The deadly terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, prompted an outcry around the world: “We are all Americans.” Washington’s policies realigned around fighting terrorism and bilateral relationships strengthened or crumbled depending on where other governments stood. In the latest in a series about the legacy of September 11, Jodi Xu Klein recounts the memories of Betty Ann Ong, the Chinese-American flight attendant who raised the first alarm about the hijackings that day.

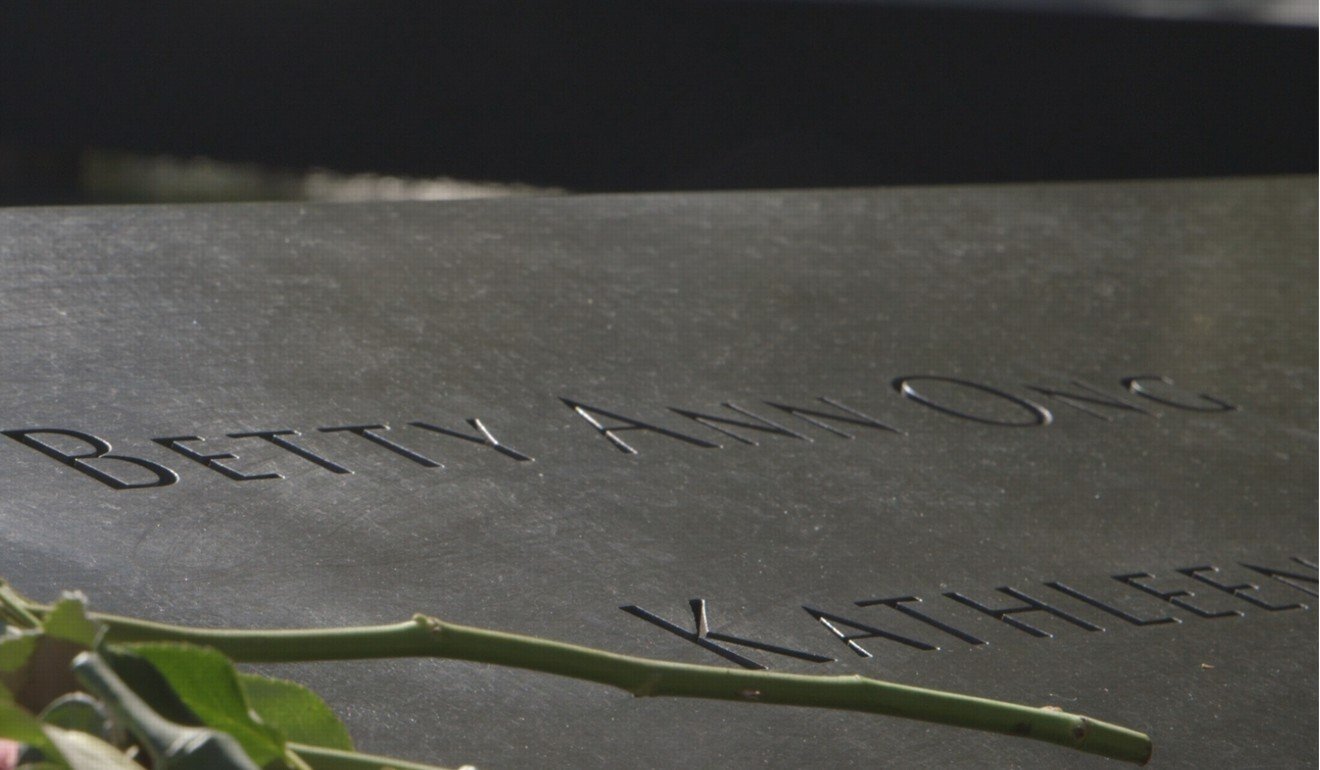

On a spring day in 2002, Cathie Ong-Herrera received a call from the New York City Medical Examiner’s office. At the base of where the North Tower of the World Trade Centre used to stand, she was told, a two-inch thigh bone and some soft tissue had been recovered and identified. They matched the DNA of Cathie’s younger sister, Betty Ann Ong.

These were all that was left of Ong, a 45-year-old Chinese-American flight attendant who was the first to alert authorities of the attacks of September 11, 2001, when nearly 3,000 lives were lost.

Five hijackers took control of American Airlines Flight 11, one of four hijacked planes that day, and the Boeing 767, heading out of Boston and intended for Los Angeles, detoured instead to New York. During the last 25 minutes of her life, Ong, using the aircraft’s emergency line to speak to ground crews, calmly provided information about the hijackers and injuries to passengers and crew. When the jet crashed into the North Tower at 8:46am – the first of two planes to fly into the towers – at 755km an hour (470mph), Ong, along with the other 10 crew members and 81 passengers, died.

But her early, vital and detailed account of what was occurring helped the US government realise the extent of the day’s attacks by al-Qaeda. The Federal Aviation Administration took the unprecedented step of grounding flights nationwide.

In 2004, Ong was declared “a true American hero” by Thomas Kean, chairman of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, better known as the 9/11 Commission.

