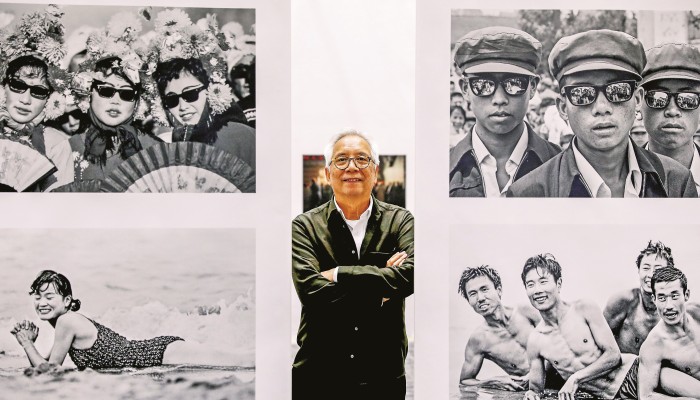

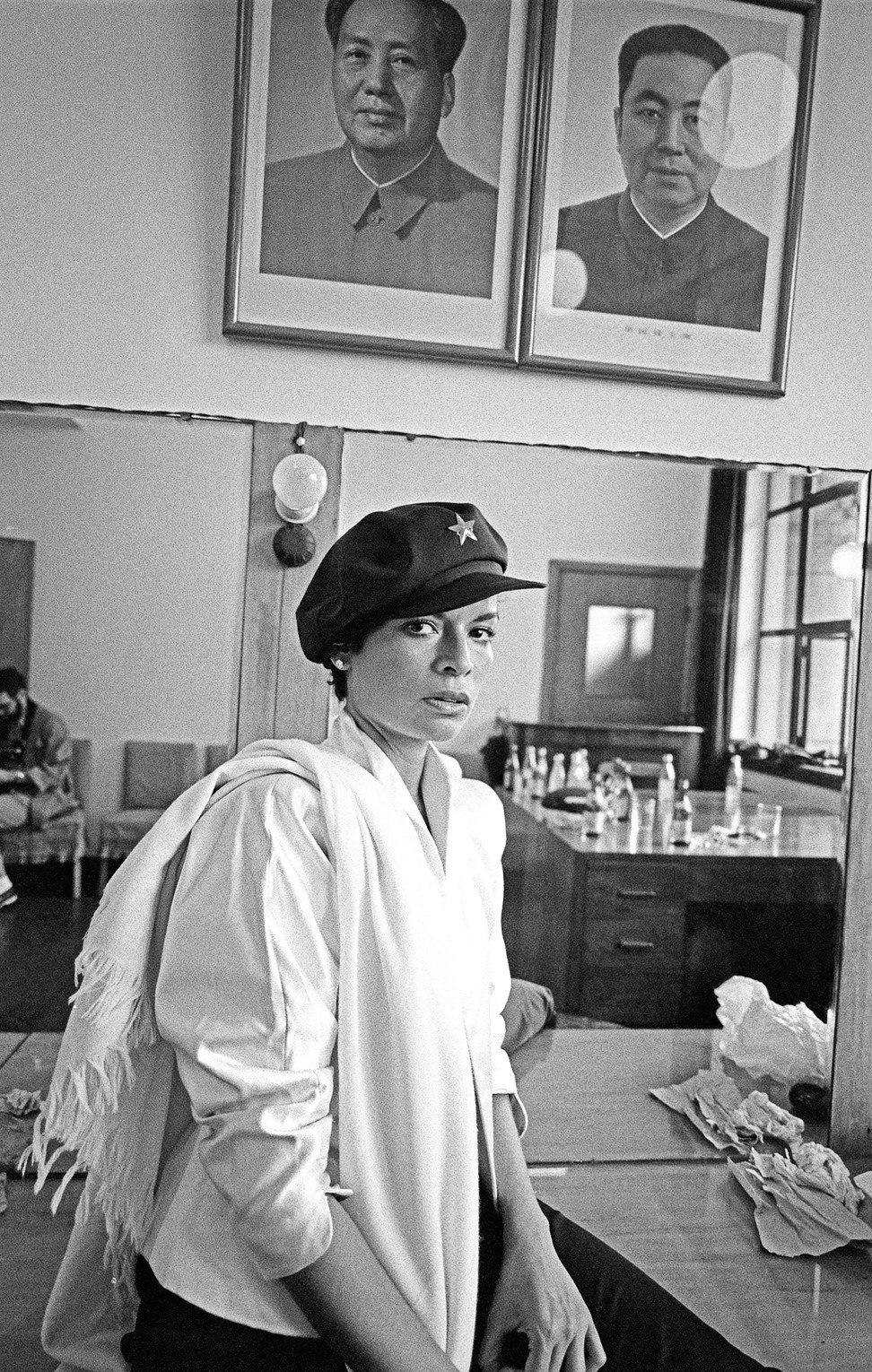

As a photojournalist who covered China for over 40 years, Liu Heung Shing has unique insights into how its people think, and the way foreigners perceive the country. His powerful pictures challenge stereotypes and get below its surface.

From young Chinese couples disco dancing, to a man outside Beijing’s Forbidden City holding out a Coca-Cola bottle after the drink was reintroduced to the market in 1981, the poignancy is there for all to see.

Liu, who was born in 1951 in the then British colony of Hong Kong but spent his early years living in mainland China with his mother, worked as a news photographer for several Western media organisations, including Time, Life and the Associated Press news agency.

