Texas is number one!…on many worst-of lists when it comes to public health. Over the past decade, there’s been upheaval in health care here and nationwide. In Texas, uninsured rates dropped a bit, then rose again. Access to reproductive health care has shrunk. Medical services in rural areas have disappeared. Vaccine exemptions for kids have skyrocketed. I broke down how access to health care has fundamentally changed in Texas over the past 10 years.

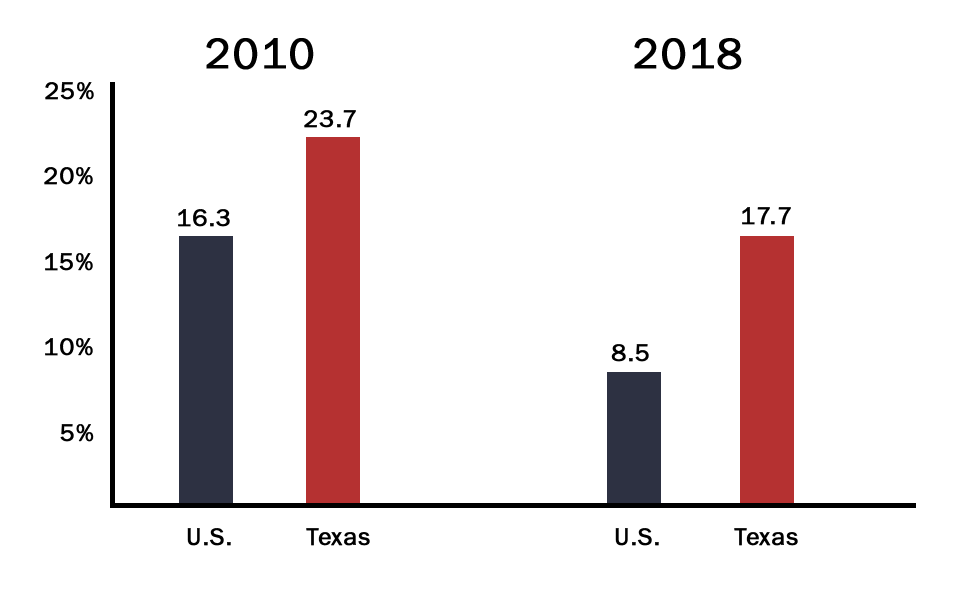

Uninsured rate

As I mentioned, Texas holds many unwanted first place rankings when it comes to public health, but the uninsured rate is perhaps the most pernicious designation. For years, the state has consistently had the highest uninsured rate in the country, which is now more than double the U.S. rate. And it’s getting worse: In 2018, the uninsured rate increased for the second year in a row, after several years of steady decline following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, thanks in large part to Republicans’ efforts to sabotage the law and cut enrollment assistance.

Texas is one of 14 states that continues to reject the chance to significantly reduce its number of uninsured residents by declining billions in federal funding for Medicaid expansion under the ACA. Instead of covering an additional 1.4 million uninsured adults, the state is leading a lawsuit backed by the Trump administration to dismantle the ACA entirely. If successful, the effort will kick millions of Americans off their health insurance, eliminate pre-existing condition protections, and much more. On December 18, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the individual mandate unconstitutional (Congress had already eliminated the associated penalty), but punted the bigger question of whether the rest of the law falls with it back to a district court.

