The fridge in the entryway of Walt Wells’s campus office was empty. Thomas Bowling, Eastern Kentucky’s director of football operations, noticed it on his way out the door on a late August evening.

At the top of Bowling’s to-do list when he arrived the next day: get his boss some Powerade. The next morning, with the Colonels’ season opener against Eastern Michigan just five days away, Bowling waited for Wells to get to the team facility as other coaches dived knee-deep into the work of game-planning.

“He went into his office and started working, and I started filling up his fridge,” says Bowling, who also played for EKU and was on the roster when Wells took over in 2020. “I was about done, and it sounded like he sneezed almost. I always ask him if he wants me to shut the door. So I didn’t go in yet. I was like, ‘Coach, you want me to shut the door?’ He didn’t answer, and that’s when I peeked in and I saw him there.”

But the noise Bowling heard was actually Wells dropping to the floor—the coach was having a heart attack.

EKU Athletics

Bowling ran out and told an assistant coach to call 911 while he phoned athletic trainers Kristen Peterson and Zach Vigliotti, who both rushed upstairs from the athletic training room to attend to Wells. They expected that maybe the coach had missed breakfast and fainted, but the reality was much worse. They rolled him over, hooked him up to an automated external defibrillator machine and started performing CPR. He was pulseless and was not breathing.

“At that point, I left the room,” Bowling says. “I was a little shook up and I actually called his wife, which was probably one of the hardest things I had to do because Miss Jen is such a sweet lady. I don’t think she realized the extent of what was going on, and then she called me back and she asked me if he was gone, and I was like, “No, Ms. Wells, they’re doing CPR.”

Peterson received the phone call at 10:01 a.m., and paramedics arrived by 10:14. Bowling and other coaches were outside helping to direct the EMTs through the building up to Wells’s second-floor office. Peterson made sure Jen Wells and the Wells’s two children were shielded from seeing what was going on when they arrived while Vigliotti continued to help the EMTs.

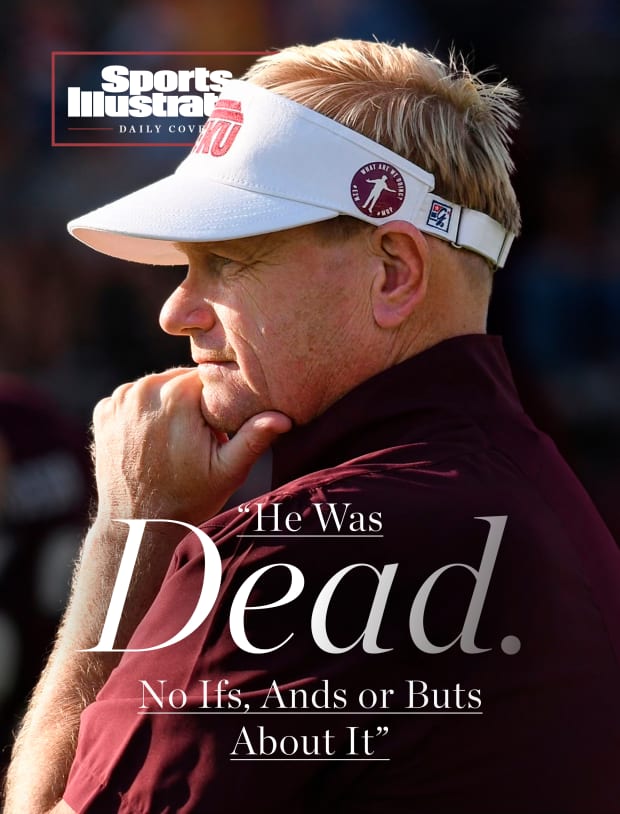

“He was dead,” Jen recalls. “There was no ifs, ands or buts about it.”

EKU Athletics

Heart attacks sometimes come after a few warning signs, perhaps tingling in an arm or chest pain. Wells had neither. He doesn’t remember anything that happened. While Bowling was stocking his fridge, he was trying to get a box together to send to his 90-year-old mother.

