The 2024 Paris Olympics aim to be the greenest edition on record, and the first compatible with the Paris climate agreement. Talk of “green games” goes back to April 2021. At the time, the Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG) had even aspired to carbon neutrality by removing more greenhouse gases from the atmosphere than those generated by the games. However, the reference to net zero was quietly dropped in subsequent communications.

Walking the talk

This begs the question: can the promise of “green games” be kept?

On paper, the Paris Olympics aim to halve the greenhouse gas emissions released by the Rio 2016 or London 2012 Games, estimated at an average 3.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Mt CO2 eq). That’s with the caveat that both games were among the least environmentally friendly in history. There have also been criticisms of the methodology used to calculate emissions, prompting the International Olympics Committee to release a standardised carbon footprint calculation framework for the Olympic games in 2018.

With this in mind, the maximum carbon budget for Paris 2024 has been set at 1.58 Mt CO2 eq. This is without a doubt an ambitious target, especially when we consider that the Tokyo 2020 Games, organised during a pandemic and without spectators, still generated almost 2 Mt CO₂ eq.

How the Olympics pollute

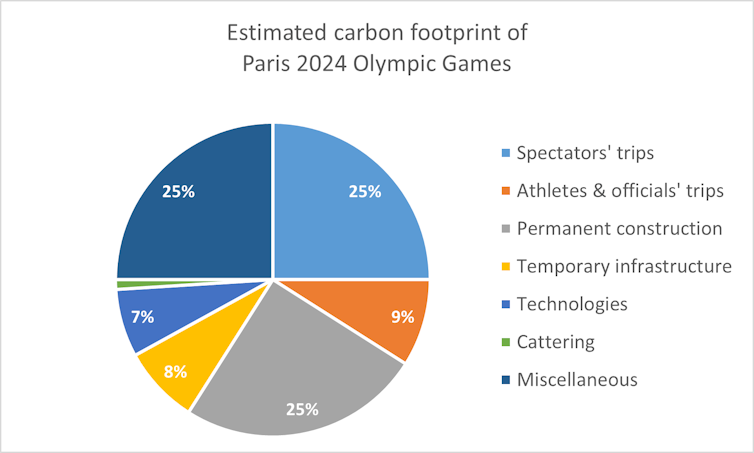

The biggest emission sources during mega-events are traditionally the transport of participants and the construction of buildings and infrastructure. The 2024 Olympics’ carbon footprint estimated to date breaks down into three relatively equal parts:

Travel by participants and spectators (which should account for a quarter of emissions, including 9% for athletes and officials),

Construction (with approximately 25 % for permanent buildings, including 8 % for temporary infrastructures, and about the same for temporary energy systems, such as generators)

Operations (catering, accommodation, logistics, security, etc), which account for the final quarter)

Naturally, we won’t know the exact carbon footprint of the 2024 Olympics until the event takes place. The quantities and types of construction materials have not been confirmed, and participation figures – currently estimated at around 13 million spectators – remain hypothetical. But the biggest unknown relates to transport. Air travel, potential rail strikes, as well as the delayed launch of four new metro lines set to connect the Paris region could all see emissions soaring.

And that’s without mentioning the the controversial construction of a new motorway junction for the Olympics. Research has long shown that the construction of new road infrastructure generated a lasting increase in traffic.

The Olympics Committee promises that the actual carbon footprint will be published in the autumn, after the games. It is hoped that the calculation of the carbon footprint will be communicated in a transparent and reproducible manner, and that the figure will have been verified by an independent third-party, which corresponds to good practice in terms of environmental reporting.

Greener games, really?

The 2024 Olympics organisers have pursued several avenues to slash emissions, most of which carry shortcomings.

The first resolution has been to limit construction. Of the infrastructure at the 26 competition venues 95% either already existed or is temporary. Any new building has also been designed to emit less CO2 than the average edifice.

A good eco-design example from the Paris Olympics is the aquatic centre, which boasts a wooden frame, photovoltaic panels on the roof, and seating made from recycled local materials. This last measure makes no difference to the aquatic centre’s carbon footprint, given the relatively small mass of plastic and its carbon footprint per kilogram compared with the mass and carbon footprint of other materials, notably concrete and metals. But the reduction in plastic waste and the positive impact on the local economy ought nevertheless to be applauded.

Set to greet 14,500 athletes during the Olympic Games and 9,000 athletes during the Paralympics, the Olympic village on the northern outskirts of Paris has pledged to a carbon footprint that is 30% smaller by comparison to a conventional construction project. There’s one hitch, however: the chosen benchmark – one tonne CO₂ eq per square metre – seems very high compared with the values found by specialist studies, which estimated the carbon footprint of European buildings in 2022 at 210 kg CO2 eq per square metre on average over its entire life cycle. Also concerning is the Olympics committee’s lack of specification on whether the target relates to the impact during construction only or over its lifecycle (including the subsequent use of the buildings).

The games are vying to be powered by 100% of renewable energy, including from photovoltaics, geothermal systems, biofuel-powered generators and certified renewable electricity – an option whose carbon benefit is, however, criticised by the scientific community.

In terms of catering, two-thirds of the meals served to fans and half of those for Olympic staff and volunteers will be vegetarian, halving their carbon impact compared with omnivorous meals, and 25% of the products will be local. However, bear in mind that the latter does not guarantee a lower carbon footprint.

Carbon offsets are also on the table. The OCOG is planning to finance reforestation, forest preservation and renewable energy development projects in France and abroad to offset 100% of the greenhouse gases emitted by the event. A commendable commitment, although we ought to note the real impact of carbon offsetting credits is widely disputed by the scientific community.

83 bottles of wine, 31 beef burgers

The research community is divided on the sustainability of mega-events. Some believe that their scale is incompatible with sustainability and that they mainly serve the financial interests and pleasure of the elite. Others see them as an opportunity for innovation, sustainable development and promotion of sustainability.

In concrete terms, the expected carbon footprint of the 2024 Olympics is 1.6 Mt CO2 eq for 13 to 16 million visitors, or around 100 to 125 kg CO2 eq per person. This is relatively small compared with the average annual carbon footprint of a European person, which stands at 7.8 t CO2 eq. For example, 100 kg eq CO2 is equivalent to the emissions generated by travelling 500 km by car or 10 000 km by metro, or consuming 31 beef burgers or 83 bottles of wine.

But to comply with the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to less than 1.5 to 2°C by 2100 compared with pre-industrial temperatures, we need to drastically limit everyone’s annual carbon footprint to less than 2 t CO₂ eq. It would be fair for rich countries, which are responsible for the vast majority of emissions, to shoulder the bulk of emission cuts.

Researchers have floated several ways to make mega-events more sustainable, from reducing events’ size, staging them in several cities to avoid building new infrastructures, to setting up independent sustainability standards and entrusting their assessment to independent bodies.

One fact everyone can get behind is that it’s time to reinvent the Olympic Games and mega-events to align them with international climate goals. Even better: the games could actively help their host region’s energy and climate transition, such as through urban regeneration. Host cities could use the opportunity of mega events to insulate buildings, deploy renewable energy infrastructure, better public and active transport infrastructure, or create urban leisure areas to lure back city dwellers who hit the road on the weekend to get away from the city. The legacy effects of the 1992 Barcelona Games are a wonderful example of successful urban renewal Paris could draw inspiration from.

Dr Anne de Bortoli’s research is funded by the CIRAIG, a research centre specialising in sustainability metrics at Polytechnique Montréal

Anne de Bortoli is a member of the Net-Zero Advisory Body for the Government of Canada and member of the scientific committee of Iceberg Data Lab.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.