Once upon a time, there was a real-life planet right where Star Trek put its fictional world of Vulcan — or so we thought.

Astronomers announced in 2018 that they’d discovered a planet orbiting nearby star 40 Eridani A, the fictional homeworld of Star Trek’s Spock and Project Hail Mary’s Rocky. They couldn’t see the planet, because it didn’t cross in front of its star at an angle visible from Earth; instead, they based their conclusions on what’s called radial velocity: the way 40 Eridani A’s light shifted, as if the star were wobbling under the faint but insistent gravitational tug of an orbiting planet. But according to a recent study, what looked like a planet at first glance turns out to be just an optical illusion created by starspots.

Astronomer Abigail Burrows, formerly of Dartmouth College, and her colleagues published their work in The Astronomical Journal.

The Planet that Never Was

By breaking the light from 40 Eridani into the individual wavelengths that make it up, Burrows and her colleagues realized that the star wasn’t wobbling back and forth en masse. Instead, some patches of the star’s surface are hotter and colder than average, so they shine in different wavelengths of light. As the star rotates, those patches move in and out of view, creating the illusion that the star itself is wobbling — sort of like a flipbook animation.

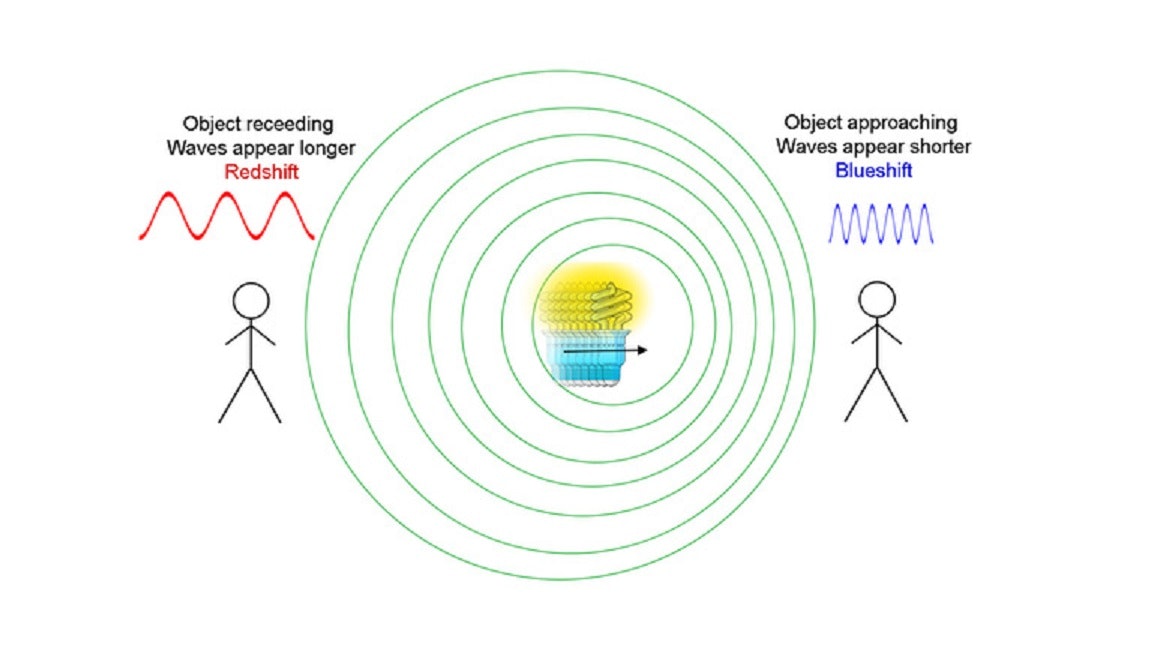

We think of planets as orbiting stars — but actually, a planet and its star orbit a shared center of gravity. Because stars are thousands of times more massive than planets, the center of gravity ends up much, much closer to the star’s center than to the planet. It’s often somewhere inside the star, so the star doesn’t really orbit so much as wobble around it (picture how a person’s hips move when they’re hula-hooping, then imagine that person is actually a giant burning ball of gas). Astronomers can often see that wobble from Earth: Evidence that a star has a planet, even if we can’t see the planet itself.

That’s thanks to the Doppler Effect, which means that as a shining object moves toward us, the light it emits is squashed into shorter waves, which look bluer; as the object moves away, the wavelengths of its light stretch, so they look redder. Back in 2018, astronomers looking at 40 Eridani A noticed that its light turned bluer, then redder, about every 42 days, as if the star was hula-hooping under the subtle influence of an unseen planet.

