As a young politician he was known and feared for his denunciations of real or falsely accused “subversives” and for the vicious campaigns he fought and won against Jerry Voorhis for a seat in congress and against Helen Gahagan Douglas for the senate.

As President Dwight Eisenhower’s vice-president from 1953 to 1961, he acquired a knowledge of international politics and a reputation for forthright dealings with Soviet and other antagonists of the US; at home, his relentless pursuit of political advantage fastened firmly on him two cruel labels: the name Helen Douglas had given him, Tricky Dick; and the question the Democrats asked in 1960: “Would you buy a used car from this man?”

In 1960 he was the Republican presidential candidate and was beaten for the presidency by John Fitzgerald Kennedy by a tiny margin of votes.

There were many who thought the decisive margin had been dishonestly won, but Nixon refused to question the result. Instead he ran for governor of California in 1962 and lost. After a graceless outburst against the press, it looked as if his career was over. But he threw himself into working for Republican candidates, including Barry Goldwater, the party’s defeated 1964 presidential nominee, and won the Republican nomination himself in 1968.

Nixon emerged a narrow winner in that year’s tempestuous election and embarked, with his national security assistant, Henry Kissinger, on a tortuous diplomatic strategy intended to extricate the United States from the Vietnam War without incurring the unpopularity he believed would result from an abrupt or unilateral withdrawal. As a consequence, the contrast between his proclaimed peace-keeping intentions and the continued bombing of North Vietnam and Cambodia heated opposition to the war to even higher temperatures than under his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, and it was Nixon and his aides’ fear of the peace movement, as well as their determination to win by a wide margin in 1972, that tempted them to indulge in the dirty tricks, illegal actions and excessive use of presidential power that led to Nixon’s downfall.

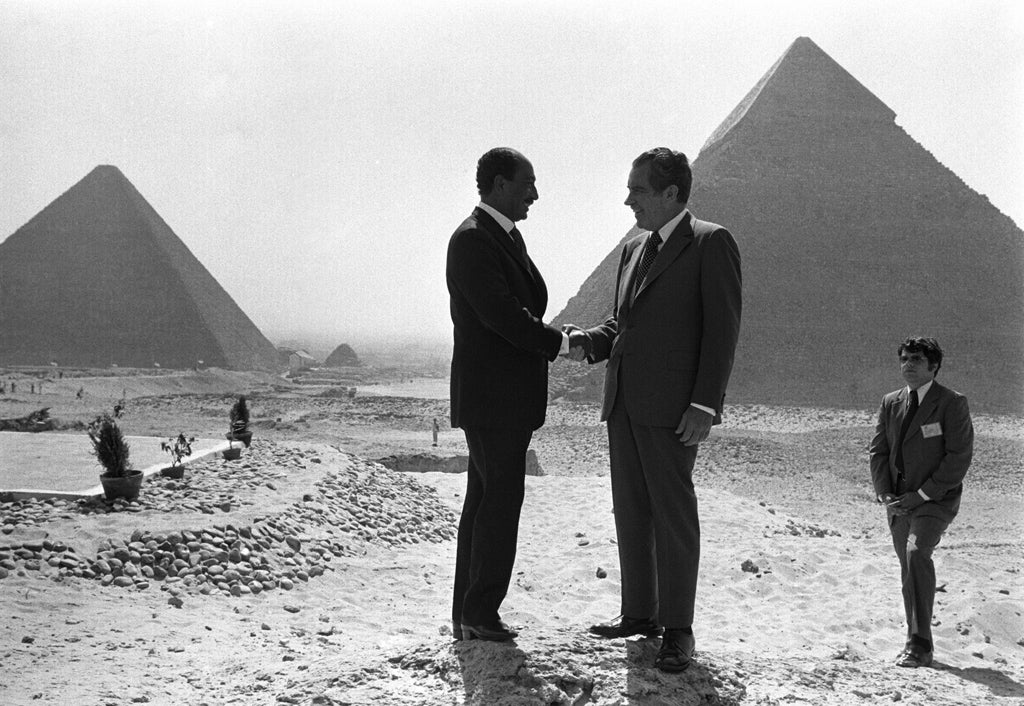

Nixon and Kissinger had notable success in their negotiations with the Soviet Union, and Nixon made history with his visit to Peking in 1972, as well as depriving the Democrats, whom Nixon had always accused of being soft on communism and of “losing” China, of some of their best arguments.

