Two days before India celebrated its 76th Independence Day, a nine-year-old Dalit boy from Rajasthan’s Jalore district died at a hospital in Ahmedabad after allegedly being thrashed by his school principal.

The boy, Inder Meghwal, according to initial reports, was punished by Chail Singh, a Rajput, for quenching his thirst from a water pot reserved for the upper caste teacher.

The incident triggered a massive outrage, leading to the immediate arrest of the accused schoolteacher and drawing the national gaze upon Saraswati Vidya Mandir, a private school in Jalore’s Surana village, and the contentious earthen pot. Though the pitcher is nowhere to be found on the school premises, it has stirred the caste pot in Rajasthan.

Surana, a small village in Sayala tehsil, boasts visible signs of development — government and private schools, hospitals, electricity and metalled roads. The village, which has a sizeable population of Rajputs and Dalits, has managed to do away with ill practices such as child marriage and open defecation but caste discrimination is a different story.

While members of the upper castes here claim Chail Singh’s school never had a separate water pot for the principal, the Dalits too rule out any link between Inder’s death and caste bias.

“Chail Singh had hit the boy [Inder]. He accepted this fact and even gave ₹1.5 lakh for his treatment. The caste angle being added to the case is baseless. This school was the most affordable institution in the village where students used to get good education. Now the future of all these children is at stake,” says Devashi Walaram, the deputy sarpanch of Surana, who belongs to the Other Backward Classes (OBC).

The village has a woman sarpanch, Jaswant Kanwar, a Rajput, who is hardly visible in the ongoing controversy as she is nursing her ailing husband.

The denial of caste discrimination by the villagers has forced Inder’s father, Devaram Meghwal, to move out of their house in Surana. He along with his wife Pawani Devi and three sons are currently staying at his brother Parvat Kumar’s house on the village outskirts where the family has found support from activists, politicians and relatives.

Atrocities against SCs/STs

Rajasthan — the largest State in terms of geographical area of 342,239 sq. km — has a population of around 8 crore, including 89% Hindus and 9% Muslims. Among the Hindus, the Scheduled Castes constitute 18% of the population, followed by the Scheduled Tribes at 13%, the Rajputs at 9%, and the Brahmins at 7%.

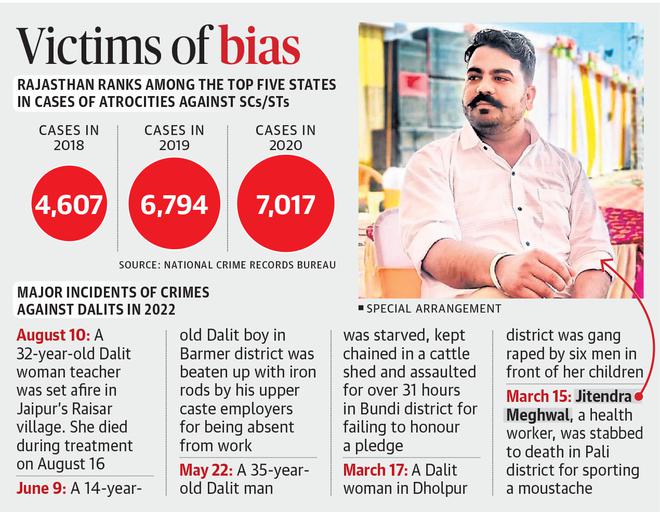

Despite this massive presence of SC/ST population, Rajasthan ranks fourth — after Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh — in the country in cases of atrocities against the community. As per data of the National Crime Records Bureau, the State recorded over 7,000 cases of crimes and atrocities against SC/ST community members in 2020.

The NCRB figures are just the tip of the iceberg, says Gopal, a distant relative of Mr. Devaram who is actively involved in getting justice for Inder. Mr. Gopal is also associated with a Dalit rights organisation, Bhim Sena.

“We cannot get a haircut in this village as the barbers, who belong to OBCs, refuse to touch our head. We have to go to other villages and sometimes to Sayala [the tehsil head office 25 km from Surana] to get a haircut. If this is not discrimination, what else is?” asks Mr. Gopal. The Bhim Sena, he says, is spearheading a fight for the right of Dalit grooms to ride a horse to their wedding — a usual practice for the rest.

In 2019, a groom from the Meghwal community in Bikaner was beaten up by upper caste men for riding a horse on his wedding day. The attackers even vandalised a vehicle in the groom’s convoy, forcing the family to seek police help.

Not just horses, even a sherwani can invite death threats, says Kantilal Meghwal, another Dalit man who had to seek police protection to be able to wear the outfit for his wedding.

“I got death threats from the Rajputs who could not accept the fact that a Dalit could wear such expensive clothes. Because I was aware of the law and my rights, I contacted the police. Not everyone can dare to do that,” says Mr. Kantilal, who works as a teacher at a government school.

