Katherine Shepard describes the shot that killed her boyfriend Matthew Willson as an “absolute freak of nature”.

The single bullet travelled 200 metres from a tree-lined park next to her apartment in Brookhaven, Georgia, through a 10-centimetre gap in the handrail of a stairwell walkway, piercing her bedroom wall and headboard before striking Willson in the head as he lay in bed beside her.

“Crazy, isn’t it?” she told The Independent in an interview from her home in Athens, Georgia. “I’ll never be able to get my head around the probability of that happening.”

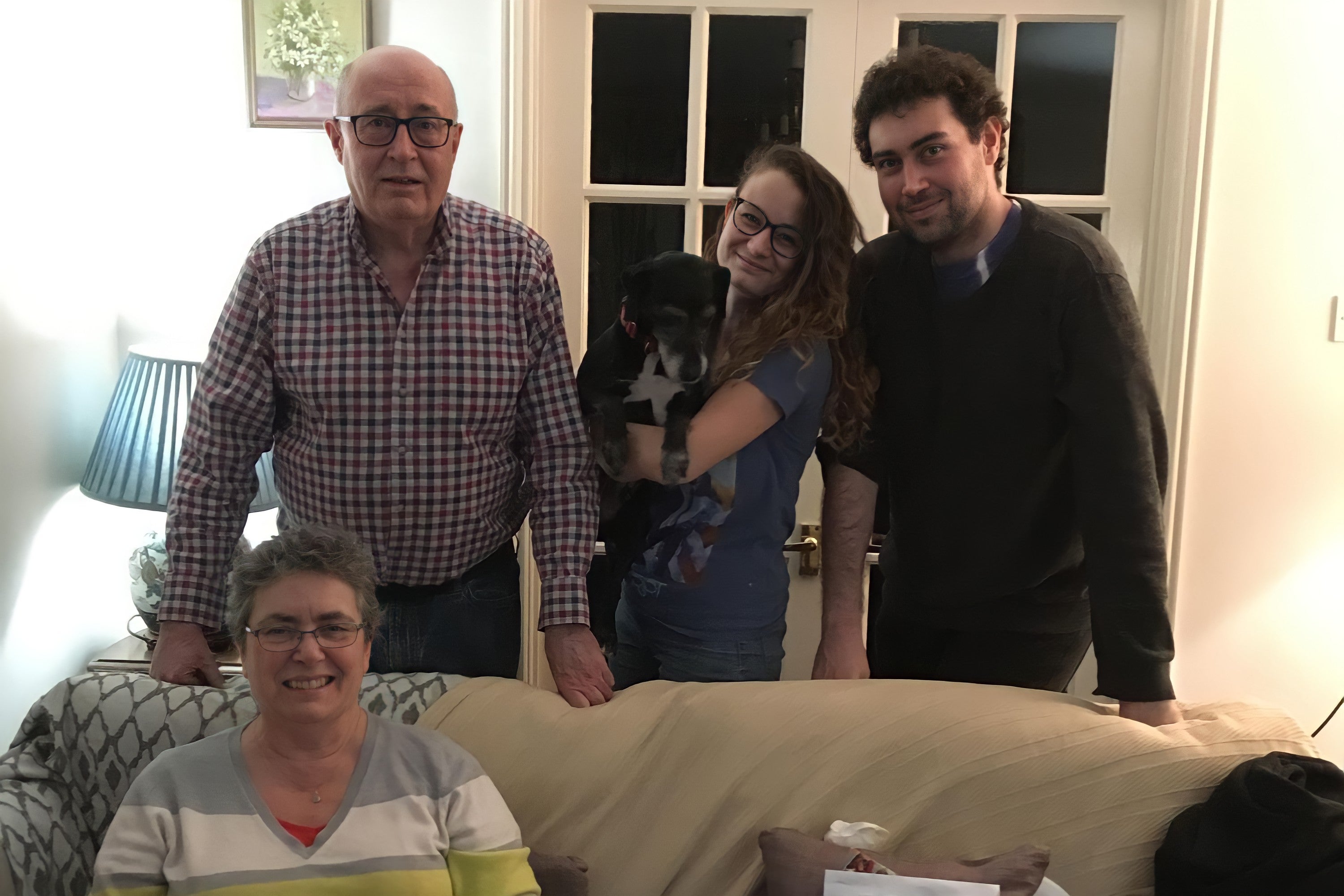

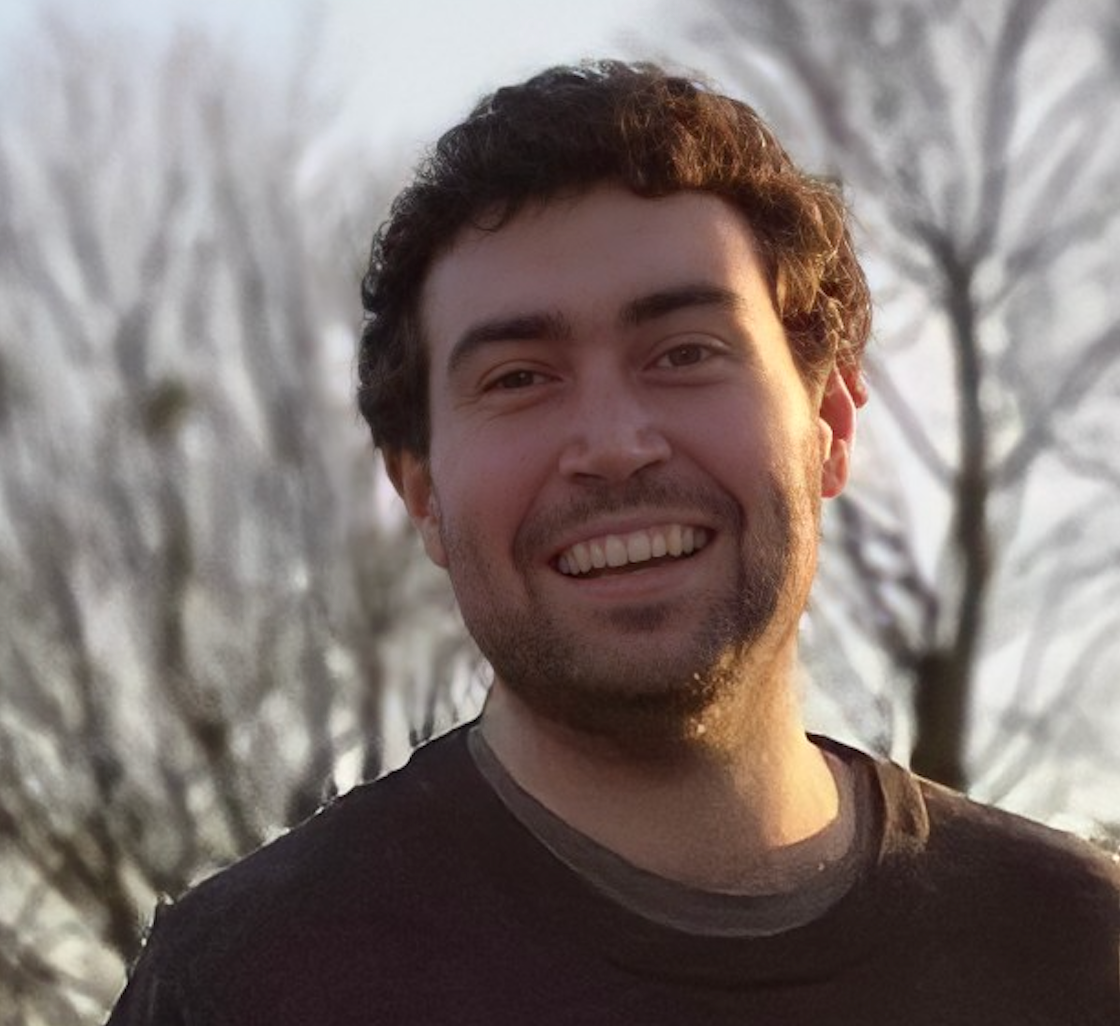

Willson, a gifted astrophysicist who grew up in England, had arrived in the US on 14 January last year to visit his long-term girlfriend of three years.