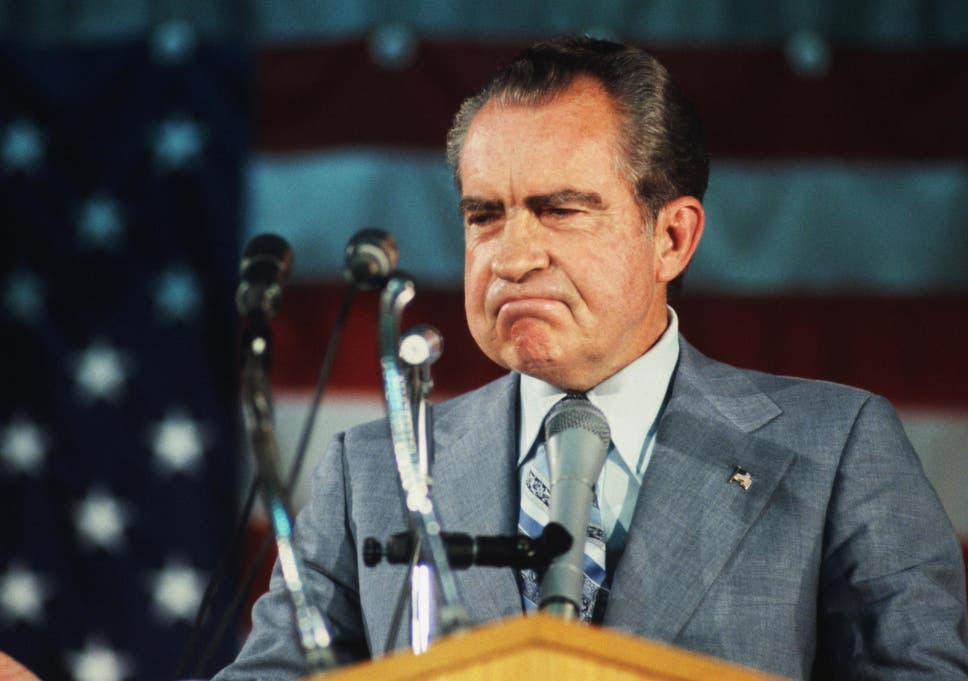

Nixon’s personality was baffling. He was an international statesman with a wide outlook and an incomparable knowledge of the world of the Cold War period; he was also a fierce political infighter with a peculiar habit of innuendo which, even more than his ruthless use of the issue of domestic communism, made him uniquely detested by his liberal and Democratic opponents. Few politicians have generated a cottage industry in psychological theorising and psycho-biography in the way that he did; yet although he often seemed to be on the edge of psychological crisis, his inner strength carried him through pressures that would have destroyed weaker personalities.

His unscrupulous behaviour in office culminated in the Watergate affair. A break-in carried out by Nixon’s political henchmen at the Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate building, in Washington, set off a chain of events which led through press investigation, congressional hearings and court action to the denouement in the summer of 1974. Nixon was found by a grand jury to be an “unindicted co-conspirator”. The Supreme Court ordered him to release secret White House tape recordings which would prove that he had lied when he proclaimed his ignorance of Watergate and other malfeasance. He was left with no alternative but to resign or be impeached and convicted by the Senate of “high crimes and misdemeanours”.

Yet in many respects Nixon had been a restrained as well as an able president. After his disgrace, he worked for his own rehabilitation with courage and pertinacity, publishing numerous books in his quest for recognition as an elder statesman: a quest which could be said to have met with success when President George Bush invited him to make a major speech at the 1992 Republican convention.

Richard Milhous Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, a small farming community near Los Angeles, in 1913. He was descended on both sides of his family from Irish Protestant stock settled in the United States since the early 18th century. His mother, Hannah, a lasting influence, and a woman of great strength, was a Quaker. His father, Frank Nixon, worked at a number of jobs, including driving a streetcar, before acquiring a lemon grove which failed. He then operated a small grocery in Whittier, southeast of Los Angeles, where Richard went to high school and to Whittier College, a Quaker institution. Richard did well at college, and went to Duke University Law School in 1934.

