Mark and Carol Brault, who own 114 acres of forested land in Hartland, Connecticut, operate a private nature preserve that charges admission to visitors interested in seeing bears and other wildlife. In a 2020 lawsuit, the town of Hartland accused Mark Brault of violating a local ordinance against feeding bears, a charge that he denies. The latest wrinkle in that ongoing dispute involves the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), which the Braults say has defied the Fourth Amendment by attaching a camera to a black bear that is known to frequent their property.

"Turning wildlife into unguided surveillance drones is unbearable," Institute for Justice (I.J.) senior attorney Robert Frommer, a Fourth Amendment specialist who is not involved in this case, writes in an email. "Connecticut should paws its animal camera program so as not to infringe on Nutmeggers' privacy and security."

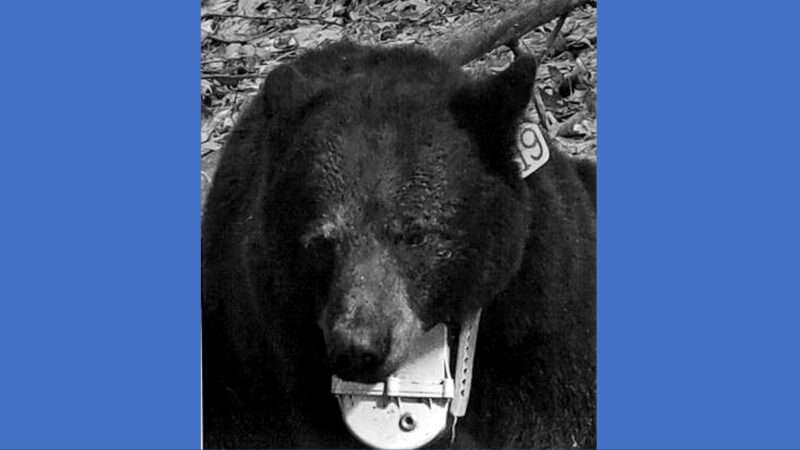

DEEP's bear-borne camera is a twist on longstanding warrantless surveillance of private property by wildlife agents, which I.J. has challenged as a violation of state constitutional protections in Pennsylvania and Tennessee. In a complaint that the Braults filed last week in the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut, they argue that DEEP's deployment of an ursine spy, identified by a state tag as Bear Number 119, violates the Fourth Amendment's ban on unreasonable searches.

The Braults are seeking an injunction ordering DEEP to "remove and disable the cameras from all tagged bears within ten miles of the plaintiffs' residence, to destroy all photographic evidence gathered by the aforesaid surveillance, and to cease and desist from conducting such warrantless surveillance in the future." But for reasons that Reason's Joe Lancaster explained last year, their claim looks iffy under the U.S. Supreme Court's "open fields" doctrine.

Sometime between January 1 and May 20, according to the Braults' complaint, DEEP "affixed a collar to Bear Number 119 which contained a camera." On May 20, "Bear Number 119 approached to within 200 yards of the plaintiffs' residence, which is located near the center of their property." The bear "was wearing the aforesaid camera at the time and, upon information and belief, that camera was activated and taking and transmitting pictures or video of the interior of the plaintiffs' property to the defendant."

Mark Brault "noticed that the bear now had not just an ear tag but a collar, and so he got on his camera and zoomed in on the bear, and not only did it have a collar, but the collar had a camera on it," John R. Williams, Brault's attorney, told CT Insider. "That's a bear that the DEEP knows is a frequenter of the property. So what does that say to me? That says to me that they're engaging in a warrantless search of his property."

The Braults say DEEP "did not have a search warrant authorizing or permitting photographic surveillance of the interior of the property of the plaintiffs." Presumably the bear did not have a search warrant either.

In an accompanying affidavit, Mark Brault notes that the property is "clearly posted with 'no trespassing' signs." But according to the Supreme Court, the fact that the Braults own the property and had posted signs to that effect does not matter under the Fourth Amendment.

"The special protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their 'persons, houses, papers and effects,' is not extended to the open fields," Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote for the Court in the 1924 case Hester v. United States, which involved illegal whiskey production. "The distinction between the latter and the house is as old as the common law."

The Court reaffirmed that principle in the 1984 case Oliver v. United States, which involved a marijuana farm discovered by Kentucky state police. "In the case of open fields, the general rights of property protected by the common law of trespass have little or no relevance to the applicability of the Fourth Amendment," Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. wrote in the majority opinion. Although the marijuana growers "erected fences and 'No Trespassing' signs around the property," the Court rejected "the suggestion that steps taken to protect privacy establish that expectations of privacy in an open field are legitimate."

The implication was that "open fields" need not actually be open. Even when private property is fenced and marked with "No Trespassing" signs, the Court said, "no expectation of privacy legitimately attaches to open fields." At the same time, it acknowledged that the Fourth Amendment does apply to the area "immediately adjacent to the home," known as the "curtilage."

That distinction could provide an opening for the Braults, since they say the camera-carrying bear "approached to within 200 yards" of their home. The bear, unschooled in the fine points of Fourth Amendment case law, might well meander onto a portion of the property that courts would recognize as curtilage.

In that respect, the camera carried by Bear Number 119 is different from the fixed cameras that wildlife agents have posted on private property in states such as Pennsylvania and Tennessee. If the bear has entered or might enter the curtilage around the Braults' home, that could be constitutionally significant even under current precedents.

I.J. argues that the open fields doctrine is misbegotten. It says the "distinction" that Justice Holmes deemed "as old as the common law" in Hester was based on a misunderstanding.

"The sole citation to support this historical assertion was to three pages of Blackstone's Commentaries," Frommer and fellow I.J. attorney Anthony Sanders noted in a 2017 Supreme Court brief. "The problem with Justice Holmes' citation is that in those pages, Blackstone was not talking about open fields, officers of the law, or even trespass. Instead, he was discussing the elements of burglary. Blackstone simply lays out the rule that to commit burglary, among other elements, the burglar must break into a home, and do it at night."

The Supreme Court "took this distinction between burglary and other crimes and gave it constitutional significance by applying it to an area—an open field—that

Blackstone does not even address," Frommer and Sanders added. "By the same, ill-founded reasoning, Hester could have stated that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to the government entering homes during the day, or entering buildings such as barns and warehouses at all, all areas Blackstone contrasted to a break-in of the home at night….That is the logical conclusion once the citation to Blackstone is actually examined. In short, the citation to Blackstone did nothing to support the Court's refusal to apply the Fourth Amendment to an 'open field.'"

But given the persistence of this mistaken doctrine, Frommer says, "there likely isn't a viable Fourth Amendment claim" against DEEP's use of bear-borne cameras. And although "Connecticut's constitution protects 'possessions,' which we believe includes private land," he says, the Connecticut Supreme Court "recently rejected a challenge to the open fields doctrine under the state constitution."

Frommer thinks the best bet for a Fourth Amendment claim in this case would emphasize the unpredictable paths of camera-carrying bears. "The problem with slapping a camera onto a bear and then unleashing it into the wild is that you can't control where that bear goes," he writes. "For all the officer knows, the bear could park itself right outside somebody's house, with the camera capturing everything therein."

As Frommer sees it, "What officials did here should count as a 'search' upon a straightforward understanding of the term, which is just a purposeful investigative act. And this tactic seems unreasonable given the potential breadth of what the camera would expose, not just as to the couple, but for other people and homes it may come across. I don't know if that's a winning argument, but it's what I would contend if I were in their shoes."

The post A Connecticut Couple Challenges Warrantless Surveillance of Their Property by Camera-Carrying Bears appeared first on Reason.com.