapid expansion of private satellite "megaconstellations" that may be ill-equipped to deal with radiation spikes.

"Most [private] satellites usually take into account a model of the space climate when they are being made," Adams said. But they "are not considering the long-term variations that we are seeing."

Increased solar activity could also be a problem for astronauts, who are vulnerable to harmful radiation shooting out of our home star, Adams added. And there will likely be lots more people in space in the coming decades due to upcoming missions to the moon and Mars, as well as an increase in private spaceflight.

An uncertain future

But not everyone completely agrees with the new findings.

McIntosh, who was one of the first researchers to correctly forecast SC25 when he previously worked at the National Center for Atmospheric Research at CU Boulder, told Live Science that it is "too early" to make any firm conclusions about the CGC.

The main issue is that proton flux has only gone down over the past year, so it could just be a temporary dip caused by the natural variability of the sun, McIntosh said. As a result, the study team probably needs a couple more years of data for their results "to be definitive," he added.

There's also no baseline data for comparing CGC cycles, since satellites have only been able to accurately track proton flux over the past 30 to 40 years.

McIntosh also warned that the new study could be overestimating the effects of the CGC on the sunspot cycle, because we still don't know how the two cycles interact. At present, researchers are also struggling to agree on what the CGC is and how we define it, he added.

However, while McIntosh does not entirely agree with the new study, he did say it is "intriguing" and "well intentioned," and that the findings could help forecast the next sunspot cycle. While the CGC remains mysterious, it is likely "an intrinsic part of the [sunspot cycle] puzzle," he added.