The Australian Labor Party is Australia’s oldest political party, and Anthony Albanese is its 13th prime minister.

He would do well to recall the experiences of his predecessors.

Incoming Labor prime ministers have invariably faced immediate and serious economic challenges, some of them bequeathed by conservative governments that styled themselves as superior economic managers.

In October 1929, Labor leader James Scullin defeated the conservative Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 12 days before Wall Street began the great crash that set off the Great Depression.

The reverberations put the skids under the new government.

Even its brightest star, mercurial treasurer Edward Theodore, could not save it from annihilation two years later as the grip of the depression tightened.

It didn’t help that the prices of Australia’s major export commodities, wool and wheat, were in free-fall while the Commonwealth and the states owed millions in foreign loans and servicing costs to London.

Bruce wouldn’t have been the only politician – before or since – to have thought privately that the election he won was a good one to lose.

Labor often inherits problems

The Albanese government faces economic challenges of its own.

When the Reserve Bank board meets on Tuesday June 7, it is likely that interest rates will climb yet again. It will be part of a reckoning neither side faced up to squarely during the campaign.

Like Scullin and Theodore in 1929, Albanese and his treasurer Jim Chalmers have inherited a mountain of public debt and a stubborn budget deficit.

In Scullin’s time the Commonwealth and states had borrowed heavily for projects such as railways. The debt was mostly owed to British banks, and had to be honoured.

À lire aussi : The good old days: how nostalgia clouds our view of political crises

At least for the moment Albanese will enjoy high commodity prices.

But what if overseas credit agencies decide to send a message about what they believe to be overspending? They have done it before during the 1980s, removing Australia’s AAA credit rating under (Labor) Prime Minister Bob Hawke, restoring it under (Coalition) Prime Minister John Howard.

It would fit in with the widely-held belief (even in financial markets) that Labor governments are spendthrift, and push up the cost of borrowing.

Labor is often told it can’t manage money

It is here we see the great asymmetry in Australian politics at play. Labor governments are perceived to be poor economic managers, regardless of what circumstances require them to do, compared to Coalition governments who are supposedly superior, regardless of what circumstances require them to do.

Scott Morrison put this way during the campaign: “Labor can’t manage money”.

The sentiment has plagued Labor since Scullin’s day.

The Whitlam Labor government had the misfortune to come to power just as the long post-war boom was about to end. Within a year, a 1973 oil price hike by members of the Middle East oil producing cartel supercharged inflation and unemployment, derailing the Labor’s planned spending on social programs and solidifying the perception that it couldn’t manage money.

Labor has a history of managing well

But the necessary cutbacks in spending began with Labor itself, in Treasurer Bill Hayden’s contractionary August 1975 budget, implemented months later by the Fraser Coalition government after it took office in November 1975.

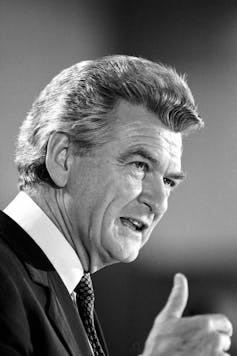

In March 1983, the Hawke Labor government took power only to be informed by Treasury Secretary John Stone that the budget deficit was far greater than the figure which departing Coalition treasurer John Howard had claimed.

Treasurer Paul Keating faced the need to restrain expenditure to relieve pressure on borrowing and on interest and exchange rates.

A fall in Australia’s terms of trade in early 1985 made the need for deep budget cuts more urgent.

The Hawke cut government spending as a proportion of gross domestic product while putting in place a prices and incomes accord, which successfully moderated pay rises in return for Medicare and superannuation.

Months after being elected in late 2007, the Rudd Labor government was warned of a looming financial crisis in the United States. It held off on its plans to slash government spending and developed a stimulus package that prevented mass unemployment, avoided recession, and kept Australia’s financial institutions alive.

The Coalition is treated more gently as economic managers

This success didn’t deter the Coalition from demonising the borrowing required to fund the package, even though Labor left office with net debt of 10% of GDP, compared to the 31% of GDP forecast in the Coalition’s 2022 budget.

À lire aussi : A new dawn over stormy seas: how Labor should manage the economy

Like Scullin in 1929, Albanese has been bequeathed a formidable list of problems. They include rising interest rates, stagnating wages and soaring inflation.

He also has to attend to a stubborn budget deficit while fulfilling his promises of increased funding for childcare, education, housing and aged care.

As has become the norm in Australia, these challenges have been made harder by the different ways in which the Coalition and Labor are judged.

Correction. An earlier version of this piece said Anthony Albanese was Australia’s seventh Labor prime minister. It has been corrected to say he is Australia’s 13th Labor prime minister. The author apologises for the error.

Alex Millmow ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.