The next thing he remembers is waking up in a hospital bed.

When he arrived at UK Hospital in Lexington, doctors found a 95% blockage to the main artery in the front of Wells’s heart, informally referred to as the “widowmaker.” Rather than performing open heart surgery, doctors went in through his wrist with a catheter to place a stent in the artery all the way up to his heart, effectively working like a scaffold to hold the artery open in the future.

“He had a pretty long blockage, which was also calcified, which means [this attack has] been brewing for a while, so he’s probably had some buildup of blockages,” says interventional cardiologist Amartya Kundu, the head physician who treated Wells. “It took us a few hours to work our way through it. We had to use some special equipment, but in the end, we had a pretty good result.”

But the subsequent days were crucial for the 54-year-old Wells, who was put on a ventilator as soon as he arrived at the hospital to protect his airways until doctors were certain he could breathe on his own. Initially, the medical team told his wife he might have sustained damage to his heart, kidneys or brain. Due to the decisive acts of all involved—in Kundu’s words, Peterson and Vigliotti “brought him back”—the coach avoided any organ damage, including to his actual heart muscle. It was “miraculous,” according to Kundu, who ballparked someone in Wells’s condition leaving the hospital alive at around 20%.

Courtesy of The Wells Family

To try to coax Wells awake, his son, KJ, played music from Guns N’ Roses (Walt’s daily alarm) and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird.” His daughter, Maddie, recited to him the coachspeak of “Pain is weakness leaving the body.” The stubborn coach also showed signs he was fighting while under sedation. His reflexes stayed sharp and at times attempted to pull the vent out of his throat.

“At one point, opened his eyes and looked straight at me,” Jen says. “Then [the nurse] goes, ‘Do you see, Jen?’ He looked at me, and I thought, ‘I don't think he has brain damage.’ … I had to be pretty strong for my two kids, because they kept looking at me. ‘Is he going to walk me down the aisle? Is he going to see me graduate?’ I don't usually fall apart because somebody has to keep it together [since] he couldn’t obviously, so I just guess I processed and I compartmentalized, but it was scary.”

After about 48 hours since he had collapsed in his office, he was awake, alert and breathing on his own. He woke up to 1,200 text messages and 400 emails. He tried his best to respond to all of them.

“They asked me what I wanted when I woke up, and I said, ‘I need a beer and a cigar,’” Walt says. “I haven’t smoked a cigar yet, so we’ll see how it all goes. We’ll chew on ’em, maybe.”

By Sept. 1, Wells was able to walk out of the hospital, the day before the Colonels were set to face Eastern Michigan in Ypsilanti. And, to the surprise of both him and Jen, doctors didn’t prescribe many restrictions beyond not lifting heavy objects and a caution about overexerting himself. Wells had dealt with atrial fibrillation (a condition causing an irregular heart rhythm that can lead to clotting) in the past and has a significant family history of heart disease. His father and uncle both died from heart-related issues, while his brother has had a quintuple bypass. “So,” Wells explains, “you kind of figure it’s coming.”

Given that he was well into his 50s, and his mother was in her 90s, he thought maybe the bad side of his family history skipped over him. A former offensive lineman, he dropped nearly 100 pounds in the early 2000s and had been going to yearly checkups since he was in his 30s.

“He looked at me in the hospital and just said, ‘Thomas, did you save my life?’ And I was like, ‘Coach, I tried my best,’” Bowling says. “It was a pretty emotional moment for both of us. Then I told him, ‘Coach, your fridge was empty. I had to fill that thing up.’”

While Wells continued his recovery, Eastern Kentucky tried to reestablish a sense of normalcy heading into the game against Eastern Michigan.

Football chief of staff Garry McPeek was on his motorcycle when his Apple Watch started buzzing. He arrived at the team facility as the EMTs were working on Wells. After they left for the hospital, there was the question of what exactly to do.