Dalits in Rajasthan have been killed for even sporting a moustache, recalls Tolaram Meghwal, another member of the SC/ST community. Jitendra Meghwal, a COVID health assistant, was stabbed to death by two upper caste men in Pali district in March this year allegedly for wearing a moustache. While the police immediately arrested the accused, they denied any caste angle to the attack, calling it a case of old enmity.

‘Tradition, not discrimination’

The homes in Surana village can easily be identified on the basis of caste. No one needs the names. To get directions one has to ask, “Meghwalo/Harijan ko ghar kidhar? (Where are the houses of Meghwals, Harijans?)” and “Thakuro Kathe? (Where do Thakurs live?)”.

“But what is wrong in this system? Yehi pratha hai (this is tradition). It doesn’t mean that Dalits are being dominated here,” says Bhoor Singh, owner of Shree Dadaji Gau Seva Samiti, the biggest cow shelter in Surana. Mr. Singh claims that Dalits enjoy “equal rights and respect” in the village.

“I have Dalit friends and I invite them to family functions,” says Nayan Singh, another Rajput, while rubbishing the claims of caste discrimination.

The village has four big temples and all of them are open to members of SC/ST communities, says Manglainathji Maharaj, a priest at Dudheshwar Mahadev Mandir, the oldest temple in Surana. But there is a rider.

Parbita Harijan, 78, who lives near the Mahadev temple, says he visits the premises but doesn’t touch the idol. “This I do of my own will. I am not supposed to touch anything that is pious.” Asked why he should not touch the idols, he says that is what he has learnt from his elders.

“There is no discrimination. It is our custom. We are taught to do all this,” says Pakka, a Meghwal, who lives next to the house of Inder’s uncle on the village outskirts.

Raju, another man from SC/ST community, lives next to a big plot that was being used by the Rajputs to protest against the police action on Chail Singh. Hundreds of upper castes members gathered here on August 16 to submit a memorandum to Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Committee chief Govind Singh Dotasra, stating that all allegations of discrimination against the accused teacher were false and the boy’s family was playing politics over his death to extract money from the government.

Mr. Dotasra has announced ₹20 lakh compensation from the Congress party funds to Inder’s kin and assured them of a fair investigation into the matter.

Mr. Raju and his family watched the protest from their house but stayed away from the controversy.

“Politics is for the upper caste, not for us,” says Mr. Raju, who works as a carpenter but is still called to remove carcasses of animals that die in the house of Rajput families. His mother is asked to clean the clutter left behind after wedding celebrations in upper caste households.

“I don’t find anything wrong in this. We ask them whatever money we want to clean the mess,” says Mr. Raju.

But are they invited to the weddings? “Yes, we attend their functions. We eat their food as well. But we can’t eat at their house. We have to bring food back to our home and eat,” he says.

Separate cremation grounds

In Surana, with a population of around 8,000, discrimination persists even in death as each community has a separate cremation ground.

“How can you call this discrimination? The same is being practised across western Rajasthan,” says Ran Singh, a Rajput.

Caste discrimination has become extraordinarily normal in Rajasthan as it is taught to everyone since birth, says Rajiv Gupta, a retired professor from the Department of Sociology, Rajasthan University. “Rajasthan is a feudal State and there is no doubt about it. The panchayats here, mostly governed by Thakurs and Rajputs, work as kangaroo courts as the upper castes have control over economic resources,” says Prof. Gupta.

He, however, adds that a feudal mindset and deep-rooted caste bias are not specific to Rajasthan and prevail across India, a prominent example being the Dalit gang-rape case in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh, which evoked global condemnation.

Prof. Gupta says earlier the lower castes were not aware of the egalitarian model and hence everything was going fine, but now even the SCs/STs have become vigilant about their rights and that has led to a spurt in crimes against the community. “The worst part is being played by the government. Rather than working on eradicating the caste system, it has introduced a compensation system to pacify the victims. This will not work in the long term,” says Prof. Gupta.

Dalit rights activist Martin Macwan, who runs an NGO called Navsarjan, says atrocities against Dalits are rampant across India and the reason behind it is lack of political will.

“The kind of work done to eradicate untouchability in pre-Independence days is completely absent post-Independence. Unless you have a concrete will that is manifested through a concrete programme and allocated resources, there cannot be any improvement,” says Mr. Macwan.

School open to all

Saraswati Vidya Mandir, where Inder was allegedly thrashed on July 20, has been running in Surana since 2004. Chail Singh, the founder of the school, was paying ₹10,000 as rent for the school that has seven big and small rooms, two verandas and a playground.

Affiliated to the Board of Secondary Education, Rajasthan, the school caters to students from Classes I to VIII. It has about 350 students and eight teachers, five of whom are from the SC/ST community. Three of the five teachers are Meghwals, the caste that Inder belonged to. “We have 73 students from the SC/ST community, 126 from the general category and 156 from OBCs,” says Ashok Kumar Jeengar, a teacher who has taken charge of the school after Chail Singh’s arrest.

Inder, a Class III student, used to sit with 40 others on the porch of the school building, says one of his classmates who was a witness to the July 20 incident. He says he is tired of repeating the same statement in front of policemen, journalists and administrative officials that Inder was not slapped because he drank water from the principal’s pot but because he got into a fight with another classmate over a book.

