The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has now literally struck gold at Adichanallur, the largest well-preserved urn burial site in Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu.

Strongly criticised by Tamil people, particularly politicians, for “abandoning” excavation at Keeladi, near Madurai, where a Sangam Age urban settlement had been discovered, the ASI recently began its excavations again at Adichanallur.

A couple of years after the controversy, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, in 2020, announced in the Budget that Adichanallur would be one of the five iconic sites where the Centre would undertake large scale excavations to unearth a glorious past. And now, the ASI team has done that spectacularly.

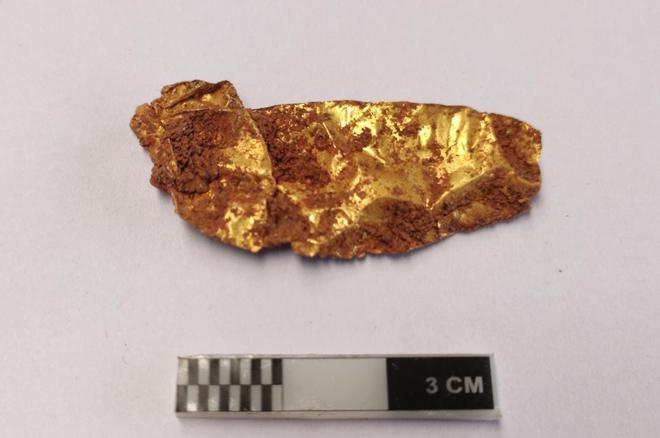

Apart from unearthing burial urns, characteristic of this Iron Age cemetery, the ASI team led by Arun Raj, Superintending Archaeologist, Tiruchi Circle, found a perfect trench where a skull of a member of a clan that lived about 3,000 years ago was buried. With that, the team has also found a gold diadem, bronze artefacts, headgear, spear, arrowheads, dog toy and paddy, all buried alongside the remains. In the adjacent trench, a small gold ring, assumed to be that of a child, was found at a depth of 30 cm itself.

It was in 1903-04 that British archaeologist Alexander Rea unearthed a treasure of over 9,000 objects here. As the terrain had changed over the hundred years since, in the ASI excavations during 2004 and 2005, the archaeologists found a lot of iron objects, a few copper objects but no bronze or gold, as they were more focused on habitations.

This time around, the ASI team studied Rea’s report carefully and found clues and then harnessed technology to zero in on the trenches to be dug at three different sites when the excavation began in October 2021.

Using Geological Survey of India (GSI) data to overlay the maps, the team went for the dig in this particular trench about a month ago. The ‘C’ site, as they call it, has about seven possible burials of the heads of important persons of the clans that existed between 500 to 1,000 BCE.

It was in the first trench that they found objects in bronze and gold similar to what Alexander Rea discovered at the turn of the 20 th Century. It was the gold diadem they were after. Rea had found 14 gold diadems. Now, they had found one, and possibly more were likely to be unearthed, when excavations continue next year.

Inland gold

Gold was an inland source from the region located north of the present northern borders of Tamil Nadu. Several gold workings are reported from the neighbourhood of the Hutti gold mines, the present Raichur district of Karnataka. Some of them have been dated to about 3,000 years ago, says Ravi Korisettar, Adjunct Professor, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.

“The granulite [charnockite] terrain in Tamil Nadu is also reported to yield gold, but how long ago this gold was exploited is not known. However, from 1,000 BCE onwards since the beginning of the megalithic or Iron Age in south India, gold was a traded commodity. Not surprising therefore that it has been found in Adichanallur,” he says.

“Sanganakallu, a Neolithic and Megalithic site near Ballari in Karnataka, has yielded gold foils but in small quantities and not from a burial context like at Adichanallur,” he adds.

“It is one of the best sites excavated after a century. All the artefacts unearthed are excellent,” says an academician-cum-archaeologist at Adichanallur, on condition of anonymity.

He expects the ASI to unearth contemporary habitation sites as the excavation progresses further. Although gold has been found repeatedly during excavations in the country, the earliest in Tamil Nadu was in Adichanallur, he says.

“The diadem, a bejewelled crown or headband, is peculiar to Adichanallur,” he notes further.

Korkai connection

Not far from the Adichanallur site, which sits at the top of a mound along Tirunelveli-Tiruchendur Road, lies Korkai, an ancient port city of the Pandya kings. At present, the sea is rough due to the monsoon winds. When the sea calms by September, the State Archaeology Department plans to look for clues connected to an ancient civilisation at this site as well.

“Around any port city, there will be satellite villages feeding it. Only then can an urban habitat survive. Adichanallur could have been one. The entire Thamirabarani river basin has to be surveyed to trace back the civilization,” says the retired academician.

T. Satymurthy led the excavation here in 2004-05 as Superintendent Archaeologist, Chennai Circle. He says, “From what it looks like now, we can’t imagine the Adichanallur of 3,000 years ago. Then the Thamirabarani could have been 2 km wide, and the ships could have come up till the present site itself.” The previous ASI report on the 2004-05 excavations led by him was released in 2021, 15 years after it was ready. Prepared by Sathyabhama Badhreenath, the report has some interesting findings about the people of Adichanallur.

Maritime trade

On the whole, the Iron Age cemetery of Adichanallur has yielded wonderful information on many branches of bioarchaeology, biological anthropology and social archaeology, the report states.

The Bio Report 1 of Raghavan Pathmanathan on ‘The General Pathological Abnormalities of Adichanallur’s Pre-historic Humans’ showed the presence of various races during the Iron Age period at the sub-coastal, prehistoric harbour town at Adichanallur.

Associated materials along with the burials have yielded vital clues for maritime trade activities at the southern rim of the Indian Ocean.

Recoveries of many Tamil cultural artefacts in Vietnam, Cambodia and other South East and Far East Asian countries right from the Iron Age till early 17 th Century prove that there were aggressive free sea trade activities that flourished for a long time.

According to the report, the results on pathological skeletal and dental abnormalities were amazing as such abnormalities had never been reported from anywhere else so far. Information on epigenetic variants, genetical pathology and osteogenesis may contribute significant clues in the field of evolutionary genetics and the various factors of stress and strain that operate upon the sea voyagers and settlers of Iron Age India, the report states.

The recovered skeletal biological data, however, was insufficient to draw a genuine conclusion on the structure of the ancient community. Therefore, physical anthropologists, archaeologists, geologists and prehistorians should systematically excavate (study) this area, the report concludes.