Between Godzilla x Kong, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, and Monkey Man, it’s been a big year for blockbuster movies about humanity’s closest genetic relatives. But even with some fierce primate competition, there’s no denying that Kong is still king in Hollywood — with the box office numbers to back it up.

As the undisputed champion of gorilla cinema, it’s easy to assume that King Kong invented the genre back in 1933. In reality, however, apes and gorillas were already a common theme in early Hollywood. Kong’s main contribution was making the gorilla really, really big (which, to be fair, turned out to be a winning formula), but the history of the genre is even weirder and darker than you might think.

A Brief History of Cinematic Gorillas

Believe it or not, there was a time when apes were a more bankable movie monster than vampires or werewolves.

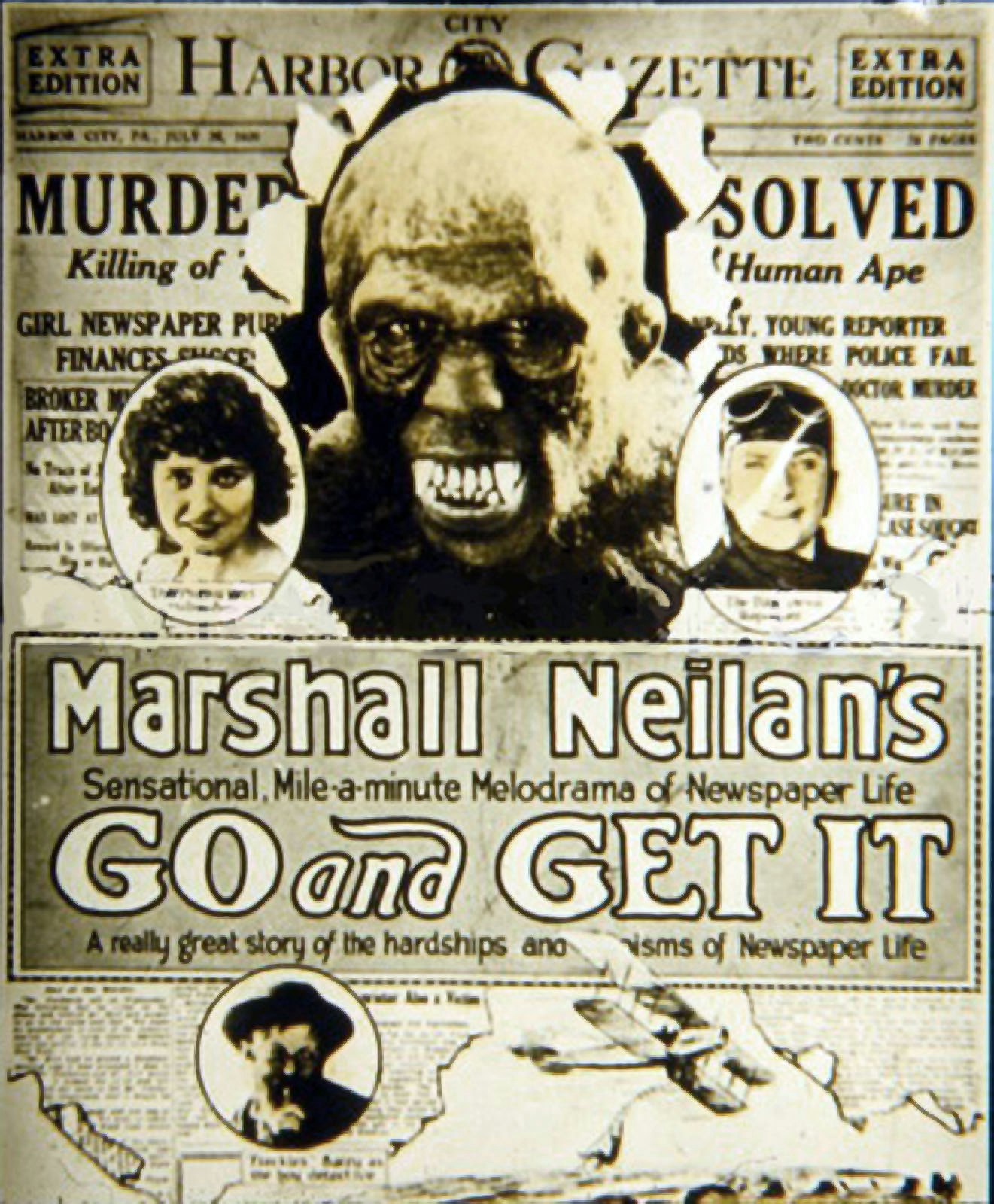

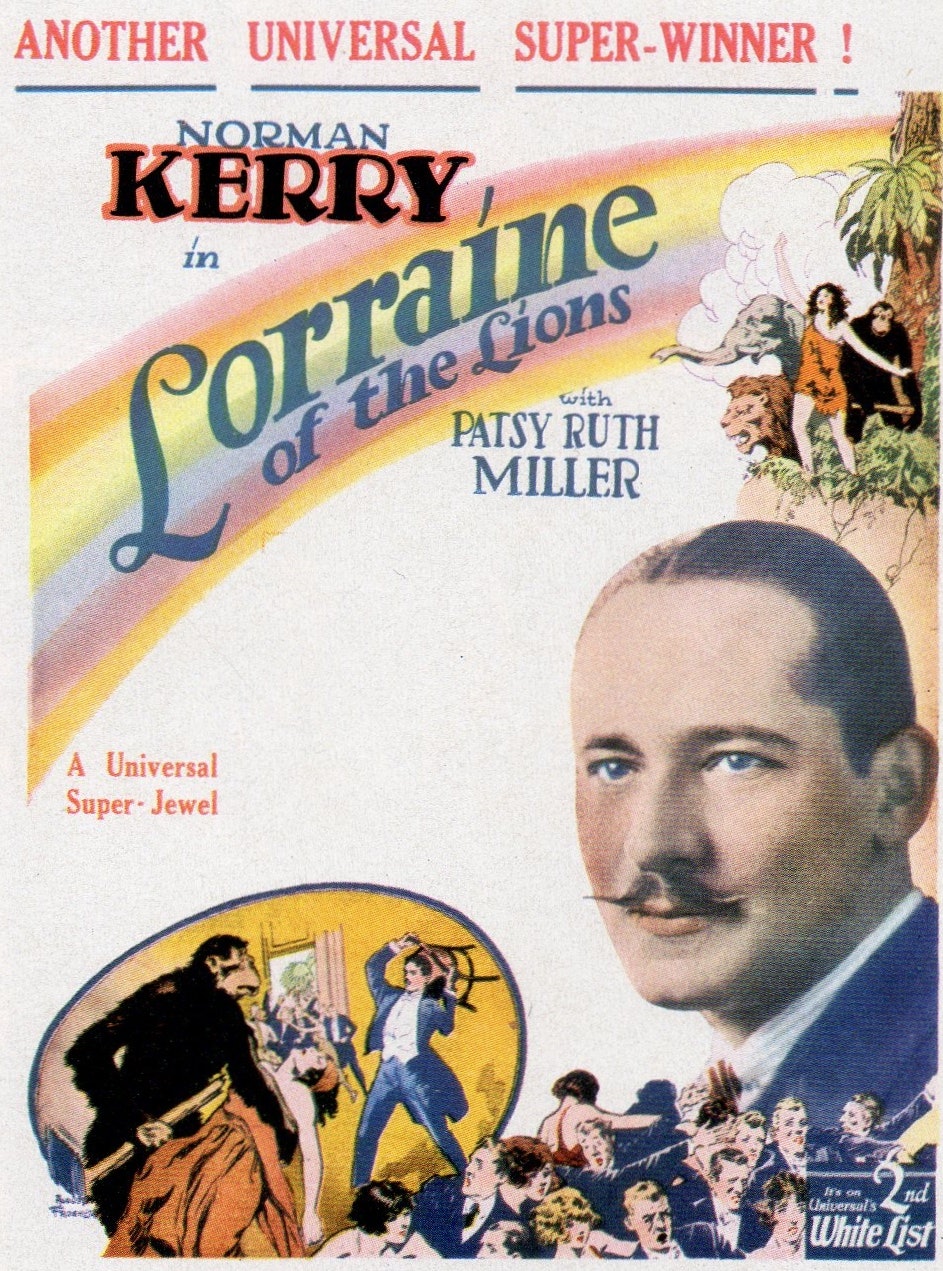

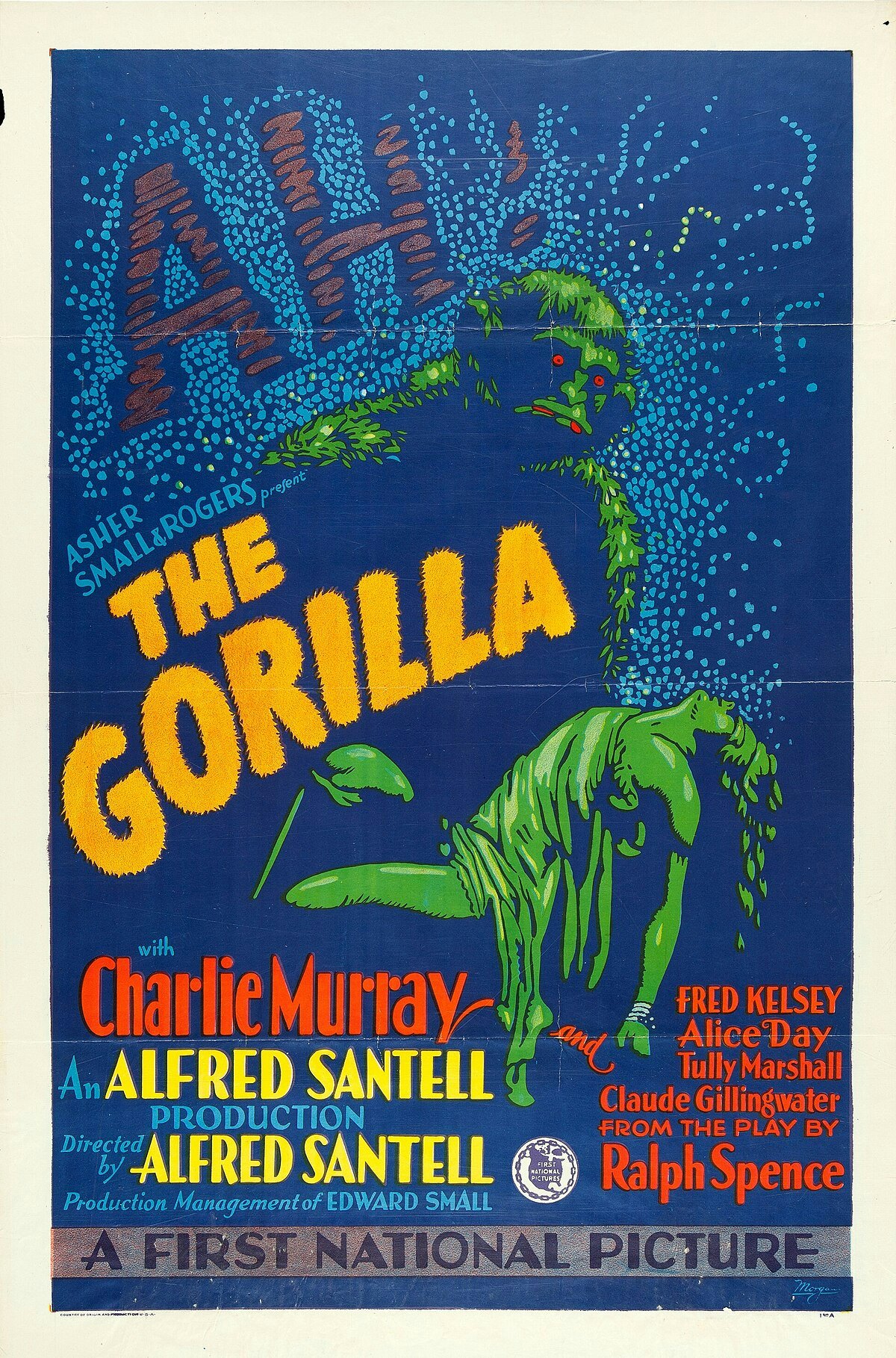

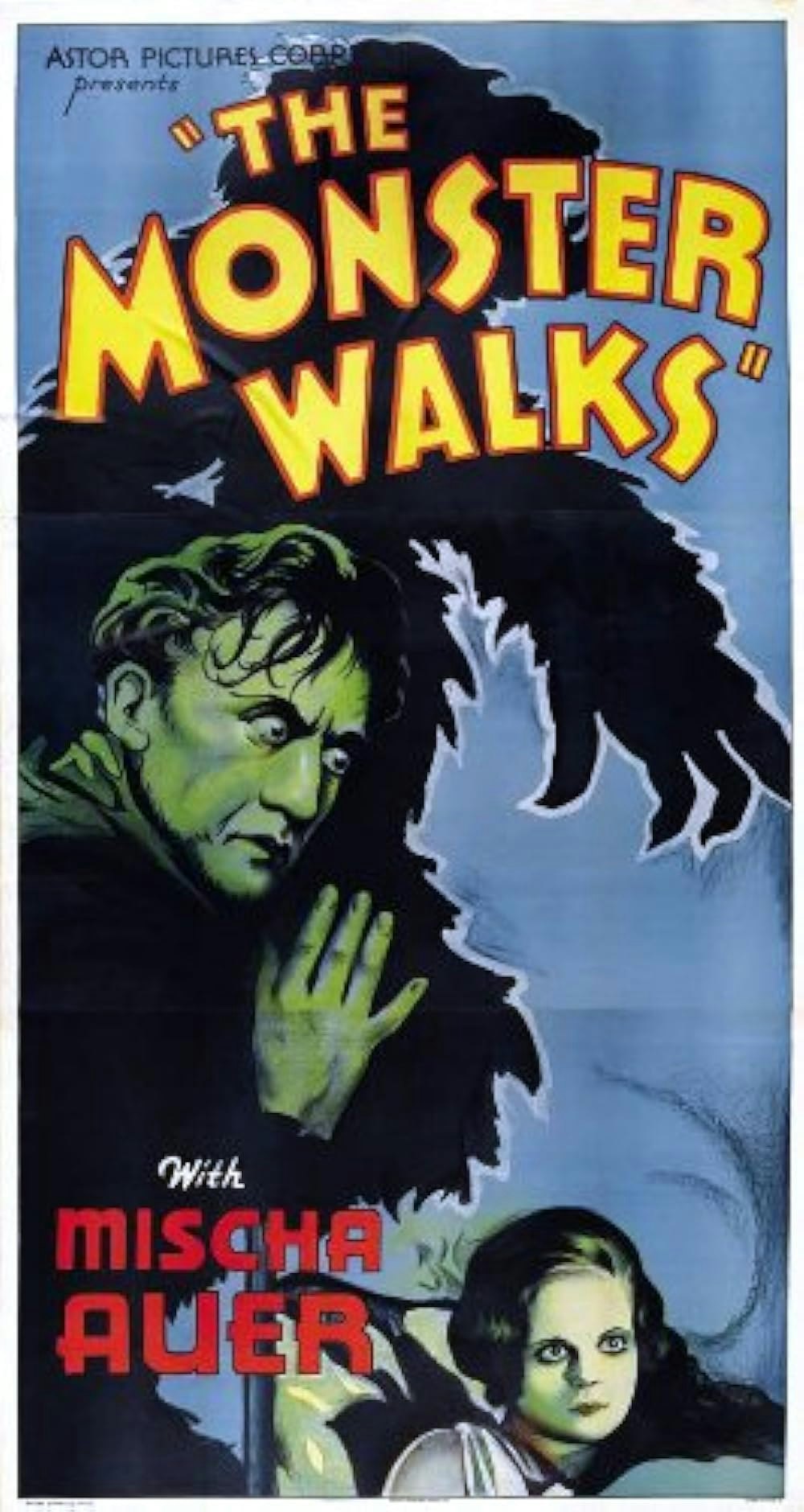

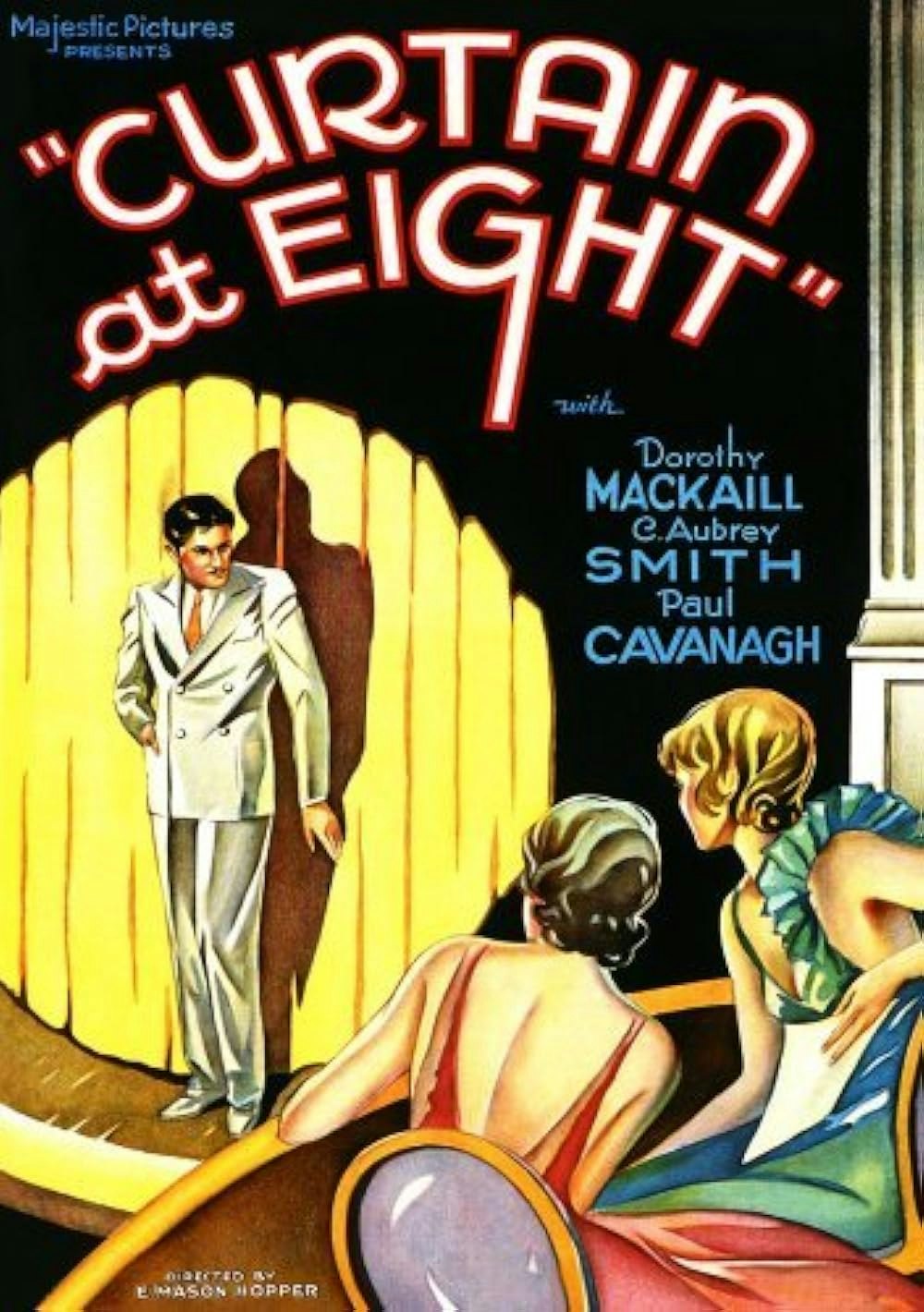

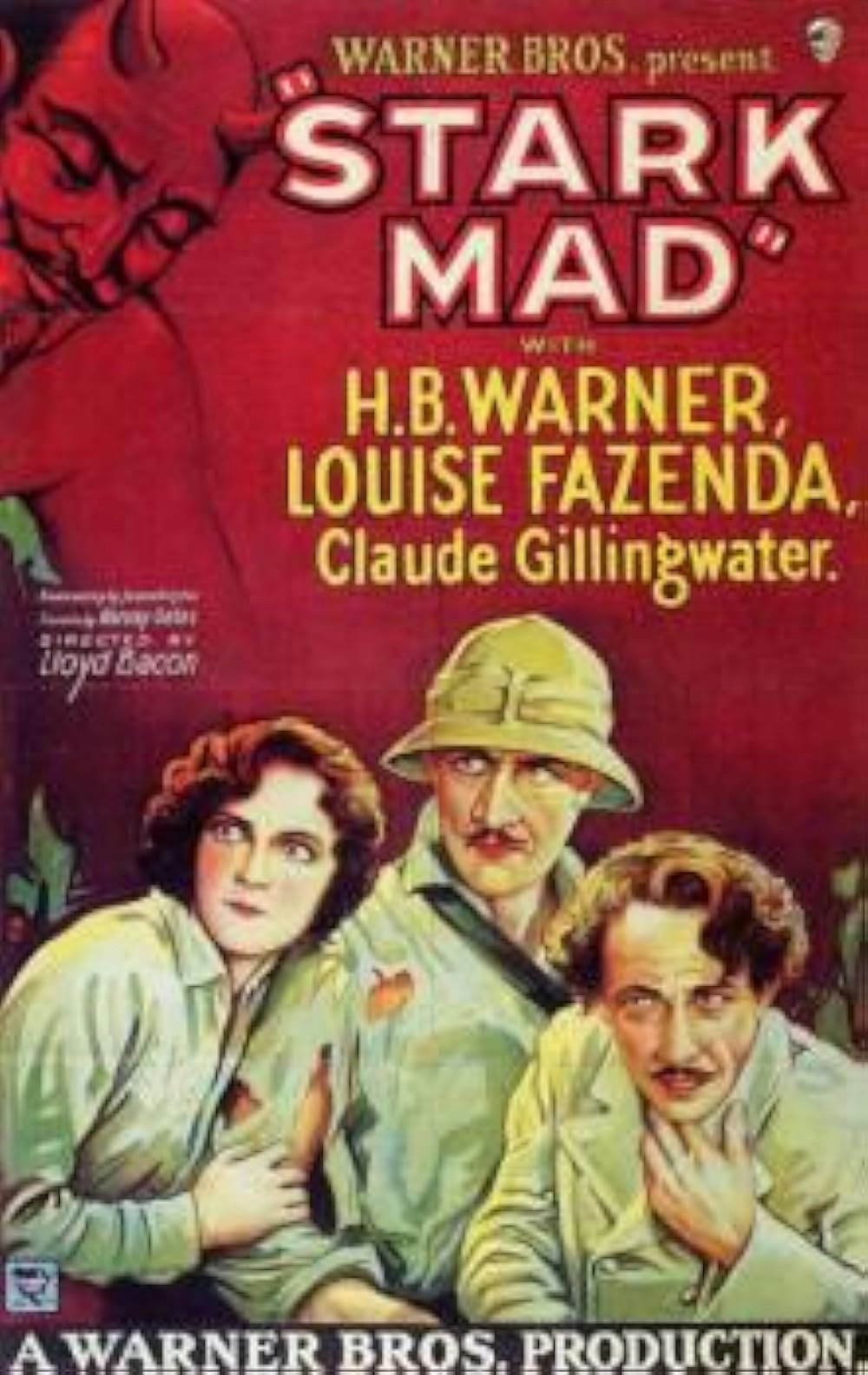

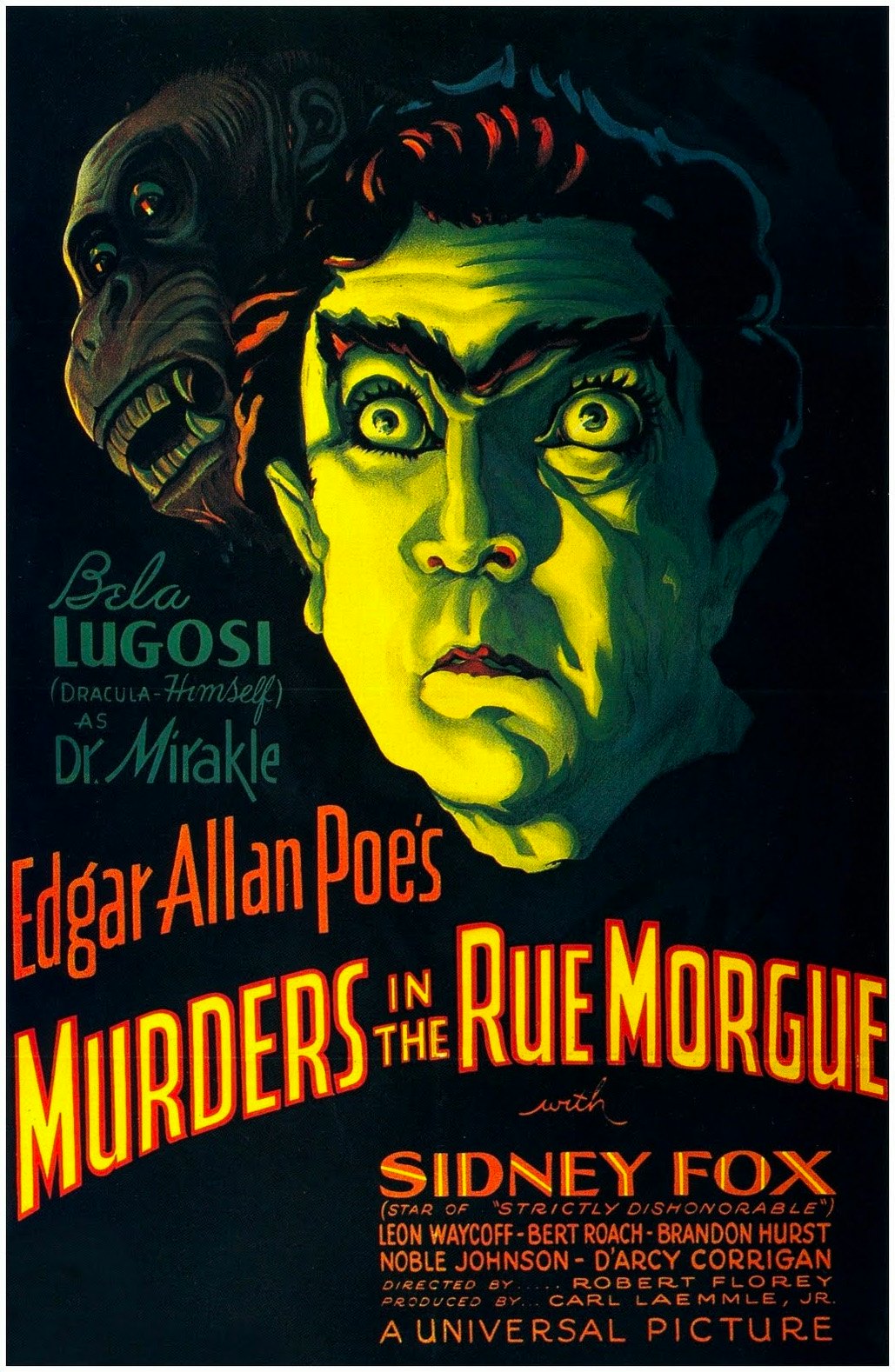

Overlapping with the popularity of jungle adventure stories and circus acts featuring apes and monkeys, 1920s and ’30s Hollywood