In 1947, the United Kingdom was exhausted. World War II had ravaged its military and economy, and anti-colonial movements had begun to challenge empires. Within the Indian subcontinent, the U.K. faced two powerful, seemingly irreconcilable nationalist movements: one calling for the creation of Pakistan, a homeland for the Muslims of South Asia; the other for India, a pluralist democracy.

The U.K. chose to partition the region and withdraw. Under the terms of the Indian Independence Act, the subcontinent was formally divided into two new dominions at midnight of Aug. 14, 1947 – 75 years ago this month.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa.

Dividing a diverse land of hundreds of millions of people was far messier than the partition plan itself. Around 1 million people died, and more than 12 million were displaced, by the mass violence that broke out immediately afterward.

One particularly complicated piece of this history, which I have written about in my work as a scholar of Indian politics, is the fate of the regions known as “princely states,” which had some autonomy under the British. This dilemma still shapes the region, especially in Jammu and Kashmir, which has been ridden with conflict ever since.

Time to choose

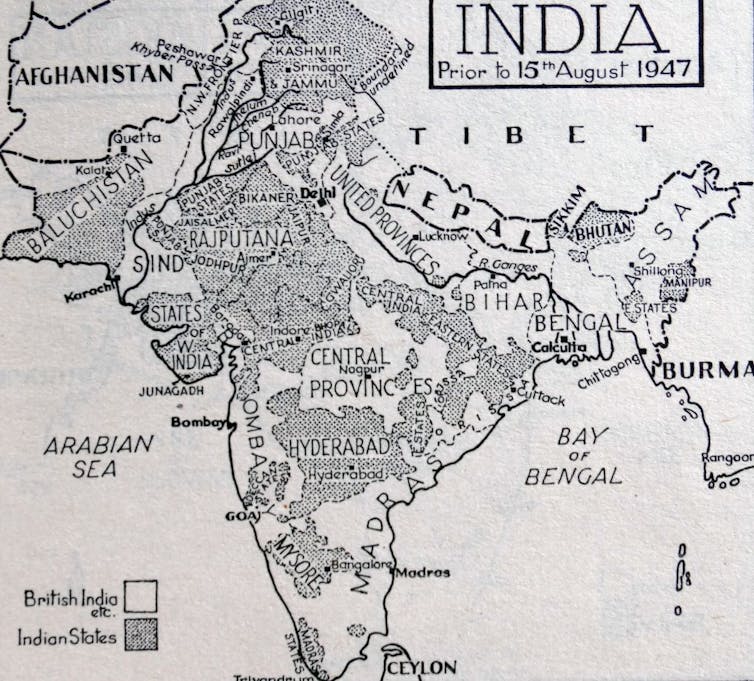

Under British rule there had been two classes of states. One set of states, those of British India, were directly ruled from London. The other, the “princely states,” were nominally independent as long as their rulers recognized the “paramountcy” of the British Crown.

Under the terms of this doctrine, these “princely states” could largely manage their internal affairs but had to defer to Britain on three critical policy issues: defense, foreign affairs and communications. Around the time of independence and partition there were approximately 562 such states, many of them quite small.

As the British prepared to depart, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last British viceroy – the British monarch’s representative in India – decreed that the rulers of the princely states had a choice: They could join either India or Pakistan. Independence, as an option, was effectively ruled out.

Moreover, Mountbatten added two important stipulations: that the states could be merged with India or Pakistan on the basis of demographic features and their geographic location. Accordingly, predominantly Muslim states would go to Pakistan and others to India. Finally, he also stipulated that states that were geographically situated inside the borders of one of the two emergent countries, regardless of their demographic composition, had to join that particular country.

Dragging their heels

The vast majority of the rulers of the princely states, despite harboring reservations about this plan, recognized that they had little or no choice and acceded to either India or Pakistan, though a few did have to be prodded or cajoled. However, a small number of them, for a variety of complex reasons, were reluctant to agree to the terms that Mountbatten had spelled out.

Three of them proved to be especially trying. The first of these was the monarch of Jammu and Kashmir, in the northwest. Maharaja Hari Singh was a Hindu ruling over a predominantly Muslim population. To compound matters, his state lay between the two emergent countries of India and Pakistan.

India, which was created as a secular state, wanted to incorporate Kashmir to demonstrate that a predominantly Muslim region could thrive in a Hindu-majority country committed to secularism. Pakistan, on the other hand, sought Kashmir because of its physical proximity and Muslim majority.

Singh was unwilling to cast his lot with either of the two states. He did not wish to join India because he was aware that India’s principal nationalist leader, Jawaharlal Nehru, had socialist leanings and would likely induce him to dispense with his vast landed estates. Simultaneously, he was averse to joining Pakistan because he was mostly at odds with his predominantly Muslim subjects.

Even after the independence of Pakistan and India was declared, Singh vacillated about which country to join. In October of 1947 a tribal rebellion broke out in Poonch, a district of Jammu and Kashmir. As his troops sought to quell the rebellion, the insurgents quickly found military support from Pakistan.

As the rebels approached his capital, Srinagar, Singh appealed to India for military assistance. Nehru, India’s first prime minister, agreed to provide assistance as long as two conditions were met. Singh would have to obtain the support of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, the leader of the largest popular and secular political party in the state, and he would have to formally sign the Instrument of Accession to India.

After Singh agreed to the conditions, India sent troops into the state, leading to a war with Pakistan – the first of four between the two countries, the most recent in 1999. The first conflict came to a close in 1948 with Pakistan gaining control over a third of Kashmir.

Neither country has wholly reconciled itself to Kashmir’s status. India claims the state in its entirety, as it became a part of its territory legally. Pakistan, however, has historically held the view that Kashmir was ceded to India by a ruler who did not represent its majority Muslim population. Indeed, this dispute between two nuclear-armed powers remains a potential global flashpoint.

Consequential choices

Another contentious case involved the Muslim ruler of the state of Hyderabad, well inside central India, who did not wish to join India. Nehru initially sought to negotiate an end to this impasse. However, when the ruler, the Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan, proved resistant to his requests, Nehru authorized the use of force to ensure the state’s integration into India.

Finally, a third difficult case was Junagadh, a princely state in western India. The ruler, the Nawab Muhammad Mahabat Khan Babi III, acceded to Pakistan despite its predominantly Hindu population. Unhappy with his decision, which defied the directive that states located within the new dominion of India should accede to it, India’s leaders sent in troops to reverse the outcome. To legitimize the decision, the government held a referendum in 1948, in which over 90% of the citizenry voted in favor of the accession.

The departure of the British from their Indian colony left a host of unresolved issues, ranging from the traumas of the partition to the ongoing dispute over Kashmir. These consequences still shape geopolitics in the region, and beyond.

Sumit Ganguly has received funding from the Smith Richardson Foundation and the US Department of State.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.