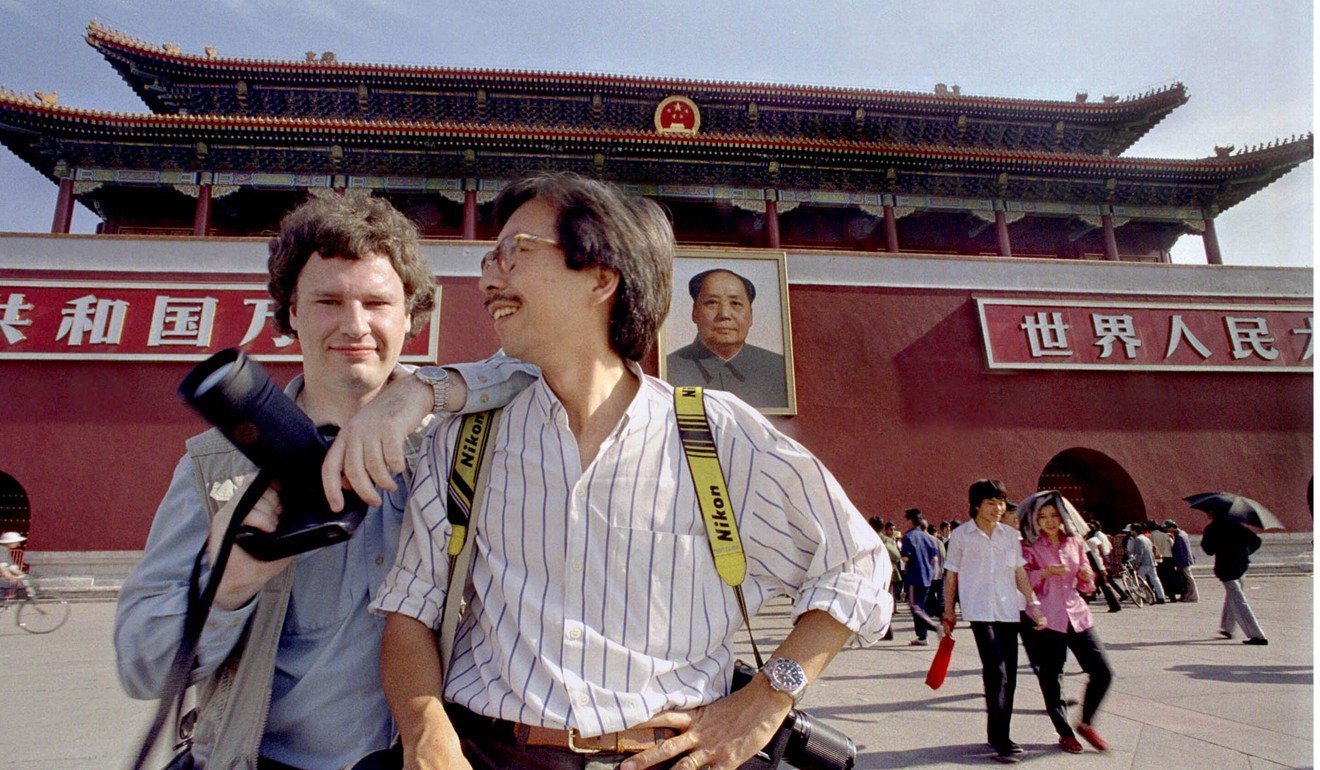

His coverage of the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy student protests in 1989 included images of the violent June 4 crackdown but also, before that, rock bands playing, the Democracy Wall where citizens put up big-character posters protesting about political and social issues, and exhausted protesters asleep among a sea of banners.

“I was there mid-May until the 9th of June, when things became impossible and all hell had broken loose,” he says. “Looking back at everything I had been doing over 40 years, it’s only now that I had the time and leisure to go through all the negatives,” he says, at his Shanghai home in the former French Concession.

