Fiordland National Park is the crowning jewel of our national parks and arguably our greatest tourist magnet. But conservationists warn that marine life has been put at risk because the park’s waters are unprotected. Heidi Bendikson’s investigation shows they are right.

Tourists on the 'M.V Sinbad' clamber to the bow to take a photo of the waterfall on the edge of Doubtful Sound.

When Fiordland’s glaciers retreated, the sea took its place. Surrounding mountains, towering up to 2000m above sea level, still bear the glaciers’ scars. Ice melt and rainwater collect tannins from the forest foliage before cascading down the cliffs.

The result is a tea-coloured layer of freshwater which filters light, creating an illusion of depth allowing rare black coral, usually restrained to deep waters, to thrive at diveable depths.

READ MORE: * Money v nature in Milford Sound * Sea life suffers as cars hit the beach * Black Sand Highway: Sea lion vs traffic

Bottlenose dolphins breed here, carefully timing their mating to ensure their babies survive in the freezing waters.

Many - from UNESCO to visiting politicians, as well as prominent conservationists - have asked the same question: why is this fragile and unique ecosystem not part of the Fiordland National Park?

Anyone who asks is usually given the same answer – they have never been part of a national park, it cannot be done. But that is not quite right.

***

If any one person embodies the fight to put the fiords back in the park, it’s Lance Shaw.

Sitting in his lounge in a Sea Shepherd t-shirt in his small house at the edge of Fiordland, Shaw is never short of an expletive when it comes to describing the lack of marine protection in the fiords.

With his wife Ruth, he has tirelessly advocated to protect Fiordland’s marine treasures from destruction by uncontrolled fishing.

“Everybody in New Zealand should know that the biggest national park is without the fiords.”

Shaw might be described as a “poacher-turned-gamekeeper”.

He spent four years as a crayfisherman in Fiordland before becoming a park ranger, manning Department of Survey and Land Information (DSL) vessel The Renown to monitor the park and assist visiting scientists.

He remembers vividly the day DSL was replaced by DoC. It was 1987, the year of New Zealand’s National Park Centennial, yet the park ranger service was being disbanded.

He watched his fellow rangers, many gnarly after years of service in the rugged bush of Fiordland, break down in tears as they packed their belongings.

Shaw had escaped the redundancies, but his title changed – from park ranger to conservation officer. A new uniform arrived for him – fresh pressed and bearing the green DoC logo. New DoC signs were erected at every junction, every building.

He’d been told the restructure was about saving money, but it was being spent everywhere he looked.

Shaw remembers glancing at the uniform before shoving it into a drawer. Eventually, he became too green for the DoC shirt, anyway.

When he spotted a letter in the DoC workshop saying staff were not allowed to advocate for marine reserves, it was the final straw and he left the position to set up a water-based eco-tourism business with Ruth.

Throughout the 1990s, they continued to advocate for the fiords being included in the park, writing letters to DoC and members of Parliament.

In the late 1990s in response to Lance and Ruth’s letters asking DoC and politicians why the fiords were not in the park, they started getting replies saying they could rest assured, “marine protection was coming”.

What very few Kiwis know is that the protection used to be there, until the Government took it away.

Wind back to 1952: in Fiordland, the park’s rangers are getting worried.

There is a crayfish boom on, and fishing boats are pouring into the fiords to plunder the white gold. They need bait. Armed with rifles, they start shooting up the park – seals, penguins, birds, deer – anything that moves.

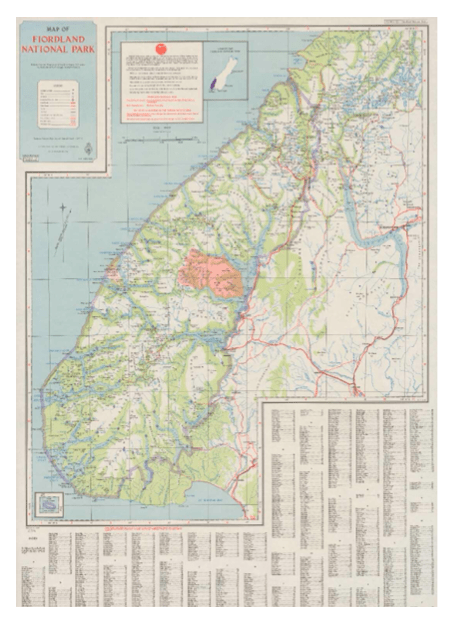

The Parks Board tries to prosecute, but are advised by the Government’s legal drafting office they do not have the power to do so. Despite the boundaries of the map, they say the marine areas of Fiordland are not part of the park.