“Maasaab [Chail Singh] had hit both the students,” says the boy, stressing that there is no separate pot in the school and everyone drinks water from a cement tank installed on the premises.

Fight for survival

At his brother’s house on the outskirts of Surana, Mr. Devaram is finding it difficult to accommodate the guests visiting the family to extend their support. A huge open space next to the fields is being used for seating arrangements but there’s no provision for protection from the rain. A tent brought on rent, too, has failed to serve the purpose.

“They [Rajputs] say I am playing politics. I want to ask them how a father can play politics over his son’s death,” says Mr. Devaram, showing the injuries he sustained during a police lathi charge inside his house when he was protesting with Inder’s body.

“I have lost everything that I had. I am fighting for the survival of my family now,” says Mr. Devaram who used to run a cycle repair shop on the pavement outside the house of a Rajput family.

Mr. Devaram is not denying that he sought compensation from the government. “I asked for the money as now I will not be allowed to work in the village. My entire family will be ostracised. No one will buy anything from us and we won't be given any help as well. How am I supposed to survive? My brothers have supported me and I owe financial help to them too. The money is needed,” he says.

Inder’s mother Pawani Devi clearly recalls the day her son told his father about the thrashing at school “because of the water pot”. He complained of pain in his ear and Mr. Devaram got some medicines from a local pharmacy. As the pain increased, the family took him to a hospital in Bagoda village, 13 km away from Surana. The doctors gave him medication and the pain subsided for a while.

“He again complained of pain two days later. This time we took him to another private hospital in Bhinmal, a township near Surana after Sayala. The medicines again helped alleviate the pain and we brought him back home,” says Ms. Devi.

As the pain persisted, the family says it visited eight hospitals and travelled over 1,200 km between Rajasthan and Gujarat, where on August 13 Inder breathed his last at a government hospital.

Around 40 km from Surana, Chail Singh’s home in Amba Ki Goliyan Jhaab wears a deserted look. His wife Sukhi Singh is still in a state of shock. Having little idea aboutwhat has happened to her husband, she says her two sons — Gopal and Lakshman — were also studying in Saraswati Vidya Mandir and use to live on the school premises with their father. They use to travel home every weekend.

Chail Singh was arrested on August 14 on a complaint lodged by a brother of Mr. Devaram. He was booked for murder and under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

“We have a piece of agricultural land where a Dalit help works. Our house is still like an old village home with mud walls. We couldn’t think of anything beyond earning two meals a day and saving some money for the treatment of my ailing in-laws. Don’t know how this caste angle surfaced,” says Ms. Sukhi.

Political support

Roopa Ram Dhandev, Congress MLA from Jaisalmer, says “no inquiry is needed in Inder’s death case as caste discrimination is a truth in Rajasthan”.

“You are visiting the State in very good times. In my childhood days I had seen Dalits being asked to tie a broom on their back as they were considered ‘apavitra (untouchable)’. When they would walk, the broom was supposed to clear their footmarks. Dalits were not allowed to spit, hence they would tie a pot around their neck and spit in it,” says Mr. Dhandev.

The ruling Congress, which has extended full support to the grieving Dalit family — its MLAs, including senior party leader Sachin Pilot, visiting Surana soon after the incident — has questioned the absence of the Opposition BJP from the scene.

BJP MLA from Jalore Jogeshwar Garg, who hasn’t visited the Dalit family till now, released a video earlier this week expressing his doubts about the caste angle in Inder’s death.

“I have spoken to the villagers. They all say that there was no water pot in the school. There is no doubt that the boy was beaten up by the teacher and he died. The accused has been arrested and an investigation is being conducted. Whether he was beaten up for being a Meghwal and touching the water pot will be cleared in the probe,” he says.

Political experts say the BJP does not want to hurt the Rajputs by supporting the Dalits.

Angry Rajputs

The Rajputs in Surana are angry as they feel no one is ready to hear their version. “That boy had an acute infection in the ear. No one can die after getting just one slap. The teacher’s family is also a victim but all the limelight is being hogged by the Dalit family. We have sympathy with them but what they are doing is wrong,” says Aam Singh Parihar, a Rajput activist.

Mr. Parihar had planned to hold a massive protest and submit a memorandum to Mr. Pilot, who had criticised his own government while meeting Inder’s family.

Later the protest was cancelled as the police dispersed the crowd. “The Rajputs did not want to make Ashok Gehlot unhappy. They decided to give the memorandum to the PCC chief [Dotasra],” says Mr. Parihar.

Ratan Singh Prajapati, a taxi driver from Jodhpur who took a media team to Surana to cover the visit of Mr. Pilot, has another theory on why the Rajputs are angry. “They [Rajputs] are not upset about the village getting defamed. They are angry with the fact that now the Dalit family will become rich with the compensation given by the government and this will disturb the caste hierarchy in the village,” says Mr. Prajapati.