In 1937 Nixon went to work for a law firm back home in Whittier, and in 1940 he married Thelma Ryan, always known as Pat. During the Second World War he served as an officer in the US Navy, some of the time in the South Pacific. He was a very successful poker player, and left the navy with several thousand dollars in winnings. In 1946 he defeated a Democratic incumbent, Jerry Voorhis, in a notably dirty campaign for a seat in congress and in Washington he became a member of the House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities, which was busy rooting out supposed communist and other, mostly left-wing, subversives.

Nixon recognised that the Hiss case played a crucial part in his career. It gave him, he admitted, “publicity on a scale that most congressmen only dream of achieving”. Alger Hiss was a graduate of Harvard Law School, a former law clerk to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, an aide to President Roosevelt. He represented an effortless superiority that brought out all Nixon’s class resentment and envy. Hiss was also, however, a deeply troubled man, a liar and, in spite of all his denials, a communist agent. Nixon was Hiss’s most hostile questioner at a hearing of the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1948; getting Hiss became a personal obsession. Hiss was convicted of perjury in January 1950. Nixon’s political career was well launched.

In 1950 Nixon ran for the Senate in California and defeated the actress Helen Douglas in what was to be remembered as an infamous campaign. Nixon called Douglas, a mainstream New Dealer, the “pink lady”, and made much play with “the pink list” of issues on which she was supposed to have voted the same way as the solitary communist in congress, Vito Marcantonio. It was on the back of these two victories, as the exposer of Hiss’s communist past and as the denouncer of Douglas’s (fictitious) communist sympathies, that Nixon arrived in the Senate. The Korean War was raging, and Dwight Eisenhower, in his election campaign in 1952, promised to end it. Elderly, a stranger to party politics, and associated with the war in Europe, not with the American West and its preoccupation with the Far East, Eisenhower chose Nixon, the aggressively anti-communist young congressman from California, to balance his presidential ticket.

Nixon’s career as a national politician almost ended before it had begun, however. He was accused of benefiting from an illegal slush fund secretly raised by a group of businessmen to pay his expenses. Eisenhower was furious, and Nixon was advised to stand down. Instead, he chose to fight, and to do so on television, just beginning to come into its own as a forum for political conflict. He did so in the notorious “Checkers” speech, so called because of his sentimental mention of the family dog of that name. In effect, he presented himself as a poor man being persecuted by those more privileged than himself. Liberals despised Nixon for the tasteless self-pity he had used to defend himself. But the leaders of his own party were impressed, and so were many ordinary Americans.