had a gorilla movie for every occasion. In the silent film Go and Get It (1920), a mad scientist transfers a criminal’s brain into the body of a gorilla, who then embarks on a killing spree. In the Tarzan-like Lorraine of the Lions (1925), a shipwrecked girl grows up with a wild gorilla and his animal pals. The Gorilla (1927) is a murder mystery where the killer wears a gorilla costume, 1932’s The Monster Walks centers on a killer ape, and the perpetrator in 1933’s Curtain at Eight is a homicidal chimp. Stark Mad (1929) follows a group of explorers who discover a mysterious ape in a Mayan temple. And the Bela Lugosi horror flick Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) involves bizarre experiments to infuse human women with ape blood, culminating in an action sequence where the ape (like Kong) carries a woman across the rooftops.

There’s also a whole cavalcade of circus and jungle movies where apes and gorillas play secondary roles. Not to mention the many films where gorilla imagery just sort of appears for no reason, like Marlene Dietrich’s gorilla suit cabaret act in Blonde Venus (1932). So when King Kong arrived in 1933, audiences were primed and ready for the ultimate gorilla blockbuster.

That 1933 release date was a crucial factor in King Kong’s success, arriving during a brief period of relaxed censorship for American cinema before the Hays Code cracked down on sex, violence, and immoral themes in 1934. Known as the pre-Code era, the early ‘30s welcomed a flood of bold, dark, and boundary-pushing films. Unsurprisingly it was a great time for horror, launching most of Universal’s classic monster franchises (Dracula, Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, and The Mummy) along with other classics like the disturbing 1931 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (where Hyde resembles an ape-man). After 1934, American horror movies faced stricter censorship. King Kong premiered just before the Hays office tightened its restrictions and features some startlingly gruesome scenes that were edited out of later screenings.

Hollywood’s Original Gorilla King

From the very beginning, monkey movies have played into the gorilla’s status as a symbol of exoticized foreign danger.

During World War I, one of America’s most iconic propaganda posters depicted Germany as a snarling gorilla, toting a club in one arm and a half-naked woman in the other: Lady Liberty, kidnapped by German aggressors. The slogan reads “Destroy this Mad Brute.” The imagery is unmistakably similar to King Kong and numerous later films where gorillas kidnap women.

