For the first time in 20 years, the NBA began its season with no Black-owned franchises.

In fact, there’s been only one Black majority-owned team in league history.

In late 2002, the NBA awarded an expansion team, the Charlotte Bobcats, to Black Entertainment Television co-founder Bob Johnson. Four years later, former NBA star Michael Jordan bought a minority stake in the franchise, and in 2010, he bought Johnson’s stake. However, Jordan sold his majority stake in the franchise in July 2023.

This lack of diversity in basketball team ownership is especially disappointing considering the rich history of Black ownership in sports, which began when the top leagues in the U.S. were still segregated.

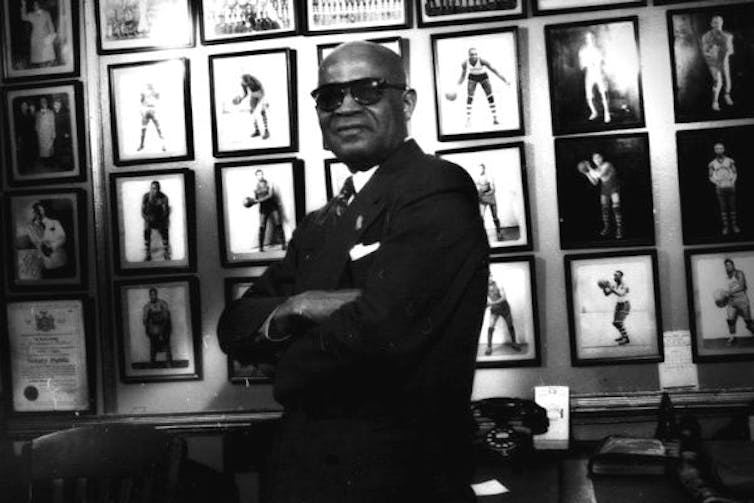

A century ago, one of the top pre-NBA professional franchises began play in Harlem thanks to the efforts of a Black business owner named Bob Douglas.

A challenge to the dominance of white sports

My students are often surprised that the history of professional team sports in the U.S. goes far beyond the NBA, NHL, NFL and MLB. But the media’s focus on the “big four” leagues can cause fans to overlook the incredible accomplishments and leadership of many pioneers in athletics, including those from marginalized groups whose participation in mainstream leagues were limited or banned.

The first 50 years of professional basketball was an amalgam of regional leagues and barnstorming teams. As with baseball and football, basketball teams from this era were segregated. But white teams and Black teams would square off against one another in exhibitions as they toured the country.

On the business side, many white businessmen were profiting from – if not exploiting – this Black talent pool, arranging tournaments and competitions and taking a disproportionate cut of the earnings. But Black entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to support Black communities through sports by keeping the talent – and money – from exclusively lining the pockets of white owners.

Douglas helped found the Spartan Field Club in 1908 to support his and other Black New Yorkers’ interest in playing sports. These clubs provided facilities and organized amateur teams across a number of sports, with cricket and basketball being among the most popular.

Douglas had fallen in love with basketball after first playing in 1905, only a few years after he had immigrated to New York from St. Kitts. Despite encountering discrimination as a Black man and immigrant, he founded and played for an adult amateur basketball team within the club named the Spartan Braves. He transitioned to managing the club in 1918.

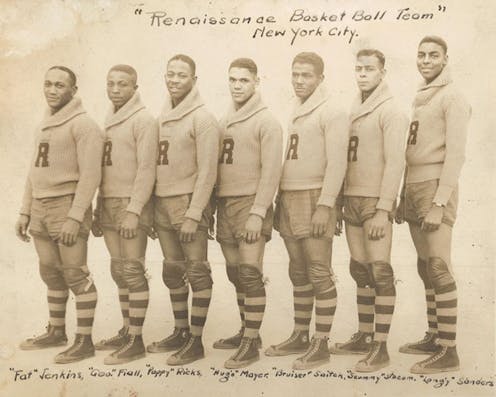

Douglas was searching for a permanent home for his team and offered to rename the Spartan Braves the Harlem Renaissance in exchange for the use of the Black-owned Renaissance Ballroom & Casino on Seventh Avenue between 137th and 138th streets. The team played its first game as the Renaissance on Nov. 3, 1923, with Douglas signing his players to full-season contracts.

Two years later, the “Rens,” as they came to be called, were declared the World Colored Basketball Champions. The squad went on to establish itself as a national powerhouse and competed in some of the first professional basketball games between white teams and Black teams. In 1925, the Rens bested the Original Celtics, a white team from Manhattan’s West Side that many viewed as the top team in the nation.

The next year, another all-Black team claiming Harlem as its home was founded. Unlike the Rens, however, the Harlem Globetrotters had no connection to the New York City neighborhood. They were based out of Illinois and had a white owner, Abe Saperstein, who sought to profit from the connection between Black Americans and the place that served as the epicenter of Black culture.