The director-general of lands sought to rectify the matter, sending a draft amendment of the National Parks Act to the minister of lands, explaining there was a conflict between the map of the park (which cuts across the mouths of the fiords) and the written description.

The Marine Department – which managed fishing and boating regulations at the time – was consulted. It claimed to be “sympathetic” to DSL’s concerns, but resisted its efforts at every turn. The secretary of marine wrote to the director-general:

“I am not happy regarding the effect the proposed clause may have on the rights to fish and navigate in these sounds.”

Eventually the Marine Department got its way. In 1978, the same year precious black coral was discovered in the fiords, the matter was laid to rest, by an Order in Council. The national park was redefined to end at the mean high water mark.

It was the nail in the coffin for any argument the fiords might be part of the national park and they were to remain without any protection for more than 25 years.

***

Meanwhile, pressure on wildlife increased; lobster fishers kept plundering the rocks and canyons, raking through the black coral; tourist boats surged through fragile dolphin breeding pods; cruise ships ploughed up and down the sounds.

Years of pressure from Lance Shaw and others led to acknowledgement that more protection was needed.

The Guardians of Fiordland, an industry-led group of fishers, iwi representatives and scientists who devised their own management plan and Fiordland’s first marine reserves - was established and eventually enshrined as a statutory advisory group – Fiordland Marine Guardians (FMG) under the Fiordland Marine Management (Te Moana o Atuwhenua) Act 2005 (FMMA).

***

Dr Rebbeca McLeod says she was critical of the FMMA at first. She was a student studying marine biodiversity at the time, “That was the way scientists are trained to think”. But now, as FMG chair, her perspective has changed.

“It is such a remote place that, if we want people to abide by rules and regulations that are established, we need them to buy into the reasoning behind those rules and regulations and be supportive of them. It’s all about building that community and that’s really why the Fiordland model has been successful.”

The fiords’ big success story was the return of rock lobster to the fiords – something even Shaw acknowledges is quite extraordinary.

The created Fiordland Guardians model has been lauded, nationally and internationally, but Sue Maturin, the Forest & Bird Otago Southland regional manager when FMMA was enacted, was disappointed,

“We wanted much more extensive reserves and the outer coasts as well as the entrances protected.”

“The Act said there would be a review in 2010 and they did do a review, but they didn’t really look at the effectiveness of the marine reserves, which we would have expected in the marine review. We think we still need to do a review of the effectiveness of the size and location of the marine reserves.”

Maturin acknowledges the work done by FMG and their philosophy among stakeholders for “give and take”.

“But from nature’s perspective, they have given more than they have gained.”

FMG’s current concern centres on recreational fishing, particularly charter boats. While commercial fishing works to a quota, recreational fishing is less predictable, and growing.

“What we are left with is a particular sector in New Zealand fishing that we don’t have good data for. It is hard to make good decisions without the data,” Lawson says, adding that an increase in the size and number of recreational vessels, and their technology, has enhanced their impact over recent years.

But Ian Carrick, Southern Sport Fishing Club member and Fiordland Recreation and Conservation Trust trustee, says recreation fishers are unfairly targeted based on anecdotal evidence.

“We don’t go in to ... pillage, we go in to enjoy the whole experience," says Carrick.

Fishing is not the only activity impacting the fiords. Non-charter tourism boats operate out of Milford and Doubtful sound and the region is a popular detour for cruise ships.

In 2001, fewer than 30 cruise ships visited Fiordland. By 2019 that figure exceeded 130.

With each boat comes the risk of oil spills, invasive species and marine mammal strikes and disturbances.

***

Tourists on the M.V Sinbad return to the bow to take a photo of the waterfall. A lone shag sits beside the gushing water. It is the only wildlife the tourists have encountered on the trip so far, but that is not to say it is not there, dolphins with complex sex lives may be just around the corner.

Tourism operators once actively sought the seals and dolphins that made Doubtful and Milford home, trying to compel them to put on a show. But the impact from doing so could be disastrous.

Professor Steve Dawson from Otago University’s Department of Marine Science says Fiordland waters are coldest in spring when ice melt flows into the fiords, so dolphins born in January are most likely to survive. If calves are born any other time, even in February, it is too late. They will still not have sufficient insulation to protect them from the icy waters come spring.