Her family takes that recognition as a great solace.

“Betty was an American. She is considered a hero because of what she did,” Cathie said last week. “The US when September 11 happened was a country where we were all one. We were all helping each other.”

But 20 years later, Ong’s family still grieves for a loved one whose life was cut brutally short.

Born on February 5, 1956, Betty – known in the family as Bee – was the youngest of four siblings in the San Francisco household of Chinese descent. Betty, along with her two sisters Cathie and Gloria, and their brother Harry, were third-generation Americans. Both sets of grandparents had emigrated from China sometime after World War I. Her father, Harry Ong Sr, and mother, Oy Yee-gum, ran a popular jerky shop in Chinatown.

Growing up in the city’s Chinatown, the sisters would travel to San Francisco International Airport to watch planes take off. Always fascinated by travel, Betty began her aviation career in the baggage claim department with PSA Airlines in the 1980s, then with Delta Air Lines as a ticket agent.

It wasn’t until 1987 that Ong became a flight attendant with American Airlines, a dream job. It was her choice to fly mostly between Boston and California so she could come home to San Francisco.

As a family, the Ongs are tightly knit, so close to one another that the entire group – parents and siblings alike – would go shopping together for someone’s shoes. When Betty joined American Airlines, the sisters would go on trips together.

That summer of 2001, the sisters were planning another trip, this time to Hawaii.

In a long last email to Cathie, Betty said she was working extra flights so she could go on the trip.

“Silly me for working so hard,” Cathie recalled Betty writing.

That was September 9. Betty offered to take a September 11 shift for a colleague – ending up on Flight 11.

When Flight 11 crashed, Cathie had barely started her day in Bakersfield, California. She and Betty were supposed to meet for lunch in Los Angeles later that day to discuss their plans for their first “sister trip” since visiting Tokyo together more than 10 years earlier.

Early that morning, Cathie’s phone rang. It was Harry, who, she said, told her to turn the TV on because “an historical event was taking place.”

As the siblings watched the stunning scenes, considering the two smouldering towers to be simply a news event, Harry asked Cathie where Betty was. He said he’d heard that the planes that had flown into them were flights originating in Boston.

“My heart sank,” Cathie said. “I called Betty’s cell phone and received a busy signal and it gave me hope that she was trying to call us to tell us that she was OK.”

Throughout the day, they tried desperately to reach her and get information from the airline; Cathie grew too agitated to stay put. She and her husband decided to drive up to her parents’ home in San Francisco. Somewhere during the trip, she heard an American Airlines ground crew member say on a news report that somebody from Flight 11 had made a phone call, giving reports of the hijacking.

How September 11 changed aviation security forever

“When I heard that, I knew that if Betty was on that plane, it would be her because she was just that kind of person, brave and helpful,” Cathie said.

The next call Cathie got from Harry was bad news: American Airlines confirmed that Betty was on the plane.

“I remember telling my husband that I needed to get out of the car so we pulled off into the parking lot of a mall. And it was about 8 o’clock at night and I was just shocked, crying, and looking up at the sky and shouting ‘why, why, why!’”