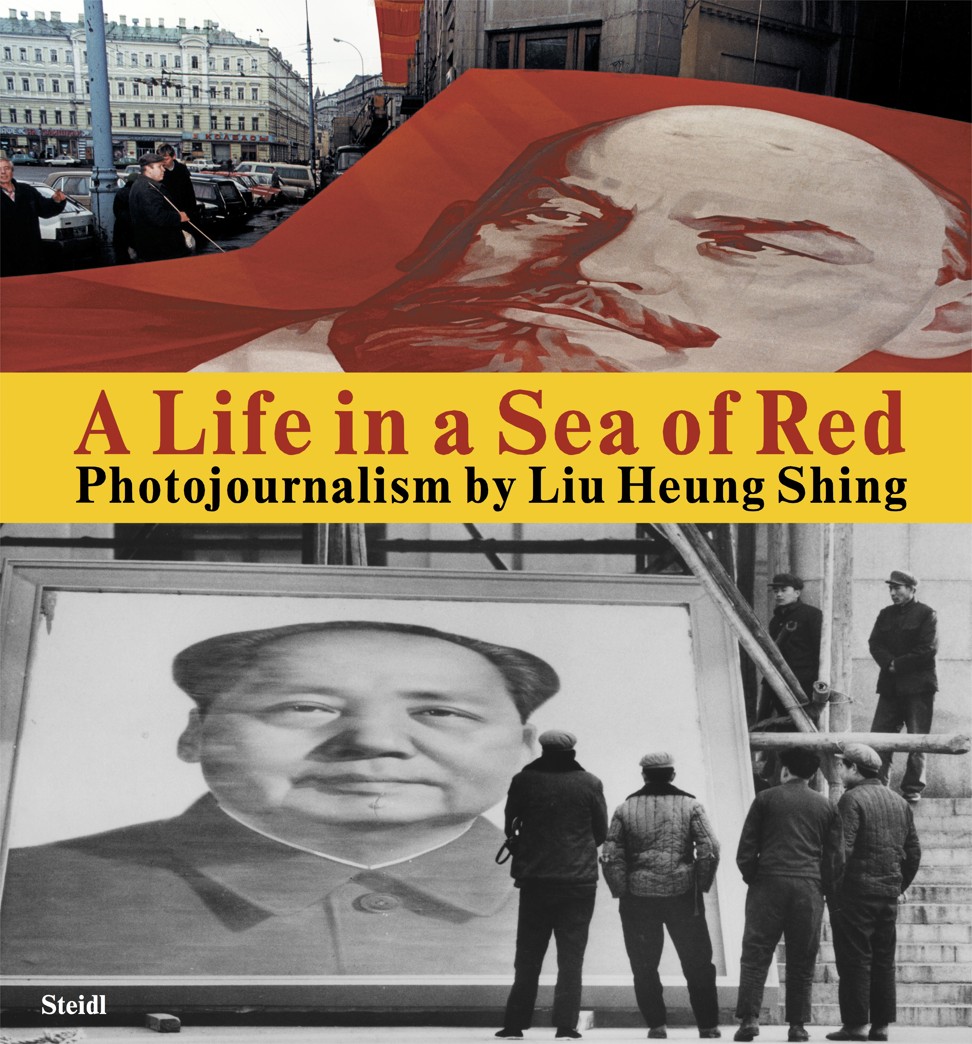

Liu, now 68, is referring to the images in A Life in a Sea of Red, a book of his award-winning work from China and Russia, published by Steidl and to be launched in Hong Kong during Art Basel this month. The title is a take on a Chinese proverb about perseverance in tumultuous times: Ku hai yu sheng, or “Alive in the bitter sea”.

“These two bodies of work [from China and Russia] will still find relevance today. It also has something to do with how I see these two countries, where I find interest,” says Liu. “I would photograph historical moments but still focus my lens on the daily lives of the people, which is much more enduring.”

There are moments of humour, fear and furious dissent, as well as tenderness and love in his images. “In the case of China, it was over four decades,” Liu says. “In the case of the Soviet Union, it was for four years at the pivotal moment when they collapsed, and after that all the former states becoming independent.”

