What do a finger bone and some teeth found in the frigid Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai mountains have in common with fossils from the balmy hills of tropical northern Laos?

Not much, until now: in a Laotian cave, an international team of researchers including ourselves has discovered a tooth belonging to an ancient human previously only known from icy northern latitudes – a Denisovan.

The find shows these long-lost relatives of Homo sapiens inhabited a wider area and range of environments than we previously knew, confirming hints found in the DNA of modern human populations from Southeast Asia and Australasia.

Read more: Fresh clues to the life and times of the Denisovans, a little-known ancient group of humans

Who were the Denisovans?

Little is known about these distant cousins of modern humans, except that they once lived in Asia, were related to and interacted with the better-known Neanderthals, and are now extinct.

The first traces of Denisovans were only found in 2010, with the discovery of an innocuous finger bone in remote Denisova Cave. The extreme cold of the cave meant some ancient DNA was preserved in the bone – and the DNA revealed the finger had belonged to an unknown species of human.

This discovery changed the course of human evolutionary studies, and the newly discovered humans were named Denisovans after the cave where the fossil was found.

Fossilised teeth from Denisovans were later discovered in the same cave. Two upper and one lower molar were found in sediments that were dated to between 195,000 and 52,000 years ago.

Meanwhile, it was found that genes from Denisovans survived in modern day people from Southeast Asia and Australasia. This implied that the Denisovans had dispersed over a far larger area than anticipated.

Read more: Evolutionary study suggests prehistoric human fossils 'hiding in plain sight' in Southeast Asia

The hunt for more fossils

The hunt was on to find more evidence of these humans outside Russia, but scientists had no idea what they actually looked like. For the first time in history we knew more about a human’s DNA than their anatomy!

The next twist came when a 160,000-year-old Denisovan jawbone surfaced on the Tibetan Plateau, giving the scientific community a tantalising glimpse of what the bodies of these ancient humans were like and where they lived.

But questions remained: just how far did they spread in Asia, and how did their genetic imprint survive in Southeast Asians and Australasians?

Clearly Denisovans could live in the cold environments of Siberia and Tibet, but could they have also occupied a completely different ecological niche and adapted to a tropical climate?

Tam Ngu Hao 2 (Cobra Cave)

Enter a new cave found by an international (Laos–French–American–Australian) team in northern Laos in 2018, close to the famous Tam Pa Ling cave where 70,000-year-old modern human fossils were found.

The site, named Tam Ngu Hao 2 (or Cobra Cave), was found high up in the limestone mountains and contained remnants of old cave sediment packed with fossils.

The cave sediments contained teeth from giant herbivores, such as ancient elephants and rhinos that liked to live in woodland environments. The teeth were likely washed into the cave during a flooding event that deposited the sediments and fossils.

These sediments were covered by a layer of very hard rock called flowstone, which is formed by water flowing over the cave floor. The sediments and fossils were dated by this study to provide an age for the time of deposition in the cave, and by association a minimum age for the death of the animals.

A young girl’s tooth

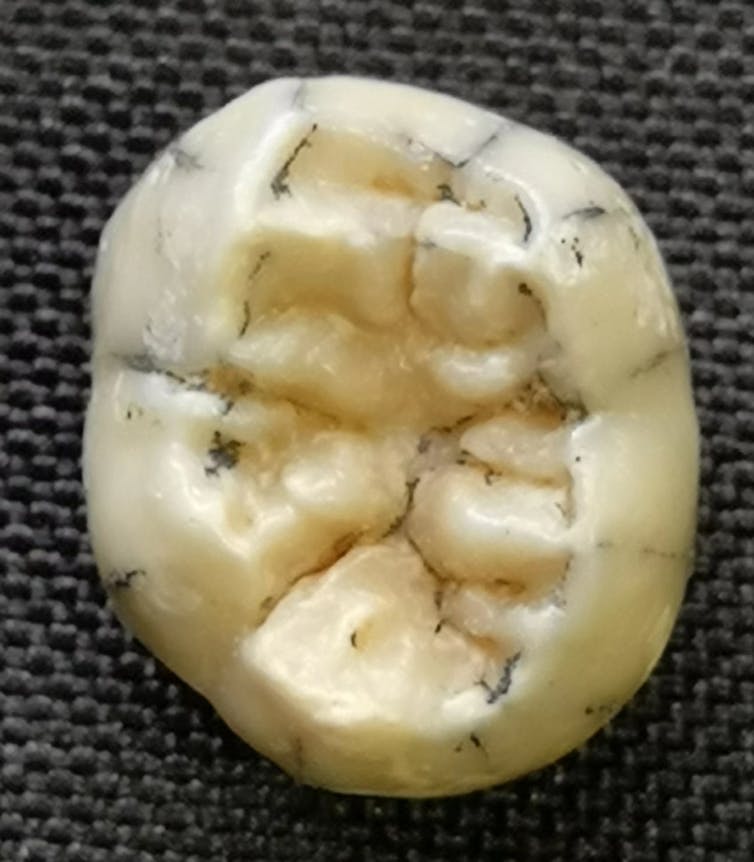

A human tooth (a lower permanent molar) was found in the cave sediments, but we could not initially identify what species of human it came from. The humid conditions in Laos meant that the ancient DNA was not preserved.

We did however find ancient proteins that suggested the tooth came from a young, likely female, human – probably between 3.5 and 8.5 years old.

After very detailed analysis of the shape of this tooth, our team identified many similarities to the Denisovan teeth found on the Tibetan Plateau. This suggested the tooth’s owner was most likely a Denisovan who lived between 164,000 and 131,000 years ago in the warm tropics.

An ancient human hotspot

This fossil represents the first discovery of Denisovans in Southeast Asia, and shows that Denisovans were at least as far south as Laos. This is in agreement with the genetic evidence found in modern day Southeast Asian populations.

They may have been just at home in the balmy tropical climates of Laos as the icy conditions of northern Europe and the high-altitude environments of the Tibetan Plateau. This suggests the Denisovans were very good at adapting to diverse environments.

It would seem that Southeast Asia was a hotspot of diversity for humans. At least five different species set up camp there at different times: Homo erectus, the Denisovans/Neanderthals, Homo floresiensis, Homo luzonensis, and Homo sapiens.

How many of these species overlapped and interacted? Another fossil discovered in the dense network of Southeast Asian caves could provide the next clue to understanding these complex relationships.

Kira Westaway receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the Leakey Foundation

Mike W Morley receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Renaud Joannes-Boyau receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.