At 2am on 16 January, the couple were lying in bed at her home in the Park on Clairmont Apartments on Buford Highway, in northeastern Atlanta, when they heard shots ring out.

As the gunfire grew more intense, she called police.

“I’m sure they are just messing around,” Willson said to her as she reached for her phone, in what would turn out to be his final words.

Moments after calling 911, she heard an explosion beside her bed and noticed a piece of wall hit her leg. She turned on the light to see Willson slumped on the bed, bleeding from the head.

Ms Shepard tried to staunch the flow of blood from his head as she waited for an ambulance to arrive, urging him to “stay with me” as he struggled for breath.

He clung to life long enough for his sister Kate Easingwood to fly to the US from her home in Sweden, and for his heart, liver and kidneys to be transplanted to desperate patients on a local donor waiting list.

‘Do they even know?’

Sixteen months after Willson’s senseless death, police have yet to identify any suspects or find the weapon used.

Ms Easingwood told The Independent in an interview from Sweden that she still doesn’t even know if his killers are aware of his death, and the anguish they have caused.

“We obviously want the person responsible to be held accountable for what they’ve done, but also to know what they’ve done,” Ms Easingwood said.

“That’s a question that hangs over us, do they even know that they took someone’s life that night?”

Willson’s family this week contributed $10,000 (£8,000) for information leading to his killers, on top of $15,000 (£12,000) offered by Atlanta Crime Stoppers last year.

She hopes that the increased reward, and knowing of her brother’s selflessness in life, and in death, might spur someone to come forward with information.

“Four Americans live on today because of his death,” Ms Easingwood.

“Maybe somebody knows something, maybe they could come forward to help us get justice for Matt, but maybe it can also benefit them to have a better life.”

Ms Shepard met Willson at Georgia State University in 2018 while they were both studying astrophysics, she a first year, and he doing a post-doctoral research.

They bonded over a shared love of music and similar world views, and quickly became inseparable.

“We used to joke that it was really scary how similar we were. It felt like we were almost the same person, just different genders,” she told The Independent.

The pain of his death has barely rescinded in the past 16 months.

“We didn't have a breakup, I never had that closure and I’m incapable of calling him my ex. I really feel like a part of my heart died with him that night,” she said.

Willson’s killing also sent a shockwave through the tight knit world of astronomy, where he had worked on developing computer programmes to help scientists remove atmospheric effects that taint their data.

Ms Shepard, an astronomer, explains that space scientists are often trying to study faraway planets and solar systems “through this giant haze of air and water”.

“And it can be a real problem. That was what he was working on for a while, and he was making significant headway.”

Willson had been preparing to publish his research on the development of software tools for the European Extremely Large Telescope at the time of his death.

‘A pioneer in the realm of imaging young planets’

Growing up in the historic English market town of Chertsey, Surrey, 29 kilometres southwest of central London, Willson’s lifelong fascination with the stars began when he was just a toddler, Ms Easingwood recalled.

“He was always reading and learning. He wanted to know everything about everything,” she said.

His childhood fascination with the night sky led him to astrophysics, a branch of science that explores the birth, life and death of stars.

According to NASA, the area seeks to answer three broad questions: how does the universe work, how did we get here, and are we alone?

Willson’s academic career initially took him just up the road from his family home to Royal Holloway, University of London, where he began an undergraduate degree in 2008.

There, Willson helped design and construct a 30-centimetre telescope and would lead students on cold evenings as they searched for celestial discoveries, according to an obituary in the The Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.

After graduating with a Master of Science in 2012, he entered the PhD programme at the University of Exeter the next year, where he developed specialist equipment to study planets beyond the Solar System.

He graduated from the university in the summer of 2017 and moved to Atlanta to work as a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia State University’s Physics and Astronomy Department.