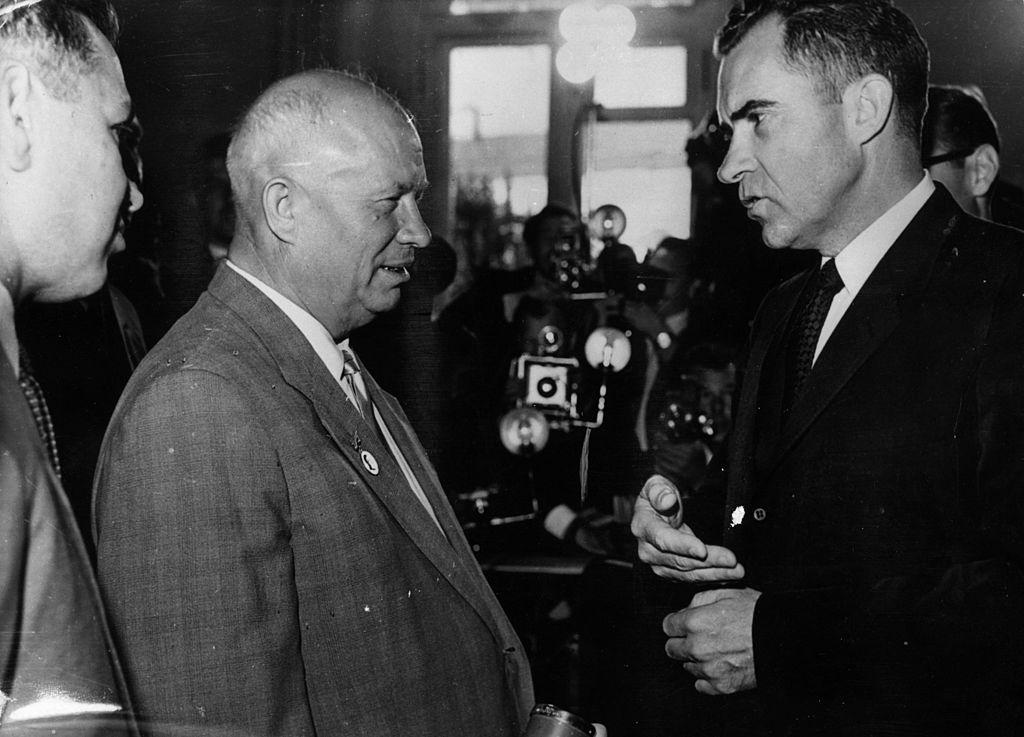

As vice president to an older president in poor health, Nixon travelled incessantly, laying the foundations for his extraordinary familiarity with politicians and other leaders around the world. His most notable encounter was with the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in the kitchen of the American exposition in Moscow in 1959. Khrushchev tackled Nixon aggressively, but Nixon seemed to have given more than as good as he got. He was the Republican presidential candidate in 1960, and expected to beat whatever candidate the Democrats put up.

That made the 1960 campaign all the more disappointing. Few had predicted either that Kennedy would be the candidate or that he would display such political magnetism. The televised debates were an especial disappointment. Nixon had reason to view television as a medium he had mastered; instead, he seemed saturnine, almost sinister, in comparison with Kennedy.

After his defeat, Nixon decided to run for Governor of California. When he was defeated there by the Democratic State Attorney General, Edmund G “Pat” Brown, something snapped. On 7 November 1962, at what he called, and his audience of reporters believed to be, his “last press conference”, Nixon raged at what he saw – not altogether unfairly – as bias on the part of the reporters against him. He sarcastically commiserated with them that “you won’t have Nixon to kick around any more”.

Nixon himself said at the time, “As a political force ... I am through.” It was not long, however, before he was planning his return. He decided that he should be in New York, both because he needed to earn money in large quantities, and to take maximum advantage of his field of greatest expertise, in foreign policy. At the same time he threw himself into speaking tours for Republican candidates, building up a portfolio of political credit on which he would be able to draw when he needed it. By the autumn of 1963, he was established as a name partner in the prominent Wall Street law firm now called Nixon, Mudge, Rose, Guthrie Alexander & Mitchell, and he and his family had moved into the same luxurious Park Avenue apartment building as Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York State.

The assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963 and the succession of Lyndon Johnson improved both Republican prospects and Nixon’s chances of winning the Republican nomination again. In 1968 Nixon easily beat off Rockefeller’s challenge, though at the 11th hour there was a surprisingly strong run by the governor of California, Ronald Reagan. The Democrats were bitterly divided, with first Senator Eugene McCarthy and then Senator Robert Kennedy campaigning for the anti-war vote. Hubert Humphrey, whom President Johnson had hoped to designate as his heir when he himself abdicated the presidency, was damaged by his association with Johnson, as his vice-president, and by an unpopular war. In the end, with Humphrey making a last-minute comeback, Nixon scraped into the White House almost as narrowly as he had been beaten eight years before.

Even before the election, Nixon as candidate had suggested that his administration would be neither a conventional Republican one, nor the ideologically pure right-wing one the conservatives yearned for. He persuaded two Harvard professors to take key posts on his staff: Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a maverick Democrat, and Henry Kissinger, Rockefeller’s adviser on foreign policy. Both started out boldly. For two years, Pat Moynihan sought to persuade an apparently not altogether reluctant Nixon to attack the problems of poverty and the urban underclass with a guaranteed family income plan.

He offered Nixon a vision of himself as an American Disraeli, a conservative man bringing in progressive measures. But by late 1970 it was clear that the plan was in trouble, beleaguered by a coalition of liberals and conservatives against the centre. Although Nixon called it “the most important social legislation in 35 years”, in 1971 it was finally killed off in congress. By August that year, the president himself gave welfare reform lower priority than the gathering problems of inflation and the weak dollar. In December 1971, in the Smithsonian agreement, under cover of a multilateral realignment of currencies, Nixon in effect devalued the dollar for the first time since 1934. Only 14 months later, in 1973, he was forced to devalue again.