Liu, who attended kindergarten and three years of primary school in China before returning to Hong Kong, moved back to China after the death in 1976 of Mao Zedong, sensing that big shifts were about to happen. He documented events such as “Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping opening the door for full diplomatic normalisation in 1979 … a long interlude after 1972, when Richard Nixon broke the ice”, the events of 1989 and China’s economic boom.

If you do not understand the first 30 years of China under Mao, Liu argues, “you do not understand the next 30 years of development and why it was so fast. Mao made colossal mistakes by introducing the Great Leap Forward … almost 30 million people were wiped out. It was one of the world’s greatest man-made famines.”

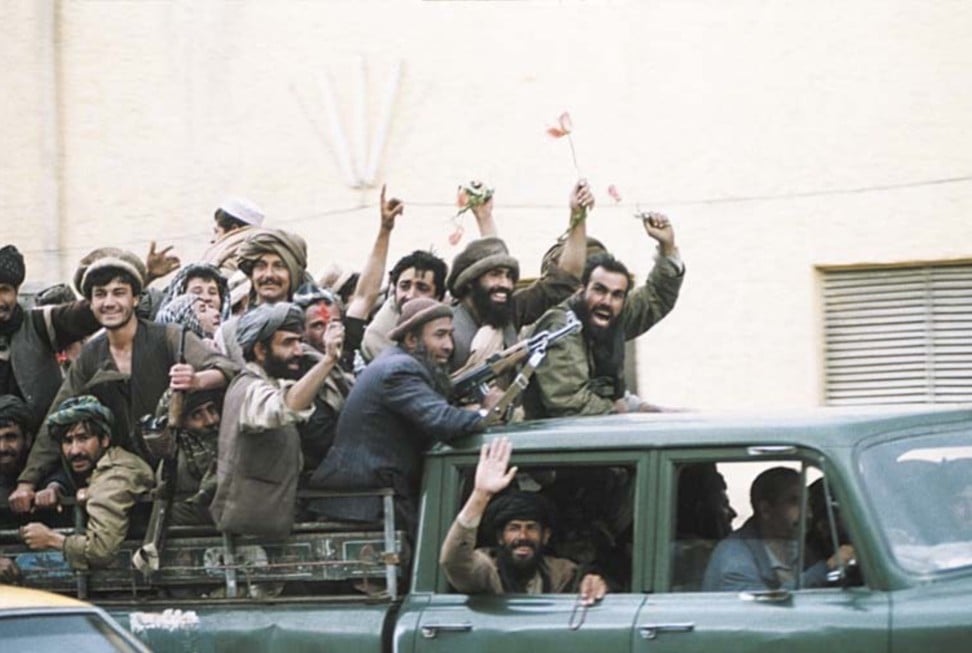

What is most striking about the images in A Life in a Sea of Red are their depiction of hope amid the hardships of communist rule. Liu photographed Soviet troops pulling out of Afghanistan and the mujahideen subsequently storming Kabul’s former presidential palace, the “St Petersburg” sign replacing “Leningrad” after the end of Soviet rule, a strike by coal miners in Ukraine, and young Russian women posing playfully for the camera.

