The 10-story Brown Building, site of one of the deadliest workplace disasters in United States history, stands one block east of Washington Square Park in New York City. Despite three bronze plaques noting its significance, it has long been easy to pass by without further thought.

On March 25, 1911, however, thousands of New Yorkers gathered outside what was then known as the Asch Building, home of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Drawn by a brief but raging inferno, they bore horrified witness to dozens of factory workers with no way to escape gathering on the ninth-floor window sills, desperately jumping, and smashing onto the sidewalks far below.

Horse-drawn fire crews responded within minutes to reports of the fire, which broke out on a Saturday afternoon at closing time, and it took only a half-hour to douse the flames. But the fire had had its way.

One hundred and forty-six people lost their lives. Most of those who died worked on the ninth floor, where safety measures consisted of little more than pails of water, despite the potential fire bomb around them: overflowing bins of discarded cloth and lint, combined with tissue-paper patterns hung across the ceiling. Locked doors, an inadequate fire escape and other fire code violations meant many workers could find no way out except the windows.

Firemen were left to stack the lifeless bodies on the sidewalk. The vast majority were girls or young women: meagerly paid laborers, and most of them Jewish or Italian immigrants.

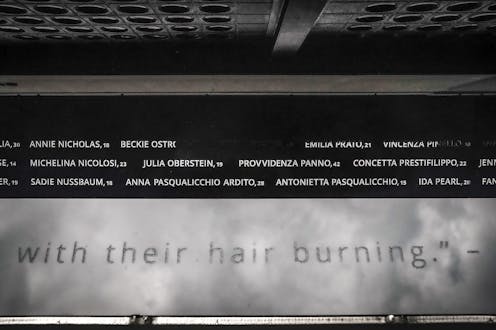

On Oct. 11, 2023, the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition dedicated a striking memorial at the site of this tragedy. The initial installation features a stainless steel ribbon extending in two parallel strands along the ground floor, displaying victims’ names and survivors’ testimony, written in their native languages: English, Yiddish and Italian. Over the next few months, another gently twisting ribbon traveling from the window sill of the ninth floor to the ground level and back up again will be added.

The memorial offers a bold and graceful reminder not only of the fire but of its imprint on the world we inhabit today.

When I asked the students in my history class at the University of Michigan if they had heard of the Triangle fire, I was shocked to see almost all raise their hands. Many were familiar with how the disaster inspired the growth of labor activism and worker protections. Few of them, however, had thought about the central role of American Jewish women, the focus of my research.

Tense 2 years

Only two years before the fire, a walkout over working conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory had sparked a series of labor actions that culminated in the Uprising of the 20,000, the largest American women’s strike ever.

That disciplined activism was led by a small cadre of young Jewish immigrant working-class women. Years earlier, they had essentially created a branch of their own – Local 25 – within the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Their example led to a surge of strikes nationwide and forced the labor movement to finally take the needs of unskilled workers and women workers seriously.

The Triangle bosses and other owners hired thugs to assault strike leaders and picketers. The police likewise felt free to beat the picketers, which only abated when upper-class partners in the Women’s Trade Union League joined the picket lines – raising fear among the police that they might be striking society matrons.

The Triangle Factory was among the 339 shops that “settled” with the union in February 1910, with concessions that included higher wages, a 52-hour week, four paid holidays per year and a promise to no longer discriminate against union members.

The strikers’ call for better safety standards, however, had been ignored by the male union representatives and owners who had worked out the settlement.

Moral force

Local 25 grew from a few hundred to 10,000 members over the course of the 1909-10 strike. That organizing prowess would be seen again in the wave of protest and indignation that followed the 1911 fire.

The unions’ strength could be seen in the funeral march that accompanied the fire’s seven unidentified victims to a municipal burying ground, as a crowd of 400,000 assembled to march or watch the procession.

The power of the activists’ moral indignation emerged in full force at a memorial meeting held a few days later. Workers grew restive as wealthy philanthropists, city officials and liberal reformers promised investigatory commissions – which they feared would mean little real change.

Rose Schneiderman, one of the working-class immigrant labor activists who had helped organize the 1909 strike, was also on the platform. Reformer Frances Perkins, who would soon become a close ally, noted Schneiderman trembling over the loss of comrades, friends and co-workers.

Schneiderman took the podium, excoriating the industry’s brutality and focusing on the unrealized power of the workers themselves. “I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies,” she declared, “if I were to come here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public – and we have found you wanting.”

“I know from experience it is up to the working class to save themselves,” Schneiderman told the audience.

Birth of the New Deal

Yet the working class ended up needing allies like Perkins, who was instrumental in establishing a citizens’ Committee on Safety, and then a legislative Factory Investigating Commission as well.

On the day of the fire, Perkins had been enjoying tea at a friend’s house on Washington Square and rushed toward the commotion across the park, arriving on the scene to see bodies falling from the sky. That scene and Schneiderman’s speech left an indelible impression on her – as they did on many New Yorkers.

For several reasons, including public outcry about the fire, this was the moment when New York City’s political machine began to shift its focus and address workers’ needs. Schneiderman and other activists worked with Perkins on investigations that led to the overhaul of New York’s safety and labor laws, such as a 54-hour maximum work week.

The young women whose pain had galvanized public response continued their union work, traveling around the country to help organize many of the strikes their activism inspired. Some also made an impact at the governmental level. Schneiderman became a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and influenced her views on workers’ needs, as well as those of her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Perkins became President Roosevelt’s secretary of labor in 1933 and was the first woman to serve in a U.S. cabinet position. She brought the New York reforms born in the wake of the fire into the New Deal, the slew of social programs the Roosevelt administration introduced to help Americans struggling through the Great Depression.

Schneiderman, too, had a role: the only woman to serve on the New Deal’s Labor Advisory Board. As Perkins later recalled, the day of the Triangle fire was “the day the New Deal was born.”

For 112 years, the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory have called out silently from the sidewalks and window frames of the Brown Building, which is now part of New York University’s campus. The new memorial calls on the passersby to stop, note and honor that one horrific half-hour, etched indelibly into the story of the city and the nation.

Karla Goldman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.