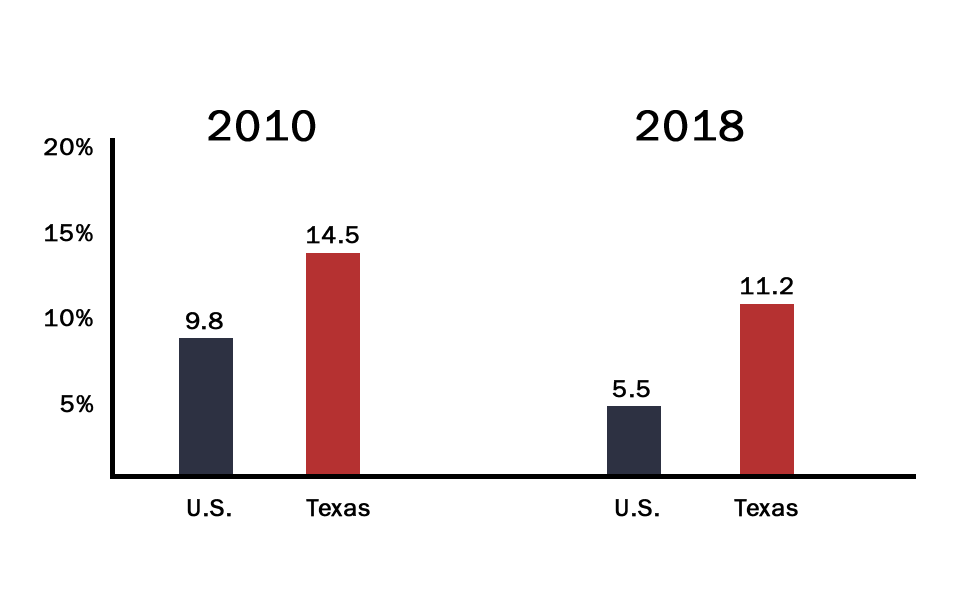

Uninsured rate for kids

Don’t be fooled by the seeming improvement over the past decade. Although the ACA managed to bring Texas’ rates of uninsured children down, roadblocks and refusals from Republicans thwarted progress seen in other states. Mirroring the adult population, Texas now has the highest uninsured rate for children—double the national rate—and is home to more than one-fifth of all uninsured kids in the country. In 2018, there were 873,000 uninsured kids in Texas, up from 752,000 in 2016, according to a report from Georgetown University (it also found that these numbers are rising nationally). Researchers attribute this to the Trump administration’s attacks on the ACA and cuts to enrollment outreach, and his anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric, as well as Texas’ burdensome paperwork requirements that kick thousands of eligible kids off Medicaid each month.

Number of non-medical vaccine exemptions for kids

Since they were first green-lit by the Texas Legislature in 2003, the number of non-medical “conscience” exemptions from mandated vaccines for kids increased from 2,300 to 64,176 in the 2018-2019 school year, according to data from the state health department. Texas—home to notorious anti-vaxxer Andrew Wakefield, who claimed a now-debunked link between vaccines and autism—has become a “hotspot” for vaccine exemptions, scientists warn, thanks in large part to a growing anti-vaccine movement.

Medical experts have sounded the alarm about the potentially fatal consequences if lawmakers don’t act fast to close the vaccine exemption loophole. This year, Texas had 21 confirmed measles cases, the most by far since 2013. All the while, some state lawmakers this session sought to make it even easier to opt out of vaccinations.

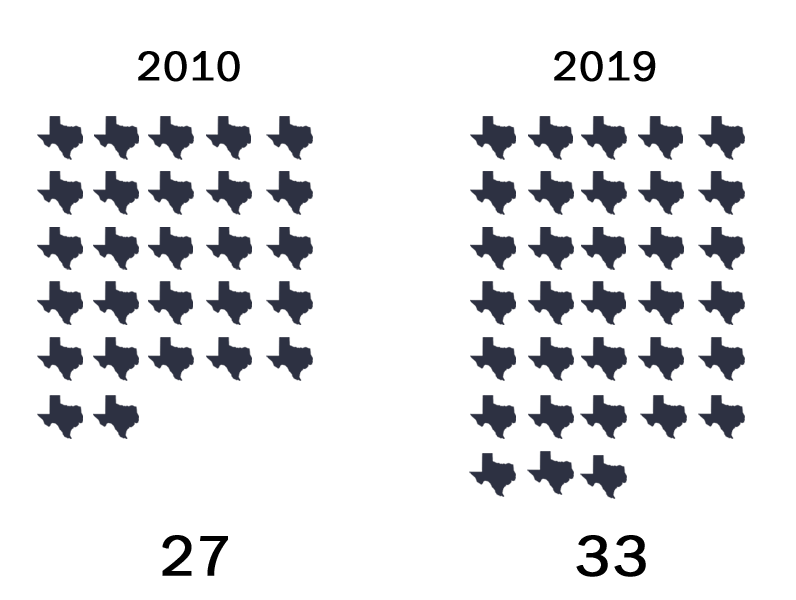

Number of rural hospitals

Rural health care is in crisis across the country, but it’s felt most acutely in Texas. The Lone Star State leads the U.S. in rural hospital closures with more than 20 over the past decade. Many more are at a high risk of closure, according to the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals. Today, there are just over half the number of small town hospitals as there were in the 1960s. Many of those that have stayed open have cut critical services, like maternity care, to make ends meet. Fewer than half of the remaining 158 rural hospitals in Texas still deliver babies.

And state lawmakers have refused to make the most straightforward change that advocates and medical professionals say would help stanch the bleeding: expand Medicaid.