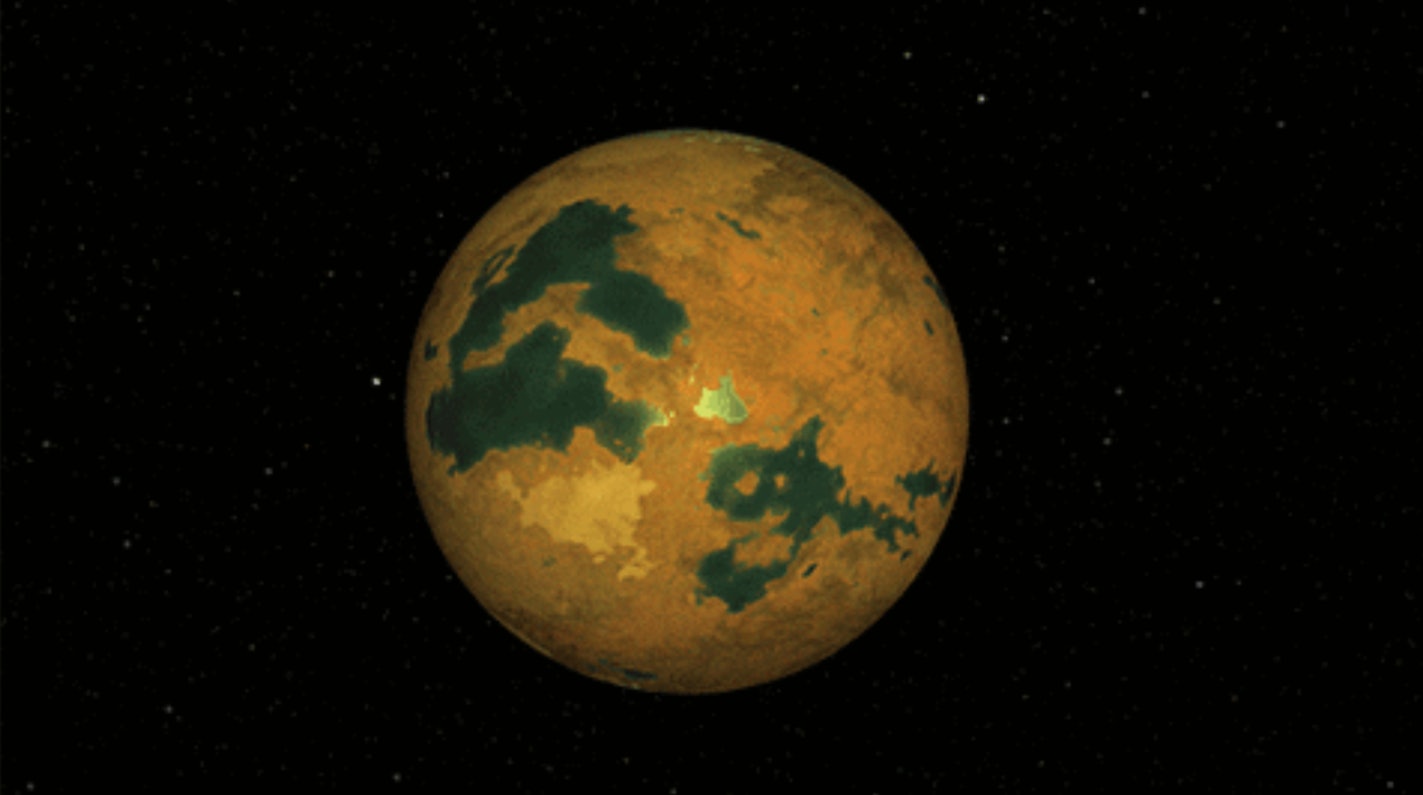

Science fiction fans rejoiced, since 40 Eridani A is the home system of Star Trek’s Vulcans, as well as Project Hail Mary’s Eridians. The planet, formally called HD 26965 b, or 40 Eridani A b, depending on which stellar catalog you’re using, quickly got the nickname Vulcan. Based on the speed and size of the star’s wobbling, astronomers calculated that Vulcan is a planet about 8 or 9 times more massive than Earth, which orbits its star every 42 days. That would make it a steamy world a little more than half the mass of Neptune.

There’s just one problem: It doesn’t exist.

“Messy Stellar Jitters Masquerading As a Planet”

A star’s light is made up of a whole spectrum of colors, including some with wavelengths too short or too long for human eyes to see. If 40 Eridani A really were hula-hooping in time with a planet like Vulcan, all of those colors would shift toward red or blue at the same time, and by the same amount. But when Burrows and her colleagues used an instrument called a spectrometer to split the star’s light into all of its individual wavelengths, they realized that wasn’t the case for 40 Eridani A.

The star emits different wavelengths of light from different layers of its photosphere (the outer layer of a star that light actually comes from). And each of those layers seemed to be shifting differently than the others. In other words, the whole star isn’t wobbling, but something is happening inside it, just beneath the surface.

According to Burrows and her colleagues, the most likely culprit is a patch of sunspots: cooler, darker patches on the star’s surface, surrounded by hotter, brighter areas called plages. As those bright and dark patches rotate in and out of view every 42 days, they create the illusion of a star wobbling slightly as a planet circles it. As Burrows put it in a recent statement, Vulcan was “messy stellar jitters masquerading as a planet” all along.

This isn’t the first time a planet has turned out to be an illusion; in 2014, two planets orbiting a star 20 light years away — Gliese 581d and Gliese 581g — turned out not to exist, either.