The raw emotion of housewives in front of the Kremlin in Moscow in 1990 accusing the Communist Party of corruption is undeniable. Scenes at KGB headquarters, with jubilant Boris Yeltsin supporters celebrating a landslide victory, contrast with images of empty shelves in a state-owned Moscow supermarket in 1991.

“This is a story, an evolution of how it collapsed. I’m not just chasing images of the press conferences with the leaders. It’s about something going extremely wrong and finally collapsing,” Liu says.

One of his most enduring images of Russia captures the moment when president Mikhail Gorbachev puts down his resignation speech that marked the end of the Soviet Union, and of the cold war, after delivering it on December 25, 1991. The papers blurred, and Gorbachev looking defeated, it was part of a series for Associated Press that won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

“I decided to focus on the moment when, at the end of his speech, he signed his resignation paper. I had to use a slow shutter speed of 1/30 second,” Liu explains. “Only this would show the motion of the paper as he laid it down on the table in front of him and, in so doing, laid to rest the USSR. I had one chance to get the shot – it was a calculated technical risk. The slow shutter speed could just have easily resulted in an entirely blurred picture.”

As one of the few photographers to have extensively documented two of the world’s major communist powers, Liu developed deep insights into how political dogma affects people’s day-to-day lives. He came from landowning stock, a class of people who were persecuted in China in the late 1940s and 1950s – around the time he was born.

“That was the first lesson I learned about politics and what politics can do to people,” he says. “If you came from parents of workers, farmers and army soldiers, then you have a better chance than anyone to go somewhere.”

His early childhood in China endowed him with some knowledge about communism and “how it creates inequality and absurdity according to the new norm”.

One of the most poignant images Liu shot in China was taken in 1981 and captures students peacefully studying under the street lights by Tiananmen Square. So familiar are images of the square from the 1989 protests and crackdown that it takes a moment to register that there is nothing sinister here – just stillness.

China has since recast communism in a “socialist-capitalist” mould. Liu has been there with his camera to witness the economic boom, the shift from collectivism to individualism, and the rise of consumerism, fashion, art and personal expression.

Does the fact that Liu is a Chinese photojournalist who has lived in the US, Russia, Hong Kong, South Korea and France – but ended up documenting China – inform his work and offer something different from his Western peers?

“For any photographer, you can’t not have your own world view and cultural view, and therefore your own interpretation. In China, for many years, most of the [famous] photography was done by the likes of Margaret Bourke-White or Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose view was very French, in a sense,” he says.

“In the 1950s United States, the Americans would have never looked at their country the way that Robert Frank or all these European photographers did. So to answer your question, it means an awful lot. It’s less discussed because the photography world is dominated by Americans and Europeans.”

Photojournalism has changed a lot since Liu stepped back from active duty. There’s been the digital revolution, but also community reportage, 24-hour news cycles, the growth of the internet and the spread of “fake news”.

Back then, photos like Liu’s – printed in newspapers and magazines – were often the only window on a country or culture for mass public consumption.

But Liu is not a creature of nostalgia, nor does he pine for the old days. He is pushing forward the dialogue about photography through the Shanghai Centre of Photography, which he founded in 2015. At the centre, he highlights the work of younger talent as well as established giants, both local and foreign.

Today, stories about China, the US and Russia (“with an economic output smaller than Guangdong” province, he notes) still dominate the world news cycle. A Life in a Sea of Red is a reminder of how history still informs and lends context to the present.

“With this book, I want to find a way to mix these two self-evidently quite important stories,” says Liu. “These are very relevant stories. They might be stories about the last quarter of the 20th century, but can very much still dominate the stories of the 21st.”

Liu’s work will be exhibited at two Art Basel Hong Kong shows, by Beijing’s Star Gallery, and Chancery Lane Gallery, in Central, Hong Kong. A Life in a Sea of Red will be launched during Art Basel at Kerry & Walsh and Bookazine stores across Hong Kong