These important domestic and economic issues in his first term in the White House necessarily took second place to Nixon’s preoccupation with foreign policy. The most urgent task was to end the Vietnam War. Nixon found himself in agreement with his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, and allowed Kissinger to take the reins, relegating the State Department to a subordinate role and isolating, to the point of humiliation, Nixon’s choice as secretary of state, his old friend William Rogers.

Nixon and Kissinger believed that the United States could not win the war in Southeast Asia, but that the American people would not forgive a president who told them so. They therefore devised a strategy for extricating the United States without acknowledging defeat. This intention was eventually, in February 1970, justified by what came to be called the “Nixon doctrine”: it acknowledged the limits of American power and warned that “America cannot – and will not ... undertake all the defence of the free nations of the world”.

First, the US must “Vietnamise” the war, leaving as much of the fighting as possible to the South Vietnamese, backed by American political and economic support and if necessary by strategic bombing, of targets inside and outside South Vietnam. This policy would be supported by a diplomatic campaign, based on the premiss that the North Vietnamese were supported by both China and the Soviet Union.

The diplomatic campaign was not very successful in its primary objectives, since Nixon exaggerated the influence Moscow and Peking could exert over Hanoi. It did, however, bear dramatic fruit. In a series of secret negotiations Kissinger was able to prepare the ground for Nixon to fly to Moscow in May 1972 and come to a number of agreements with the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev, including a treaty limiting anti-ballistic missile sites to two in each country’s territory, and an interim agreement limiting the deployment of strategic missiles for five years. Even more dramatic was Nixon’s journey to China in February 1972. (This was one of the very few political events of the 20th century to be commemorated in an opera, John Adams’s widely produced Nixon in China.)

These foreign policy achievements, portrayed at the time by the newspapers and television as triumphs, were enough to ensure Nixon’s re-election by a landslide, and he was duly elected over the unfortunate Democratic candidate, Senator George McGovern, with more than 60 per cent of the popular vote, and by 520 votes to 17 in the electoral college. But Nixon and his inner circle in the White House and at the Committee to Re-elect the President had not been certain of victory. Outside the White House gates in 1969-72 there was a country deeply divided about the Vietnam War and social issues, a largely hostile press and at times mass demonstrations amounting almost to siege. Inside, Nixon’s deep suspicion of the unpatriotic instincts of the liberal Left, his personal paranoia and the influence of Kissinger and others in his entourage, who preyed on his fears, created an extraordinary atmosphere.

The first sign that something was wrong for the general public came with the news that five burglars, some of them associated with the CIA and others, it turned out, employed by the White House, had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex in Foggy Bottom, Washington, on 17 June 1972. But that was only the tip of the iceberg. It transpired that Nixon and his aides had committed numerous illegal acts: bugging the phones of colleagues and journalists, breaking into a psychiatrist’s office in the hope of looking at an opponent’s records, and the like. Secondly, they had planned and in some cases carried out “dirty tricks” of various kinds in their zeal to win the election. And they acted in a high-handed and arguably unconstitutional manner in a number of other respects, from the secretive conduct of foreign policy to the impoundment of monies appropriated by congress on a far greater scale than had ever been seen in the past.

Details of a number of other secret actions, from apparent tax evasion to the devastating bombing of Cambodia, became known, and contributed to a widespread feeling that the administration had been behaving as if it were above the law. A fatal combination of insecurity and arrogance, in fact, had created a climate in the White House that was to lead to exposure, retribution and eventually to disaster. Not just the media, but almost every part of the legal and informal constitutional system, including courts right up to the Supreme Court and eventually the judiciary committee of the House of Representatives, duly did its appointed work.

