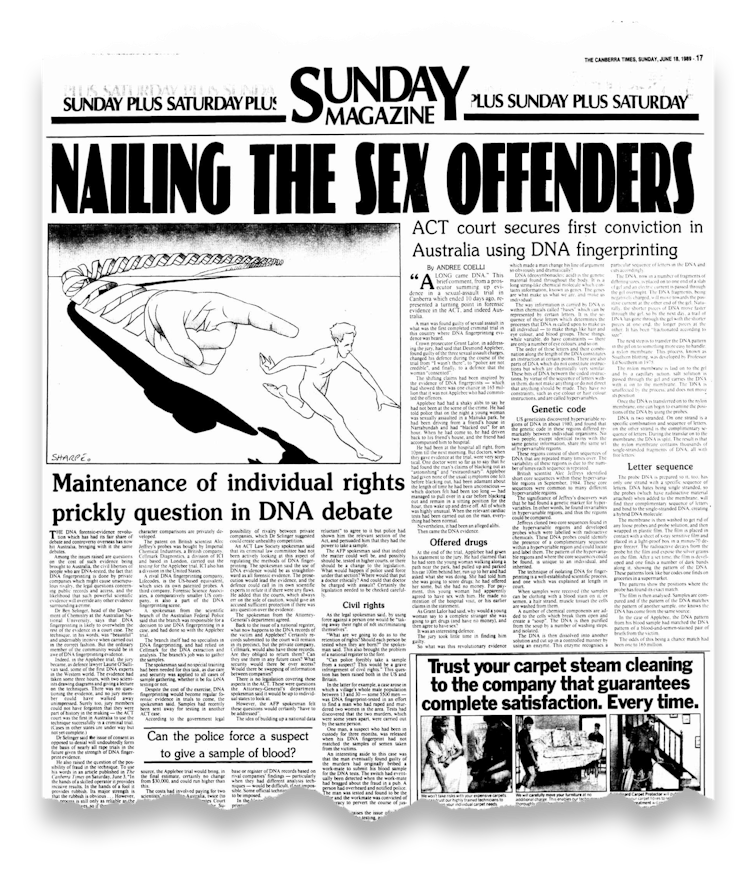

This month marks 35 years of DNA evidence being used in Australian legal cases. But unlike DNA firsts in other countries, Autralia’s is perhaps the most significant legal milestone that is practically unheard of.

The 1989 trial in the Australian Capital Territory Supreme Court of Desmond Applebee was a messy case, about a nasty crime. This case was the first time in Australia DNA evidence was admitted in court.

Importantly, it failed to properly engage with the legal and scientific issues DNA evidence raised.

The case graphically illustrates the challenge of interrogating novel scientific evidence – a difficulty that persists in Australia’s legal system today.

The Applebee case

In 1988, a knife-wielding serial rapist had sexually assaulted a number of young women in Canberra, including the 18-year-old daughter of a diplomat. Police suspected known offender Desmond Applebee because he fit the physical description, had used weapons in past crimes and had recently got out of prison – which the rapist had told one victim.

Police found a balaclava and guns in Applebee’s car. But Applebee claimed that at the time of the rape, he was unconscious from a fainting attack. The emergency room doctor who saw him shortly after, however, didn’t find symptoms of a fainting episode.

The diplomat’s daughter’s identification of Applebee from a photo line-up, after not picking him in an identification parade, was a potential weak point.

An identification parade is where the police place a suspect of a crime in a lineup of similar-looking people before the victim. If the victim identifies the suspect from the parade, it is considered stronger evidence than a photo line-up because the suspect is there in person and can object if they feel it is being done unfairly.

The Australian Federal Police turned to DNA evidence to firm up their case.

A DNA match

Forensic DNA testing was very new at the time. The concept had been proposed in 1985 by genetics researchers at the University of Leicester, led by Alec Jeffreys. It was used in a United Kingdom immigration dispute in 1985. It was then famously used as part of the investigation into the Leicestershire rape-murders of Dawn Ashworth and Lynda Mann, and ultimately led to the conviction of Colin Pitchfork in 1988 in the UK.

Forensic DNA testing was not done in Australia at the time. But Australian Federal Police officers had heard about the Pitchfork case. They had samples from the Applebee investigation hand-couriered to Cellmark Diagnostics in the UK, the company licensed by Jeffreys to use his DNA technique.

The tests showed a match between Applebee’s DNA and that of the rapist the police were looking for.

Over-egged claims

The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions flew Cellmark’s lab technician and supervisor to Canberra to testify in Applebee’s trial. Their testimony slightly over-egged the claims for their DNA testing.

For example, Cellmark’s lab technician drew a connection between the DNA test and genes, “which make us what we are […] all individuals”. However, the tests actually used characteristic repeated sequences in the non-coding or “junk” part of the genome, not genes. These sequences are where a pattern of DNA base pairs are repeated over and over again. The number of repeats varies between individuals. Jeffreys’ DNA test looks at the number of repeats.

Cellmark’s lab technician and supervisor also described the company’s test as producing a “DNA fingerprint”, metaphorically linking it to unique fingerprints.

However, the company’s DNA analysis involved several separate tests, each looking at non-unique characteristics, which were then combined. Only in combination did the tests support the “1 in 165 million” claim, whereas a fingerprint is a single, unique thing. This nuance was not made clear at trial.

The “1 in 165 million” claim was also calculated based on the frequency of the component characteristics in white people. Applebee, however, was Aboriginal. The data on how common his DNA combination was in white people wasn’t relevant to Applebee, and there wasn’t data available at the time to say how common his DNA combination was in other ethnicities. This, however, wasn’t raised during the trial.

After the DNA evidence was presented, Applebee changed his story. He hadn’t fainted, he said, but the sex was consensual. The jury took just half an hour to return a guilty verdict. Applebee was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Doubts over scientific evidence?

A weight of other evidence also supported the guilty verdict against Applebee. But the handling of the DNA evidence in the case was problematic.

Defendants have a right to interrogate the evidence against them.

But novel scientific evidence – that is, evidence based on newly developed science – underscores the difference in resources between the state prosecution and the individual defendant. Very few people have resources comparable to what the state has. Legal aid doesn’t entirely level the playing field.

The failure to highlight some of the problems with the DNA evidence in Applebee’s case was arguably partly his own fault. He had fired his lawyer and got another one only after the DNA testimony.

But unless the defence makes an argument, our adversarial legal system has no other routinised gatekeeping mechanism for dealing with novel scientific evidence.

Testing reliability

One interesting idea for putting novel scientific evidence through a rigorous examination process was floated in the United States in the 1970s. It was known as a “science court” and would provide a specialised assessment process for new scientific evidence.

More commonly, many jurisdictions including in the UK and US, incorporate a “reliability test” to assess scientific evidence in court.

This requires the prosecution to convince the court that its scientific evidence is sufficiently well developed and validated to be accepted by professionals in the field. Meeting the test implies there are independent experts available to the defence to critically examine the evidence.

Australian criminal law, however, does not have a reliability test. And that’s a problem because novel forms of scientific evidence will continue to be developed. Proteomics, DNA phenotyping, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence – such developments in science and technology will keep presenting the courts with new types of very complex, technical evidence.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Laura Dawes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.