Only when you take the dust jacket off this book is it revealed – printed around the hardback itself. The most famous photograph by Australia’s most famous photographer, the most iconic Australian image of the last century – Sunbaker, c. 1938.

Max Dupain once ruefully joked that his idea of hell was to be condemned to print the negative for eternity, but as his biographer, Helen Ennis, notes, he nonetheless kept on printing it. And it is still being printed and sold today.

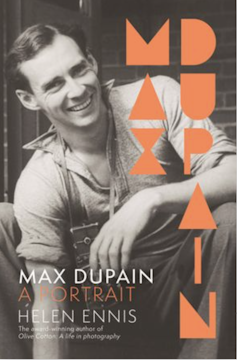

Review: Max Dupain: A Portrait – Helen Ennis (Fourth Estate)

Still, this book is not about icons, or fame or national identity. It’s about the dreams, loves, desires, doubts, angers, fears, and creative yearnings of an Australian man – not the “quintessential” or “typical” Australian man some may (mistakenly) take Sunbaker to represent, but a man whose fractured life, presented here through a series of beautifully nuanced readings of some his photographs, still tells us something relevant about Australia and Australian masculinity.

In this deeply thought book, Dupain’s photographs aren’t reproduced on gloss stock in their own section to “illustrate” a biographical argument.

Instead, they are printed within the pages of text. What is sacrificed in print quality is made up for by leading the reader chronologically through Dupain’s life and most of progressive Australian culture in the 20th century – modern literature, art, design and architecture, but also vitalist lifestyles (a social and aesthetic movement celebrating the “vital force” of the healthy human body) and pacifism.

Ennis writes responses of varying lengths, and from various angles, to the photographs. Not just the classics, but ones she’s found deep in the archive and among the unprinted but now scanned negatives in the State Library of New South Wales.

As various biographical, historical and personal issues are raised to be returned to and adumbrated later, her thoughts subtly accumulate into a complex portrait of a man and a rich picture of Australia.

Unknowables

As a biographer interested not in coherent biographical narratives but human and historical ambiguities, Ennis even lets us into her own thinking process as she confides her revisions to the reader.

Born in 1911 in Sydney, the energetic, aesthetic life Dupain craved was absorbed by proxy – from 78s of Beethoven on a portable gramophone, to reproductions of the old masters, the latest modern photography magazines from Europe, poetry books and, most significantly, the censored books of D.H. Lawrence extolling the vital life force. Early in his career, Dupain often planted significant books in his compositions – clues Ennis picks up on.

This reveals the importance of other spaces sometime overlooked in thinking about Australia. Not just the Aussie beach which, she finds, Dupain didn’t photograph all that much anyway, but other key spaces for people of Dupain’s ilk.

Places such as photography studios and darkrooms; as well as bookshops, like Bond Street Book Store, which he photographed with all the glowing allure of a Berlin cabaret one night in 1935.

After his death in 1992, Dupain’s library was dispersed in a precipitous suburban auction, but it was later partially reconstituted by the gallerist Josef Lebovic. This is just one of the many sources Ennis teases out to great effect. There are also diaries, interviews and reminiscences, and her own reactions to them, all of which she threads around each image.

Dupain always sought to keep his life divided into separate compartments: his home life, his work life, and his inner life. He divided his week into the working week, where he did commercial photography, and the weekend where he did much of his artistic “exhibition” photography.

And he attempted to divide his career into successive periods, such as the frivolous fashion photography of the 1930s he “left behind” for the essential simplicity of his post-war architectural photography.

Ennis overcomes this compartmentalisation in various ways. She homes in on the “undefinitive”, life’s glitches that lesser biographers would smooth over. She likes historical puzzles, and these ultimate unknowables about people and the past drive the reader’s investment in the book.

Why, for instance, did Dupain put an image of a rooster, titled Cock at the very end of his first monograph in 1948? Perhaps it had something to do with a book by D. H. Lawrence. Why, of the two vintage prints in existence of photographer Olive Cotton’s sexy Max after Surfing, 1937, is one personally inscribed to Dupain not by Cotton, but by the international fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huene?

A sexual energy

Another way Ennis overcomes Dupain’s self-compartmentalisation is to consider him in relationship to the women around him.

Not just his mother, not just his two wives, Olive Cotton and Diana Illingworth, but his models such as Jean Lorraine who contributed their own agency to his studio sessions, and his close studio associates such as Jill White. All endured but also created the “nightmare” Dupain sometimes became for them, as he assumed that everything and everyone would serve his “work”.

The arc of this book, like his career, springs out of his youthful work and his brief but significant engagement with nude photography in the late 1930s. Dupain’s photographic compositions, even of buildings or flowers, always had a sexual energy which drove through right to the end of his career.

His tumultuous World War II – with divorce, vividly diarised passionate love for Diana, and the death of his friend and employee the young cameraman Damien Parer – was also a watershed, as it was for the nation. During the war he felt acutely alienated from traditional ideas of Australian manhood, but in the same period made some of his tenderest compositions of sleeping men.

Ennis’s patient accumulation of short texts covering the subsequent decades, including the 1980s, when as a critic he became part of the resurgence in art photography, powerfully cohere around Dupain’s final passage to death in 1992. She even carries the ramifications through to today, when he still reverberates.

Career highlights

Sunbaker was nowhere near Dupain’s favourite photograph. Ennis discusses what he identified as a career highlight: Mother and Child, 1952, a portrait of his second wife and first child, Danina, dozing together in a spiralled cocoon.

With characteristic depth, she dissolves the barriers Dupain himself set up between the different parts of his life and reveals the pair were recovering from a restless night when this photo was taken because the child was teething at the time.

Dupain thought his very best photograph was Meat Queue, 1946. Made not on a beach but in a butcher’s shop, for Dupain it signalled his post-war turn to documentary realism.

He has caught one figure suddenly breaking out of the line of stolid Australians queueing for their meat rations. It’s a “decisive moment”, but it’s also a classic Dupain compositional trope – energising the drama but not creating disorder.

This revelatory book is a portrait of a man who thought he was different to the rest of us but was then troubled by the self-doubt that perhaps he wasn’t after all.

It’s a portrait of man driven to elevate himself through so much hard creative work that it destroyed the other parts of his life that made him what he was in the first place – some of his relationships, some of his openness, some of his optimism.

It’s a portrait of a man who decided to turn inwards to an idea of Australia for creative sustenance, but then found it could never be enough.

But it’s also about the existence of other types of Australian masculinity, and other types of Australia, types which had been subsumed, ironically, by the likes of Sunbaker. An understanding of these kinds of masculinity is more relevant now than ever.

Myself and the author of this book were both colleagues at the ANU School of Art and Design, and we see each other occasionally as colleagues.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.