On a chilly Halloween night in late October 1950, dozens of Jewish teenagers and their friends gathered for merriment in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester at the Hecht House, a Jewish community center that provided job training and hosted social events. While there, they celebrated the holiday with dancing, cake and ice cream.

Then, terror approached.

Motivated by antisemitism, neighborhood teens launched a brutal attack on the premises of Hecht House that left many of the young Jews at the party injured and some hospitalized. The attackers faced no repercussions.

The assaults at Hecht House sparked community conversations about anti-Jewish violence and its minimization by local authorities, themes that resonate today given the rising numbers of antisemitic hate crimes.

Details of the Hecht House attacks remain overlooked in historical analyses about antisemitism, where outbursts like these are often discounted as sporadic or insignificant.

Yet the incident – and what led up to it and its subsequent fallout – underscore the importance of taking antisemitic extremism seriously.

Origins of violence

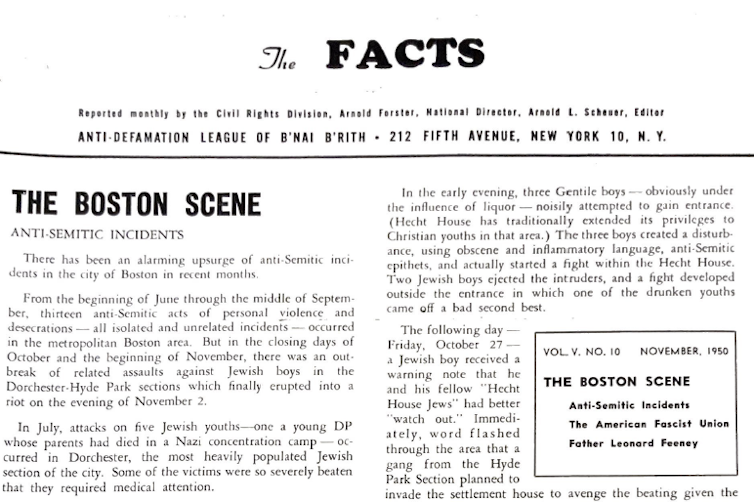

My research on the history of antisemitic radicalism in America led me to the papers of the Anti-Defamation League, a nonprofit organization that fights antisemitism and extremism, where I learned about the Hecht House attacks.

The trouble started months before the attacks, when non-Jewish teens began assaulting Jews throughout Boston, a prominent destination for Jewish people displaced by World War II.

Coupled with longtime antisemitic myths, the presence of these Jewish teens, called “foreigners” by some white Bostonians, spelled disaster for some members of Boston’s Jewish community. As I learned further in my research, new immigrants were not the only Jews to suffer violence throughout the 1950s.

Youth gangs roamed the streets shouting regularly, “Come on out you dirty Jews, we’re going to stone and kill you!”

In one incident, a group attacked a disabled Jewish war veteran incapable of defending himself. In another, they beat a Jewish refugee boy whose parents had perished in a Nazi concentration camp.

In comments to local newspapers and official reports, Boston police downplayed such attacks as symptoms of “juvenile delinquency,” blaming bad parenting and teenage mischief rather than a toxic ideology.

When the Jewish Community Council of Boston complained to authorities about the wave of youth violence, officials responded with indifference, if not outright disdain.

“Kids have always called each other names and fought,” said one official to local Jewish leaders. According to the Jewish Community Council’s records, another common response was that the Jews were “just trying to stir up trouble,” reading “prejudice into fist fights.”

Halloween at Hecht House

Days before the Halloween attack, drunken teens broke into Hecht House and spouted antisemitic slurs. A fight erupted with Jewish residents, who kicked them out.

But the drunken teens promised to eventually return and “clean up the Jews.”

At the house, a Jewish boy soon discovered a note warning that “Hecht House Jews” had better “watch out.” The Anti-Defamation League collected the facts of the encounter from the Jews involved.

When the Halloween attack finally happened, between 1,500 and 2,000 spectators gathered close to Hecht House, hoping to catch a glimpse of the action.

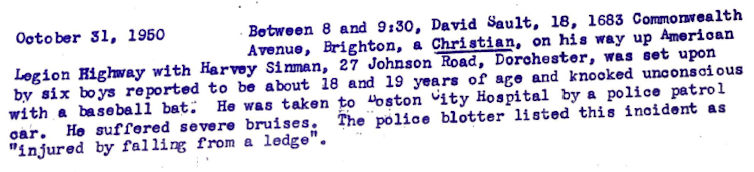

The first victim, David Sault, was a Christian friend of the Jewish residents. He tried to enter the house through a back door when six boys seized him and beat him unconscious with a baseball bat. A police report listed the incident as “injured by falling from a ledge.”

According to eyewitnesses, a gang of at least 15 assailants began a violent rampage chasing Jews from Hecht House down poorly lit neighborhood streets. They battered one Jewish boy, Milton Segal, with a tire chain, leaving him with a broken nose and cuts on his face and chest. Though he was hospitalized, Segal’s case did not appear in police records.

Two Jewish teens traveling to the party heard of the commotion and removed their trouser belts, prepared to defend themselves. Police accosted the pair and cuffed them for “being armed with a weapon,” but they were quickly released.

Two days later, when false rumors circulated within the Jewish community that a Jewish boy had died as a result of his injuries, some Jewish teenagers vowed revenge.

To avoid suspicion, they left Hecht House in small groups to confront the gang by a bowling alley. Both groups came armed with axes, razors and brass knuckles, but a policeman drew his revolver to stop the factions from fighting.

Eighteen of the 25 Jewish boys present were booked for participation in a fight, but the dozens of white Bostonians involved escaped consequences.

The violence persisted throughout the 1950s as Jews and others in the Boston community disagreed over its origins and the role of antisemitism. One writer for the Boston Herald commented that some community members might “dismiss these incidents as boy stuff and unavoidable.”

Another journalist in the Boston Traveler wrote that “the youth-gang warfare has more of the coloration of juvenile delinquency than of antisemitism.”

Boston’s police commissioner also denied that the issue was racial or religious. After the Halloween debacle, he told Anti-Defamation League representatives that “vandalism and hoodlumism” were responsible for the affronts.

The Jewish reaction

Boston’s Jewish Community Council insisted that “deep-seated antisemitic” attitudes were to blame. Nationally, the Jewish press condemned the Boston police for its inability to “cope with organized kid pogroms.”

Jews drew connections between Christian youth gangs, the antisemitic and massively popular radio priest Father Charles Coughlin, and his followers in the extremist militia group the Christian Front. Between the 1930s and 1940s, Coughlin preached anti-Jewish conspiracies to 30 million listeners each week, while his admirers in the Christian Front assaulted Jews in large cities, including Boston.

Jewish and anti-fascist activists urged citizens to recognize the significance of ideological hatred in youth gangs. They argued that attributing violence against Jews to youthful delinquency sidestepped the real issue of antisemitism.

In early November 1950, the Anti-Defamation League finally convinced Boston’s police commissioner that the Hecht House assaults were the result of “organized bigotry.”

The flare-ups in Boston peaked on a particularly frightful Halloween in 1950 and exemplify not only the brutality of antisemitism but the harms of its trivialization by authorities who downplay claims of antisemitism.

Andrew Sperling does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.