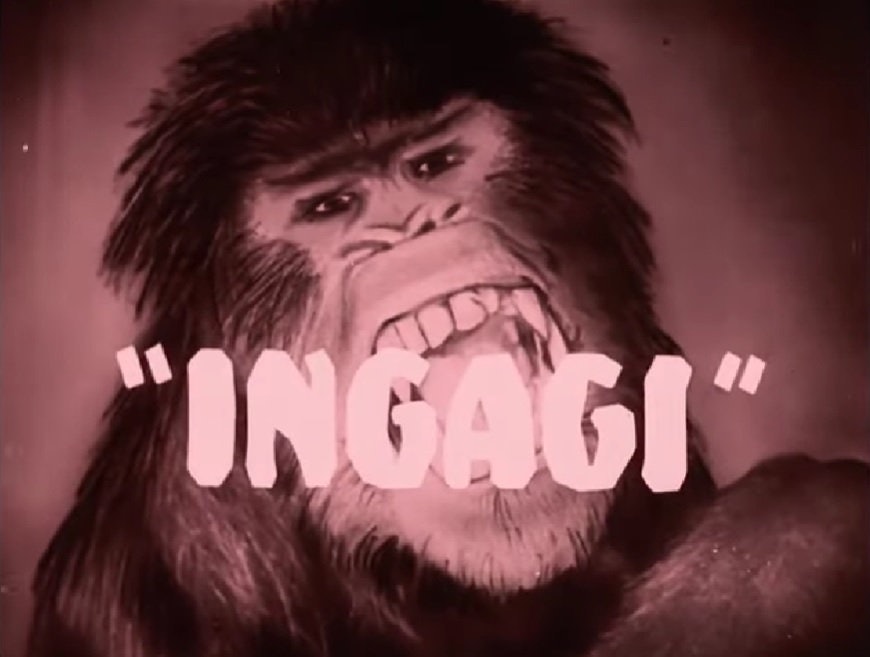

This sexual undertone comes up again and again in vintage gorilla films, depicting apes as an inhuman menace to young women. The most notorious example is Ingagi, a horrendously racist exploitation movie that caused uproar in 1930, and likely fed into King Kong’s success.

Ingagi was marketed as a documentary, capitalizing on the popularity of ethnographic travelogs, a subgenre that introduced U.S. audiences to far-off locations and cultures. (In many cases this was a thinly disguised excuse to film topless indigenous women from Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, disguising exploitation as educational nonfiction.)

