Millennials have been the target of many jokes about their failure to “adult”. Believe the characterisation and those born between 1981 and 1996 are lazy, entitled and unreliable narcissists who prioritise avocado toast over buying a house.

The reality is quite different. This generation came of age during global financial collapse, geopolitical unrest and skyrocketing education costs. Now, 2024 data shows that as millennials approach middle age, they are struggling on multiple fronts.

Dr Kate Lycett, a research fellow at Deakin University’s School of Psychology and the lead researcher of the annual Australian Unity Wellbeing Index, says there are many reasons why we should be concerned for millennials’ wellbeing. The evidence shows that life doesn’t just feel hard – by many measures, it’s a daily battle.

How do we measure wellbeing?

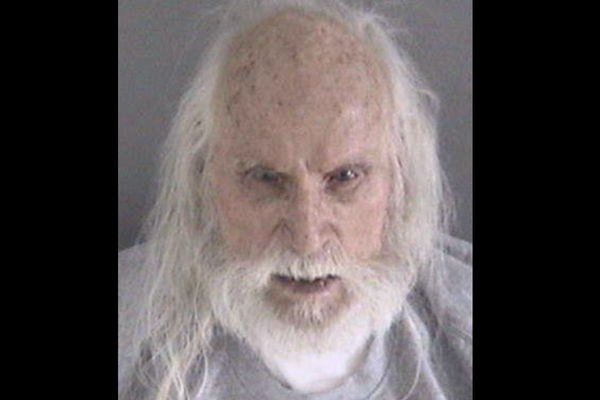

Dr Kate Lycett. Photo supplied.

The index, based on a representative survey of 2,000 Australians, focuses on personal and national wellbeing. For personal wellbeing, it examines satisfaction across seven life areas, including personal relationships, standard of living (finances) and achieving in life (sense of purpose). Over almost 25 years, Australian Unity and Deakin University have surveyed more than 78,000 Australians to track wellbeing over time.

“A good life can be measured in two ways,” Lycett says. The first is objective wellbeing, which includes quantitative elements such as income, education, employment status and measurable health outcomes. The second is subjective: measures of how we feel about our lives, such as relationships, achievements and the ability to afford what we need. There are crossovers; for instance, we can have both objective and subjective perspectives on physical health.

“They don’t always line up,” Lycett says. “Two people with the same household income can have very different perspectives in terms of how satisfied they feel about their lives, and they may have very different life circumstances, so objective measures may not tell us the full picture.”

For millennials, housing affordability, environmental crises, global unrest and the cost of living all appear to be contributors to this misunderstood generation’s disappearing optimism.

Are millennials really in a wellbeing crisis?

Australians saw a big boost in wellbeing in 2020, at the start of the pandemic, a phenomenon Lycett attributes to economic and healthcare policy interventions. “Satisfaction with the government and social conditions in Australia were at an all-time high during the early stages of Covid,” she says.

In the years since, our satisfaction with life in Australia has fallen steadily, and this year it has dropped to its lowest level since the index began. Our satisfaction with our personal lives remains really low, too. Lycett says the figures are particularly stark for younger populations.

“We asked people whether they felt better or worse off financially, compared to their parents at the same age.” The research found that about 47% of respondents aged between 18 and 54 felt worse off. Among Australians aged 55 years and older, only 22% felt worse off.

“This is a huge divide,” Lycett says. “It gets to the heart of the generational inequities that we’re seeing. We know that young people are struggling financially but also on many fronts.”

Rates of mental distress, loneliness and material deprivation paint an especially grim picture: for example, Australians aged 18-34 reported notably higher feelings of mental distress and loneliness than people aged 55 and older. In addition, millennials were the least satisfied of any age group with their ability to afford the things they needed and to save money.

“The [generational] wellbeing divide is huge.”

What do millennials wish baby boomers understood?

Lycett says the millennial stereotypes are unfair and unhelpful. “I often talk about these data with people of the baby boomer generation,” she says, “and their comment is often, ‘We had it hard too. Young people just need to get on with it.’ The idea that young people are going to be OK – the data doesn’t suggest so.”

Lycett says older generations often point out that millennials stand to inherit the most wealth in history. But, she says, this is less a reason to be optimistic than a sign of increasing inequity, as wealth is not shared evenly across older generations.

“Many people will be left behind,” she says, which will also have an impact on wellbeing. “We saw that people of all ages who are renting or in other living arrangements have much lower levels of wellbeing compared to people who have been able to buy a house, even if they had a mortgage.”

Overall, millennials – one of the largest generations in history – face an uphill battle to even come close to their parents’ financial stability, social engagement and happiness. Worse: they no longer expect to.

“This comes to the heart of societal progress, which is the idea that each generation will be better off than the next,” Lycett says. “This research is saying, young people don’t feel they’re going to be better off – and by many metrics, they’re not.

“That loss of hope is really sad.”

How can generations start to close the gap?

First, Lycett says, blaming one another isn’t helpful – we need to connect one generation to another. Second, we need policies that focus on improving younger generations’ opportunities and wellbeing.

“Some of the onus here is on older people to actually listen and try to understand young people, and not think, ‘Toughen up, sunshine’. We are living in a very different time with so much uncertainty. One only has to look at the time it takes to save for a housing deposit now to understand how different it is.

“For boomers it used to take a few years to save for an average housing deposit; it’s now estimated to take around 12-16 years. We need to understand that young people want to feel heard and supported and deserve the same opportunities as previous generations. ”

Overcoming these declines in millennial wellbeing must be, she suggests, a group effort, and Australian Unity’s chief executive officer for wealth and capital markets, Esther Kerr, agrees.

“Individually, people may not be able to achieve great social change, but collectively through community assets and resources we can,” Kerr says. “The index helps us identify where those assets and resources can help without having to wait for big policy reform.”

Lycett says it’s crucial for older generations to think beyond their own experiences.

“I think blaming the boomers is not helpful,” she says, “but given that mostly boomers hold the political and policy power, they certainly need to be working hard with young people together as a nation to try and solve this. We need good policies to lift young people up because they’re really hurting, and unless something changes, their outlook looks bleak, and nobody wants this.

“It isn’t generational warfare that young people want to be understood. We all need each other. It’s time to wrap around and nurture them.”