While this may seem a random birth month lottery, Dawson says a third of the Fiordland bottlenose dolphins have realised that January is the best time to birth and they ensure that this is the case.

“So they literally decide when to start bonking,” Dawson says.

With so much riding on copulation at the correct time, it is vital the dolphins' pod behaviour is not artificially disturbed, but this is exactly what happens if boats get too close.

Dawson is aware of one charter boat that used to charge right through a pod. Others would intentionally steam around the dolphins at speed in order to generate enough wake so they would “surf”.

“This would split the group because the young thrill-seekers would go in and ride the stern wave and jump out and put on the show. And the mums and calves would head off in the other direction because that’s not the kind of scene that they wanted at all.”

Research into dolphin’s spatial awareness within the fiords led to voluntary marine mammal management guidelines in Doubtful Sound.

Dawson describes them as the best example of operator-led regulation he has seen, especially for those operators who adopted the guidelines into their corporate code of conduct.

However, the code is voluntary and, despite the efforts of FMG and DoC, not all vessels may be aware of it and there is no single entity monitoring the number of boats in the fiords.

Last year, Environment Southland resolved to pause Fiordland surface water consents until they have updated the Regional Coastal Plan to maintain the area’s wilderness values. However, cruise ships are not included. Nor are commercial and non-charter recreational fishing vessels, which are governed by the Ministry of Fisheries (MAF) – an institution which, much like its predecessor, the Marine Department, is focused on fishing interests. Sustainability over biodiversity.

Has the guardian model really worked? Would it be easier if the waters were simply part of the national park, as they originally intended to be?

***

Green Party Member of Parliament and former conservation minister Eugenie Sage says the fiords’ exclusion from the park is problematic.

She adds that regional councils are generally reluctant to restrict fishing to protect biodiversity, even though the courts have found they may do so.

“That I think is just symptomatic of our failure to recognise our marine environment generally, for the diversity of its habitats, endemic marine species, Aotearoa’s importance as a hotspot for seabirds and for how much damage we are doing to the oceans through commercial fishing, recreational fishing pressure in some areas, poor land management and sediment inflows and plastic pollution.”

But even if the Fiords had been part of the national park, would they have fared any better?

Perhaps Glacier Bay, Alaska, provides an answer. Its marine areas are part of the national park and a world heritage area. Although marine conservation was largely ignored until the 1980s and commercial fishing continues, there is one management entity monitoring the number of vessels in the waters – unlike in Fiordland – which is crucial for their world-famous humpback whales.

Notable too is the international and national recognition world heritage status gives to Glacier Bay’s marine areas.

When Fiordland was inscribed as a world heritage site, the world heritage committee recommended that the waters and seabed come under the control of park authorities.

Fiordland’s marine areas were added to the world heritage tentative list in 2007, but have not been nominated and New Zealand’s Minister of Conservation, Poto Williams, says there are no plans to do so.

“The current focus of conservation efforts for Te Wahipounamu World Heritage Area has been on improving the management of existing sites, including working in partnership with tangata whenua.”

Cabinet papers from 2007 note that eventual inscription as a world heritage site would put New Zealand under an obligation to undertake appropriate management of the site.

Representatives from Ngāi Tahu declined to be interviewed on the matter, but their media liaison pointed to a recent press release which said: “Ngāi Tahu and the mana whenua panel do not support expanding the National Parks within our takiwā. The National Parks Act restricts Ngāi Tahu from undertaking our kaitiaki rights and responsibilities, while limiting the meaningful involvement of Ngāi Tahu in decision making.”

Maturin thinks the discussion around including the fiords in the national park makes for an “interesting bit of history”, but is not what they really need. She would rather see enhanced protection of marine life through the mechanisms already in place - the marine reserves, but larger.

It is unclear at this point what a national park over a marine area would mean. The National Parks Act 1981 does not acknowledge such a thing.

With Fiordland representing 40 percent of New Zealand’s rock lobster exports, an annual export value of around $350 million, it is unlikely there would be much appetite for restrictions on commercial fishing.

As for Lance Shaw, he is not overly concerned about what bureaucratic process is used to protect the fiords.

“I think national parks are good because quite apart from anything else, it kind of just says ‘Hands off’.

“If that is too much to ask, could we have a very strongly graded marine reserve? Covering all of the fiords, not just bits. Because at the moment they’re just picking a few bits. And people are saying, Well isn’t it wonderful, you know. Well, it's a step in the right direction.”