The coaching staff consulted with the players, and the decision was made to continue on with game prep and a practice that understandably featured a team focusing on things beyond football. What eventually got everyone into gear was a belief that their head coach was going to return.

“Coach Wells eventually is going to cut this film on, and it would be a shame if whatever we put out there is not going to be up to his standards … and the standards of the team,” veteran defensive lineman Shane Burks II says. “We have core values and we live by those. Every single day we talk about them, so [we had to be] able to live up to what we talk about no matter what’s going on. Through it all, we tried our best to stay positive. I tried to stay positive as a leader myself.”

McPeek took over as acting head coach, a purposeful title given by athletic director Matt Roan that made it clear Wells was going to eventually be back. McPeek had been a high school head coach and administrator before arriving at EKU, and has known Wells for 25 years. The AD also tried to make sure no assistant coaches had too many extra responsibilities. The situation was somewhat similar to what coaches and players had to deal with during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when a coach could be out for a few games due to illness.

Director of Athletics Communications Rixon Lane was tasked with readying statements for various scenarios, but he couldn’t bring himself to think he’d have to write one announcing Wells had passed away. The team received daily updates on Wells’s status after practice and any developments were relayed to players before the school released anything to reporters or social media.

Emily Muse/EKU Athletics

Wells’s game-day location for the clash against Eastern Michigan was also different: He sat on his couch, next to his wife, who was doing some coaching of her own.

Walt: “Why are they doing that? He just missed this route!”

Jen: “You do not need to get excited. Calm down.”

“I’ve never done that before,” Jen says. “I’m sure their phones were blown up when they got off the field. … It was different watching it with him because it was his team, and he was watching it in real time, so that was an experience I’ve never had before. But he kept up with it, I’ll say that.”

The day afterward, and six days since he very nearly died in his office, Wells did what he always does after a game: He went in to watch the film.

“Seeing the players was good for me; it’s good for my heart—not my heart health, but my mental health, my well-being. Some of them were like they’d seen a ghost,” Wells says. “‘Coach, what are you doing?’ I don't have anything else to do, you know? I came here to watch the film. … I want to sit there and have my notes ready for the coaches when they get in. I could tell right then it was a different type of watch. Little things didn’t blow my gasket.”

He is also using his experience to jokingly add a little levity now that he’s back with the team. He tells Peterson he’s “built different,” and now his players don’t have an excuse to sit out.

“I’ve told them you can’t let a little hamstring keep you out,” Wells says with a laugh. “‘I was just on the floor dead and I’m here working. I missed one game.’ I kind of mess with them on that, but they look at me like, ‘You’ve got a point.’ It’s all in fun, but I think it’s been an eye-opening experience for them.”

Bowling admits it’s still hard to get the picture of what he saw that day on Aug. 28 out of his head. It was important for him to see Wells as soon as he could, and he was there on the day Wells woke up in the hospital. What sticks with people involved that day are the “what-ifs” and how to grapple with real trauma. Resting on faith is a natural way to process what happened as Peterson and Vigliotti talked to each other in the training room. They’ve both always believed in a higher power; it’s fair to say that’s been strengthened.

“I don't know if you remember it,” Peterson says to Vigliotti, “but I was doing compressions and I was like, ‘Jesus, please help this man live. God, please help him live.’ Because I mean, he’s dead. I was like, ‘Please help this man live.’ … ‘Please do something.’ And He did. There’s no other explanation.”

Wells says he has been asked by countless people whether he had seen the light.

“I’ve been asked 100 times about that. I did not realize that was such a big deal,” Wells says. “I have been asked by players, coaches, friends, former players. A guy last night, he goes, ‘I’ve got to ask. Did you see a light? I’ve got to know.’ And I’m like, ‘Dude, if you’re trying to save your soul on the fact that I saw a light, then you better reassess that.’”