The country watched fascinated as a Senate committee chaired by the avuncular Senator Sam Ervin, a judge from North Carolina, stripped away the secrecy in televised interrogation of White House staff. One crucial revelation was that Nixon secretly recorded conversations in the White House Oval office – as many of his predecessors had done. On 23 October 1973, in the event which came to be known as the “Saturday night massacre”, Nixon ordered first his attorney general, Elliott Richardson, and then his deputy to dismiss the special prosecutor who was investigating allegations of presidential misdeeds. Both refused. Although the solicitor general, Robert Bork, did dismiss Cox, the result was an outpouring of national rage.

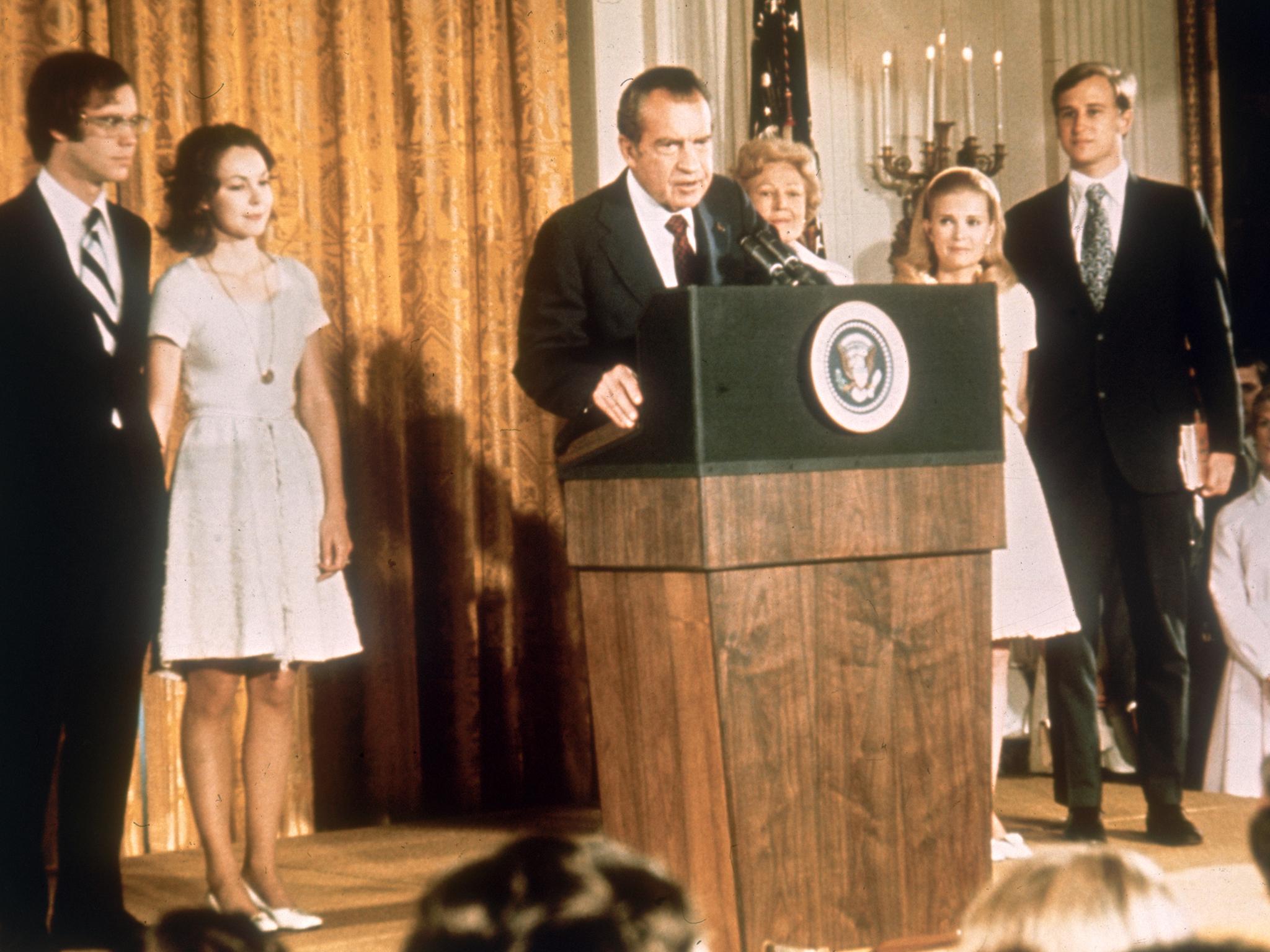

Throughout the spring of 1974 one associate after another was found guilty in court of illegal acts, and the House Judiciary Committee moved ominously closer to impeaching the president. In late July the Supreme Court rejected Nixon’s plea that the White House tapes should be kept secret, and by the beginning of August impeachment by the House of Representatives seemed inevitable; Nixon’s survival would be up to the Senate, sitting as a special court of impeachment. On 8 August Nixon announced that he would resign the next day. On 8 September his successor, President Gerald Ford, unconditionally pardoned Nixon for any federal crimes that he “committed or may have committed or taken part in”.

In his last night in the White House, just before his televised resignation, Nixon gave a highly emotional speech – also televised – to his cabinet, staff and family. It was sentimental, self-pitying, mawkish even, but it clearly announced Nixon’s intention to fight back. After saying that “they” would have called his father “a little man, a common man”, and calling his mother “a saint” – “Yes, she will have no books written about her. But she was a saint” – he ended by quoting what Theodore Roosevelt had written in his diary after the death of his young wife:

“You are really tested when you take some knocks, some disappointments, when sadness comes, because only if you have been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.”

The next day, in the worst moment of his humiliation, as the helicopter took him from the White House on his way to exile in California, some lines from an old Scots ballad kept coming into his head:

I am hurt but I am not slain,

I’ll lay me down and bleed awhile,

Then I’ll rise and fight again.

He was hurt, all right. There was blood too: he had to undergo a serious operation for a blood clot. Seven hours after the operation he almost died of a massive internal haemorrhage. He still faced unpleasant interrogations and possible legal action by various teams of prosecutors, and his financial position was disastrous, with a total of well over $1m in unpaid taxes, back mortgage payments and legal bills.