In Georgia, Willson once again threw himself into his studies, becoming an expert in high resolution imaging from ground-based telescopes.

Family say he made friends wherever he travelled. In Georgia, he played five-a-side football and hung out with the Official Liverpool FC Supporters Club in Atlanta.

When Willson moved to Belgium in 2019 to take up a post-doctoral position at the University of Liège, he and Ms Shepard continued to text every day, and Skype several times a week.

“If there ever was a day where we didn't text, you know, one of us would shoot the other a good night, or I love you message,” she told The Independent.

At an academic memorial after his death, every one of Willson’s supervisors read a eulogy for him, paying tribute to his kindness and research acumen.

“He will be remembered as a pioneer and explorer in the realm of imaging young planets,” an obituary in the American Astronomical Society read.

Ms Easingwood said it was only after her brother’s death that she fully understood the esteem in which he was held by his peers.

“He was a selfless, wonderful person who had a shining career ahead of him that was taken away.”

‘It doesn’t seem sane in any way’

Ms Easingwood remembers feeling apprehensive about her brother’s move to the US. She told The Independent she found the gun culture “terrifying”, and completely alien to their idyllic English childhood.

When she travelled to the US after her brother was shot, she said she immediately felt unsafe, and has no plans to return.

“You hear about shootings in the US, you know that there’s a gun problem but you don’t expect what happened to Matt to happen. It takes away your sense of safety and I haven’t got that back yet.

“Our impression from here is that it is out of control. When you look at the statistics, there’s no other way to describe it.

“The way the US is handling it doesn’t seem sane in any way. To have kindergarten children doing drills and being taught to play dead on the floor, that’s insanity right?”

In Sweden, the death of 60 people to gun violence in 2022 prompted a national reckoning.

In 2021, the last year that full statistics are available, 48,830 people died from gun-related injuries in the US, according to the CDC.

Willson’s parents Pauline Willson and Robert Easingwood were unable to make the trip to the US to see him one last time as his mother was ill with cancer. She passed away just a few weeks ago at the end of March.

“In her last few weeks, she was in a lot of pain from the cancer, but the absence of her son was almost more consuming for her than the actual physical pain she was experiencing,” Ms Easingwood told The Independent.

Ms Easingwood, a molecular biology PhD student, has been on long-term sick leave since her brother’s death.

She says that milestones with her son Tyko, who was four months old when Willson was killed, have been difficult to celebrate. She’s six months pregnant with her second child, another layer to the sadness around her brother’s absence.

“It feels like it gets harder the further away you get from the event, you get further away from a world that he existed in,” she said.

Ms Shepard said her views on guns have altered drastically since Willson’s death. Her family had always owned them for self defence, but now she despises them.

“I wish that somehow we could just get rid of all of the guns in this country,” she said.

“I don't think that anything positive will happen with gun control in this country until some horrific events convinces the majority of the party that primarily supports the right to bear arms to act.”

She would like the American public to know the impact that a single, senseless act of violence has had on so many people.

“Whoever did this was so wrapped up in their own world, that they’ve completely destroyed this life and affected so many other lives.

“We’re still here and we’re still struggling with it, a year and a half later.”

Sergeant Kessel told The Independent in an interview that their efforts to trace the killers had so far failed to throw up any concrete leads.

So last year, the department’s criminal investigation division started sending every shell casing recovered from nearby crime scenes to the The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ National Integrated Ballistic Information Network in the hope it would lead to a breakthrough in the investigation.

There, the samples are compared against the network’s giant database of 5.7 million pieces of ballistic evidence in the hopes of finding a match.

The shell casings are analysed much like a fingerprint would be, he explained.

Sgt Kessel told The Independent that Brookhaven detectives also routinely press suspects for information about the unsolved case.

“When an arrest is made along that corridor where they have that firearm, or we have reason to leverage them in an interview, we always ask if they have any information about the Dr Willson shooting to see if we hopefully one day might have the right person in the interview seat and obtain the right information,” he said.

He added: “We’re hopeful that the hard work will eventually pay off. We’re strapped in for the long haul.”