What if Wells simply wasn’t in the office at the time it happened? What if Bowling had forgotten to stock the fridge or didn’t have a need to at all? What if he didn’t knock on Wells’s closed door or left when he didn’t hear an answer, which staffers say is what they normally do, assuming the coach was hard at work? What if Peterson didn’t answer the phone since multiple calls from Bowling aren’t rare during a normal day? And, most crucially, what if the trainers weren’t even on campus at all?

While high-level FBS teams have large athletic training staffs, the size can vary across levels of the sport. Alcorn State had to cancel practices because they didn’t have training staff on hand. The National Athletic Trainers’ Association released a study in 2019 that showed 34% of public and private high schools in the country (nearly 7,000) did not have access to athletic trainers for its athletes.

“I think our profession is very undervalued in what we do,” Vigliotti says. “People think we are just here to tape ankles and hand out water, and we run out on the field and get people off the field, but they don’t see the behind-the-scenes stuff we do and all the training that we go into. We’re considered an allied health profession; we have to take 50 continuing education credits every two years. Most professions take 20 every three years.”

They also had access to the needed equipment. There are AEDs throughout Eastern Kentucky’s athletic facility that are regularly serviced. While the trainers and EMTs treated Wells, the device recorded his heart activity, and the data was shared with his cardiologist. The trainers were prepared for an emergency medical situation and how to use the devices. They did not think but rather simply reacted and started CPR within minutes. Peterson estimated that if Wells’s heart had been stopped for any more than about five minutes, he wouldn’t be here right now.

“[Thomas] could’ve walked out the door,” Wells says. “And if he had walked out the door and I had just laid there, they would have come back, and I would have been cold as a cucumber, just laying there. For him to have the discipline, the consistency to walk in to see if I needed anything else, to just check on me to see how I was doing and then see me laying there on the floor, it shows what kind of person he is.”

After his team’s seven-overtime victory against Bowling Green, in a game he did not coach, Walt Wells came close to expressing emotion in a way he rarely does. His voice trembles and his trademark visor shakes in his hands as he holds on. He was taught not to cry, but he gets close during the postgame speech to his team.

It was more than the emotions from the theatrics involved on the field that night. For Wells and others in the program, the fact that he stood in front of them is what many describe as a miracle considering what had happened two weeks ago.

“Sometimes at night, I do touch him to see if he’s breathing, and then one night I put my hand on his chest and he woke up and he goes, ‘What are you doing?’” Jen says. “Other than that, and I think I’m bugging him, because I keep going, ‘Are you O.K.?’ And if he moves, I’m like, ‘Are you O.K.? Are you O.K.?’ So that’s been the majority of it, but I feel like we’re really blessed and that it just wasn’t the time yet.”

He spent his first week back on the job largely on a golf cart, off to the side, before the Bowling Green game Sept. 10, which he joked was a good test of how well his heart was working. His chest is still a little sore from the compressions and he says he’s easing himself back into things, but opinions differ among staff and players around how successful his efforts really are in terms of slowing down along the sidelines. His first full game back, with his headset on calling the shots, showed he had plenty of fire left in a comfortable win against Charleston Southern. His heart monitoring device was removed the day before that game, and he is continuing to go to cardiac rehab. Although it’s safe to say he’s significantly far along in at least one aspect of his recovery.

“They hook me up, get a monitor on me to an EKG thing, and [my physical therapist] goes, ‘All right, now we’re going to walk for six minutes. Have you done anything physical?’ and I say, ‘Yesterday at practice I got 6,000 steps and I walk up the steps coming to the second floor probably 15 times a day.’ He kind of looked at me and then he figured out who I was.”

Sports figures are often celebrated for making big plays or winning dramatic games, but true acts of heroism are found off the field or when the stadium lights are off. For Wells to coach more games and celebrate more wins in the locker room with his team, regular people had to act on a regular Sunday morning that quickly turned into anything but.

Football and life keep on moving. Thankfully, Walt Wells is still here to experience both.