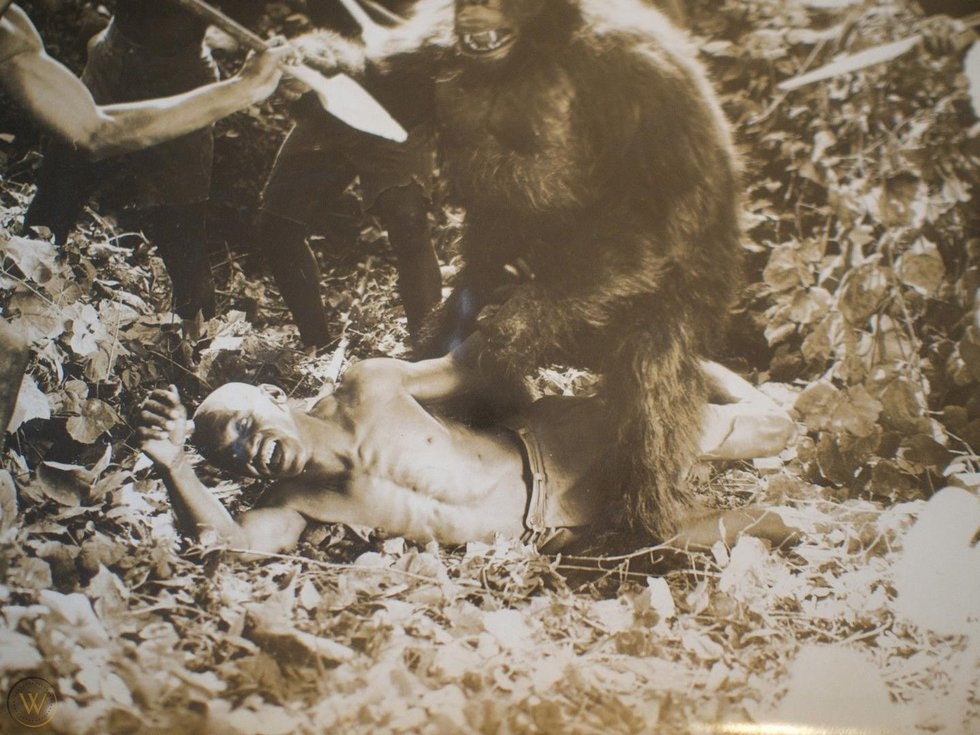

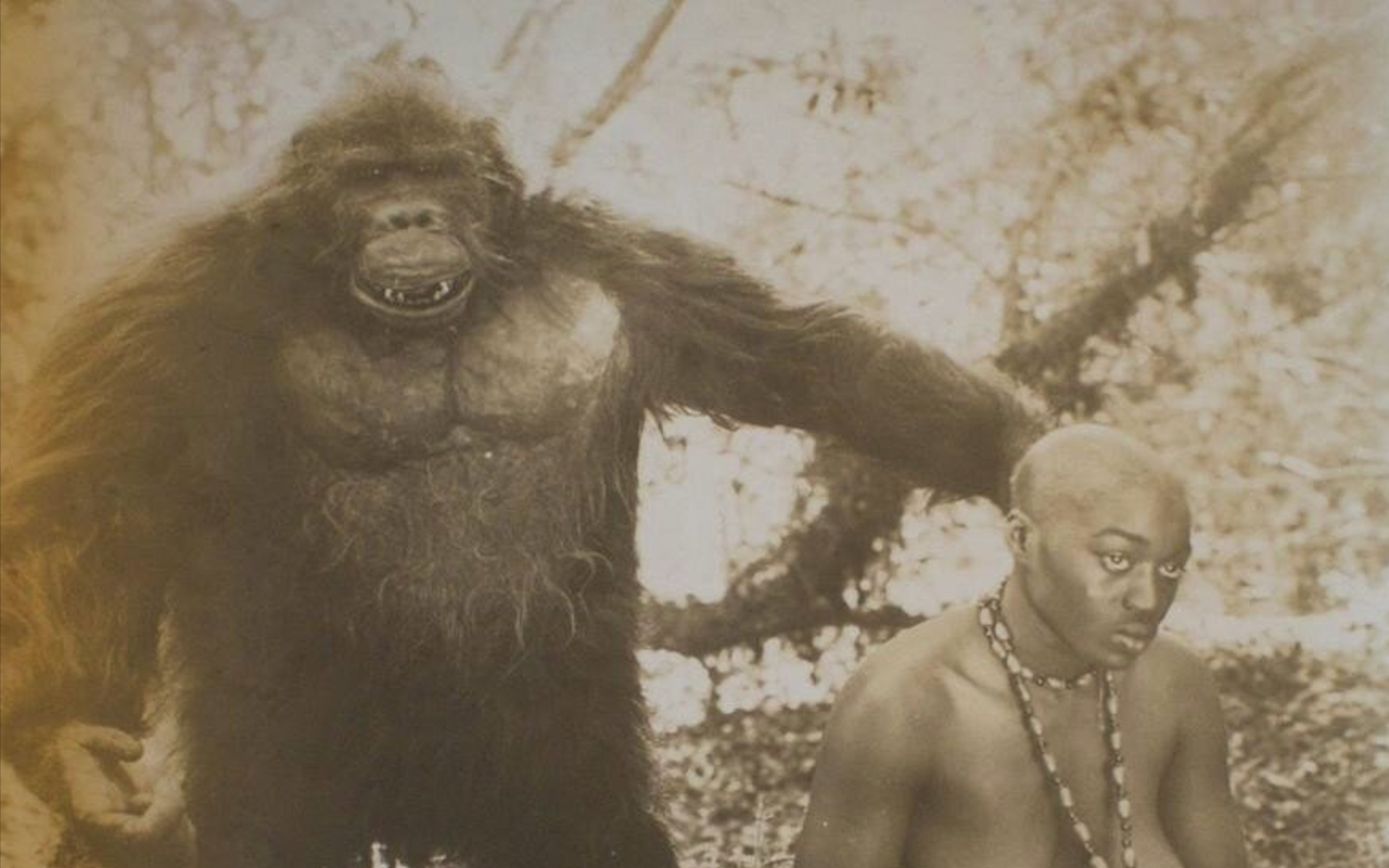

Produced on a low budget by independent filmmakers, Ingagi combined footage from a 1915 wildlife documentary with fictional scenes filmed in Los Angeles. Echoing that old WWI propaganda image, its posters depicted a gorilla clutching a topless woman.

The film claimed to reveal a “real” tradition in the Belgian Congo, where women were supposedly sacrificed to a gorilla — and then had sex with it. Steeped in racist ideas, it was a shameless exploitation movie featuring full-frontal nudity — something that government censors quickly condemned.

Ingagi’s salacious premise sparked public fascination, coupled with accusations that the whole thing was a hoax. Which, of course, it was. While some parts of the film used real wildlife footage, the gorilla stuff was actually a man in a costume: Charles Gemora, one of several actors who specialized in ape/gorilla roles at the time. The African women and British explorer characters were played by American actors.

The Hays office soon ordered mainstream studio theaters to stop screening Ingagi, labeling the film a fraud. But Ingagi was already a hit, and it continued to play at independent theaters instead. Its publicity campaign leaned into its scandalous reputation, promising “wild women of the jungle” and their “half-ape, half-human” offspring. It was box office dynamite. Audiences were intrigued by the promise of bestiality, animal attacks, and naked women — regardless of whether the story was real or not.

While we can’t draw a direct line between Ingagi and the creative process behind Kong, there’s definitely some overlap — not just thematically, but on the business side as well. King Kong was produced by RKO, the same studio whose theaters made bank with Ingagi a couple of years earlier. Kong offered a more palatable (and competently filmed) take on similar ideas, drawing from a familiar pool of jungle adventure tropes.

In recent decades, Kong sequels and other giant ape movies like Rampage lean more toward the kaiju/disaster genre, while the Planet of the Apes franchise offers a more cerebral brand of storytelling. Like vampires, Westerns, and other classic Hollywood staples, the ape genre has evolved with the times, finding new ways to thrive after more than a century on the silver screen.