A stretch of dominance

During the 1932-33 season, the Rens won 120 of the 128 games they played, including 88 in a row. Six of the losses came at the hands of the Original Celtics, although the Rens did end up winning the season series, beating their all-white rivals eight times.

Basketball’s influence on Black culture continued to grow throughout the interwar period. During Duke Ellington concerts, basketball stars like Fats Jenkins would entertain the crowd between sets, facilitating the deep cultural connection between basketball and Black music that continues today.

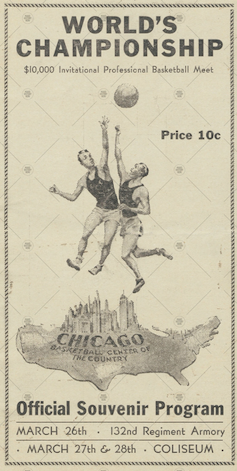

By the end of the 1930s, the Rens and Globetrotters were not just looking to prove themselves as the best Black teams but also establish themselves as the best basketball teams in the nation.

In 1936, the New York Rens played a two-game series against the formidable Oshkosh All-Stars, who played out of Wisconsin. The popularity of the games led to Douglas and Oshkosh founder Lon Darling to agree to a longer series, with the Rens winning three of the five games.

Douglas agreed to extend the competition another two games to create a “world series.” Oshkosh ended up winning them both to take the series. The victories led Darling and the All-Stars to join what would become the National Basketball League, a predecessor to the NBA. The NBL signed its first Black player in 1942, five years before Jackie Robinson made his MLB debut.

As the NBL grew in popularity, the World Professional Basketball Tournament was created. In the 10 years the tournament was played, NBL teams won all but three championships, with all-Black teams claiming the other three. But only one of those teams – the Rens – had a Black owner.

War, competition and integration

The Rens struggled to maintain their dominance after the newly established Washington Bears, another all-Black team, poached a number of Ren players in 1941. The Bears were founded by legendary Black broadcaster Hal Jackson and backed by theater owner Abe Lichtman, who lured players with higher pay and a lighter schedule.

After the war, a number of NBL franchises struggled, including the Detroit Vagabond Kings, who dropped out of the league in December 1948. Since the league needed a replacement, the Rens moved to Dayton, Ohio, and finished the season with the NBL, becoming the first Black-owned team in a primarily white league.

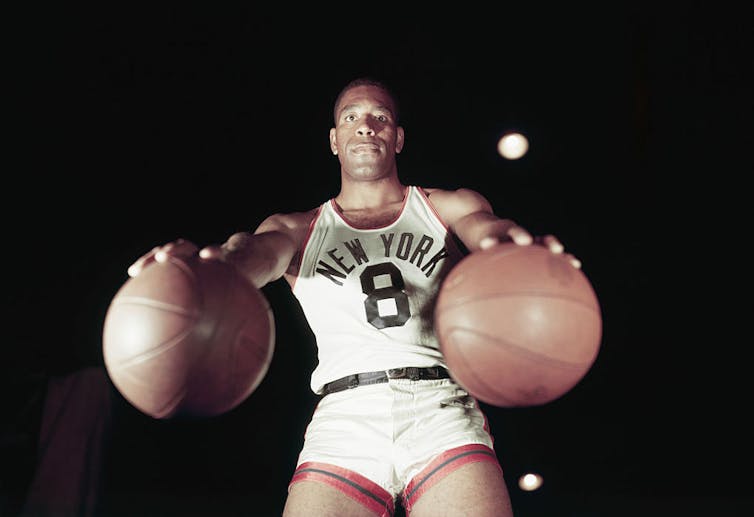

The NBL shuttered following the season, and several teams joined the newly formed NBA, leaving the Rens behind. The NBA was segregated during its first season after the merger was completed. But in 1950, several Black players – including former Rens player Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton – integrated the league.

As professional sports grew and continued to integrate over the course of the 20th century, all-Black teams lost much of their top talent to white-owned teams. Despite quotas that limited the number of Black players on white-owned teams, the loss of top talent led to the end of teams like the Rens.

The unique community and fan experiences fostered by these all-Black franchises was forever lost.

The Rens legacy

In 1963, the 1932-33 Rens squad was enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame. Several individual players, along with Douglas, would enter the Hall in later years.

Today there are no Black majority owners in any of the four major North American professional leagues. There are a handful of Black Americans who are minority owners of teams – former NBA stars Dwyane Wade and Grant Hill have minority stakes in the Utah Jazz and Atlanta Hawks, respectively – but it isn’t clear how much influence they wield.

It’s an especially discouraging situation for the NBA. In a league that is over 70% Black, the dearth of Black owners and executives can lead to a disconnect between the players and the people running the league.

In recent years, players have clashed with owners over dress codes, discipline and political protests.

As league revenue continues to soar, and the NBA serves as an example for inclusive hiring practices, the lack of Black ownership is harder to ignore 100 years after the Rens first stepped on the court.

Jared Bahir Browsh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.