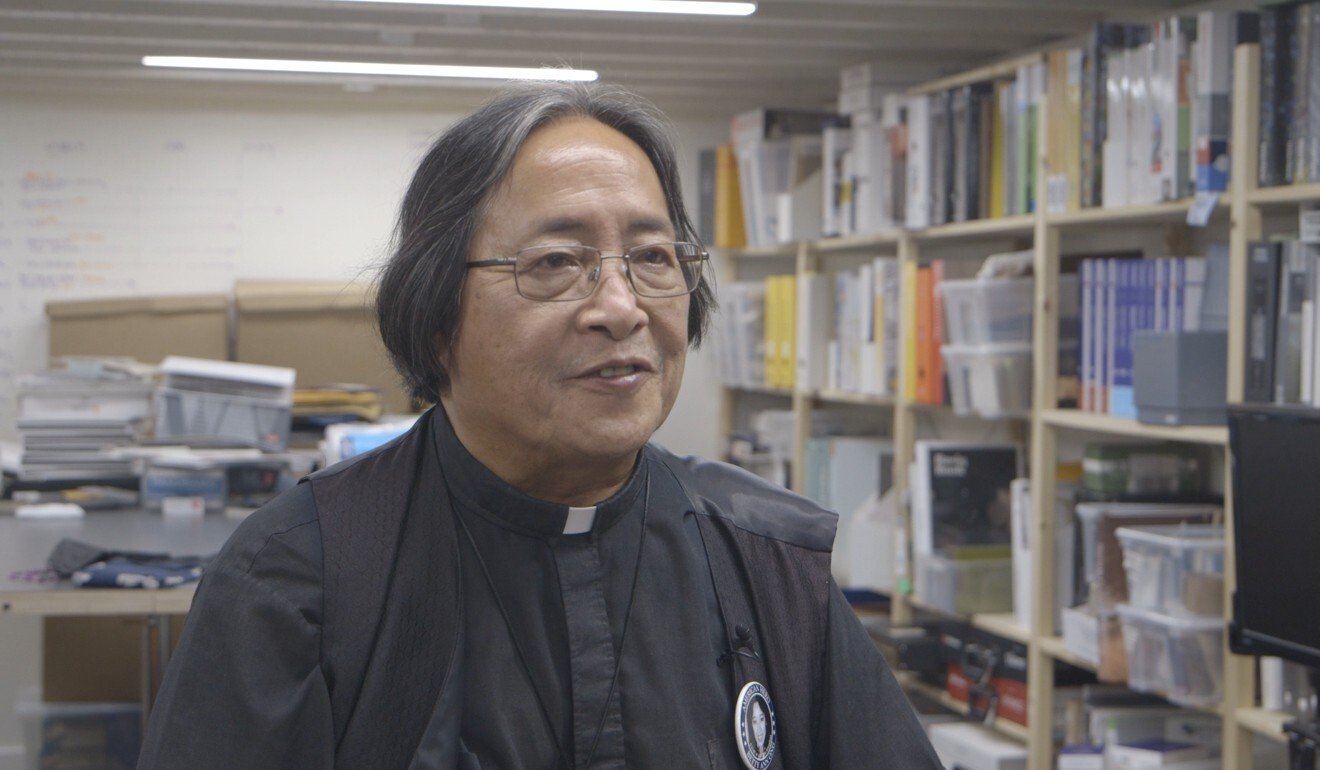

When they got to her parents’ house, Reverend Norman Fong, a minister at Chinatown’s Presbyterian Church, was already there. Fong was Cathie’s oldest friend since childhood but they had not been in touch in years.

Fong became a driving force behind a decade-long campaign to commemorate Ong.

“It was difficult. She wasn’t recognised as a hero at first,” recalled Fong, 69, who retired recently as the executive director at the San Francisco Chinatown Community Development Centre. He and the family wanted a building named after Betty, but repeated attempts to rename one of the public schools Betty attended failed.

Fong didn’t give up, though, and solicited support from the San Francisco recreation and parks department as well as then-mayor Ed Lee to rename the Chinatown community centre in her honour.

The newly renovated Betty Ann Ong Chinese Recreation Centre reopened in the summer of 2012; the sprawling 2,230 sq metre (24,000 sq ft) facility hosted a wide range of events for children and senior citizens alike until the pandemic restricted activities.

In 2004, Cathie created the Betty Ann Ong Foundation, which runs summer camps offering active living and healthy eating for children. The foundation now also raises funds for sports activities at the recreation centre.

“I want to mirror Betty’s spirit of her love for children. And I want to keep her legacy. All I knew was it would be about children because that was what Betty loved,” Cathie said.

For a year after her sister’s death, Cathie said, she was in denial. She didn’t want to talk to anyone about Betty because discussing her meant admitting that Betty was gone. So she made up a story that Betty was “walking around New York with amnesia and that she would soon come home to tell us that she was OK”.

In 2017 – 16 years after the Hawaii trip that never materialised – Cathie went to the Hawaiian island of Maui to speak about her sister at the Rotary club there.

“I thought about Betty a lot on the trip because that was where my sister and I were going to go. Talking to the audience about my sister in Hawaii was difficult, but it brought me some closure,” she said.

The family used to attend the September 11 commemorative events in New York City every year until recently, when it became too difficult for their mother, Oy, now 96, to travel across the country. When the pandemic hit, the family opted for retreats nearby.

Cathie, now 70, said that her sister’s death “made us as a family stronger. It made us closer than we were before.”

“We tell each other we love each other more. Almost every conversation ends with ‘I love you’. In that sense it changed us.”

It also gave the family pride: they know in their heart that because of what Betty did, many lives were saved.

“I figured Betty is in heaven, an angel there, for sure,” Fong said. “I would say ‘Thank you for what you did, not just for our country, but for all the Chinatown kids cross-country’. They have a hero, a beautiful hero.”

Fong, who came out of retirement this year to continue community work to battle anti-Asian hate, said it was heartbreaking to witness the rising anger aimed at Chinese-Americans.

He said that a group of teenagers in a car had recently yelled at him to “go back to China”.

“Until America sees the Chinese-Americans as Americans too, we still have a long way to go,” Fong said.

“Fear is the main enemy in life. There is a lot of fear from hate. Betty overcame her fear to help save America. A lot of us have to step up to help the most vulnerable,” he added.

Cathie said that every time she hears about hate crimes, she thinks about her sister’s heroism. “I can feel the pain the victims and the families of these violence must be feeling,” she said.

Betty’s recovered remains were buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California, on the San Francisco Peninsula. Cathie has lit candles for her sister since 2001. After their father, Harry Ong Sr, died in 2007, she’s lit candles for them both.

“I will light candles for Betty and my dad for the rest of my life every night. I stare up into the sky and talk to the stars. Many times, it’s very comforting because I see shooting stars and I feel that they are still with me.”

“In many ways, our family feels very fortunate because we know what Betty’s last moments were like because of her phone call,” Cathie said. “And there is some part of Betty that came home.”