Number of counties without a doctor

This year, about one-fifth of Texas’ 254 counties have just one doctor or none at all, according to data from the state health department. In the past two decades, the number of counties with zero doctors has more than doubled as experts continue to sound the alarm. But as small town doctors retire or die, few medical school graduates are settling in rural towns to replace them. The gaps can leave residents traveling hundreds of miles for even basic care. Statewide, the shortage of primary care physicians is expected to grow from about 2,000 to nearly 3,400 in the next 10 years.

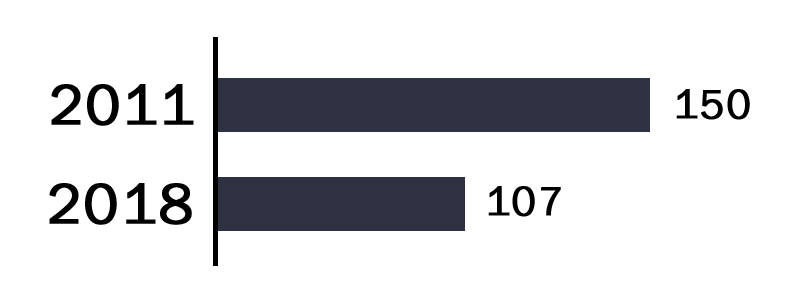

Number of abortion clinics

About half of Texas’ abortion clinics shuttered following the passage of sweeping anti-abortion legislation in 2013. Major provisions of the law were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016, but even now few have reopened. The clinics that remain are clustered in urban areas, leaving vast swaths of West and South Texas without a provider, and forcing some patients to travel as far as 300 miles one-way to terminate a pregnancy.

Since the Supreme Court decision, Texas Republicans have continued passing anti-abortion laws that have been temporarily blocked in court, including one that requires the burial or cremation of fetal remains following abortions and miscarriages, and another that bans the most common form of second trimester abortion.

Meanwhile, the state legislature has funneled more and more money into crisis pregnancy centers—faith-based clinics that don’t provide reproductive health services like gynecological exams, birth control, cancer screenings, and STD testing. Funding for the state’s Alternatives to Abortion program has ballooned since its inception in 2006. In the 2010-11 biennium, lawmakers budgeted $8 million toward the program; for 2020 and 2021 that number has grown to nearly $60 million, with another $20 million available if needed. A fraction of the funding each year has come out of Texas’ Temporary Assistance for Needy Families—the federal cash assistance program for poor families.

Texas women served by the state’s health programs

In 2011, state lawmakers slashed the family planning budget by two-thirds. Two years later, they kicked Planned Parenthood and other abortion “affiliates” out of the state women’s health program, leaving millions in federal funding on the table and creating a new state-run program instead. More than 80 family planning clinics closed, and tens of thousands of Texans lost access to reproductive health care.

The most valuable comparison to make from 2010 to 2019 would be the number of patients served by the women’s health program. But state officials changed their counting methodology in 2016, making it impossible to draw an apples to apples comparison. Health commission staff and lawmakers have pointed to the number of providers in the state’s replacement program, Healthy Texas Women, as a metric of its success. But this has little to do with whether the state has actually filled the gap in services left by Planned Parenthood, which previously served 40 percent of patients in the state’s women’s health program. In fiscal year 2017, almost half of the 5,400 or so providers in Healthy Texas Women didn’t see a single patient in the program, and state data shows that the average number of patients per provider is still far below that in 2011, indicating that larger providers have generally been replaced by smaller clinics and individual doctors who see fewer patients.

Thanks to significant investment in Healthy Texas Women and recent auto-enrollment requirements, the number of patients served has increased substantially in the years since 2016—when the new counting methodology was implemented—after years of decline. But the percentage of patients enrolled who are actually accessing services is still far below the rate in 2010, according to the left-leaning Center for Public Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile, the state last year pulled its contracts with the program’s most high profile and controversial provider. The Heidi Group, the anti-abortion organization awarded multi-million dollar state contracts to serve more patients in its first year than Planned Parenhood had, ended up serving just a fraction of the people promised and misused millions in taxpayer funding. After I published an investigation in June that found contract violations and lack of oversight by the group, state investigators last month released a report echoing those findings, ordering it to repay nearly $1.6 million and calling for an expanded investigation.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Who Is John Cornyn Serving? The senior senator from Texas has mastered the art of political subservience, making him very powerful—and perhaps vulnerable.

-

Critical Condition: Rural health care is in crisis around the country, but Texas is suffering the most. At least 20 small-town hospitals have closed since 2013.

-

The Ghosts of Jefferson: This East Texas tourist town calls itself “the most haunted town in Texas,” but its whitewashed ghost stories elide a complex racial history.