But he fought on, and did rise again. The first mile on the road back came with the television interviews he gave, for a fee of $540,000, to David Frost in 1976. In spite of some damaging admissions, more than 40 per cent of the viewers felt more sympathy with him after watching them – though almost 70 per cent also felt he lied in the interviews. There was more sympathy for him abroad than in the United States, and his most loyal friends were the Chinese communists. In 1976, on the fourth anniversary of his historic visit, he was given an almost presidential tour of China, ending with meetings with Mao Tse-tung and the new Chinese leader, Hua Guofeng. In 1978 he was well received in Britain, at the Oxford Union and at Westminster.

Nixon set himself to write a whole series of books, putting his own case on all the controversies in his life and asserting his credentials as an expert on international affairs. By 1980 he was advising the Reagan administration on foreign policy, and in the early 1980s he travelled widely, meeting world leaders and in 1984 even his old scourge, The New York Times, said: “He has emerged at 71 as an elder statesman, commentator on domestic and foreign affairs, adviser to world leaders, a multi-millionaire and a successful author and lecturer.” Even more striking, Katharine Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, which had played a key role in investigating the Watergate affair, stimulated a 1986 headline in Newsweek, her other publication, which announced: “Nixon’s Back”.

In 1990 he celebrated his golden wedding, published a new best-seller and attended the dedication of the presidential library at his birthplace in Yorba Linda, California. He suffered a serious blow last year with the death of his wife.

In his final trip abroad, last month, Nixon visited Russia and met Alexander Rutskoi, the former Russian vice president and one of the freed leaders of the parliamentary revolt, but was subsequently cold-shouldered by Boris Yeltsin, who was angry that he had met Rutskoi. In London in the succeeding week he reportedly spoke without notes at a dinner given by the Conservative MP Jonathan Aitken and for over an hour answered questions as fluently as ever from politicians and military chiefs.

There were those who had not forgotten Nixon’s political sins; but, as Watergate receded into the historical memory, America forgave him at last. Only this year a historian of the presidency noted that “President Nixon’s stock has risen sharply during the past few years”. He went on, though many would still not agree with him, that it was his personal belief that Nixon “will be reckoned among the single ‘great’ or ‘near great’ presidents”. That judgement may remain controversial: but it is the measure of Richard Nixon’s political skill and prodigious will.

Richard Milhous Nixon, politician, lawyer, born 9 January 1913, died 22 April 1994