In the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Moscow is a statue of a small mutt, Laika. A lynchpin in the history of space travel and exploration, she may be equal parts hero and victim.

When she was just two or three years old, she did what no human had done before — she orbited Earth aboard Sputnik 2, which launched 65 years ago today on November 3, 1957.

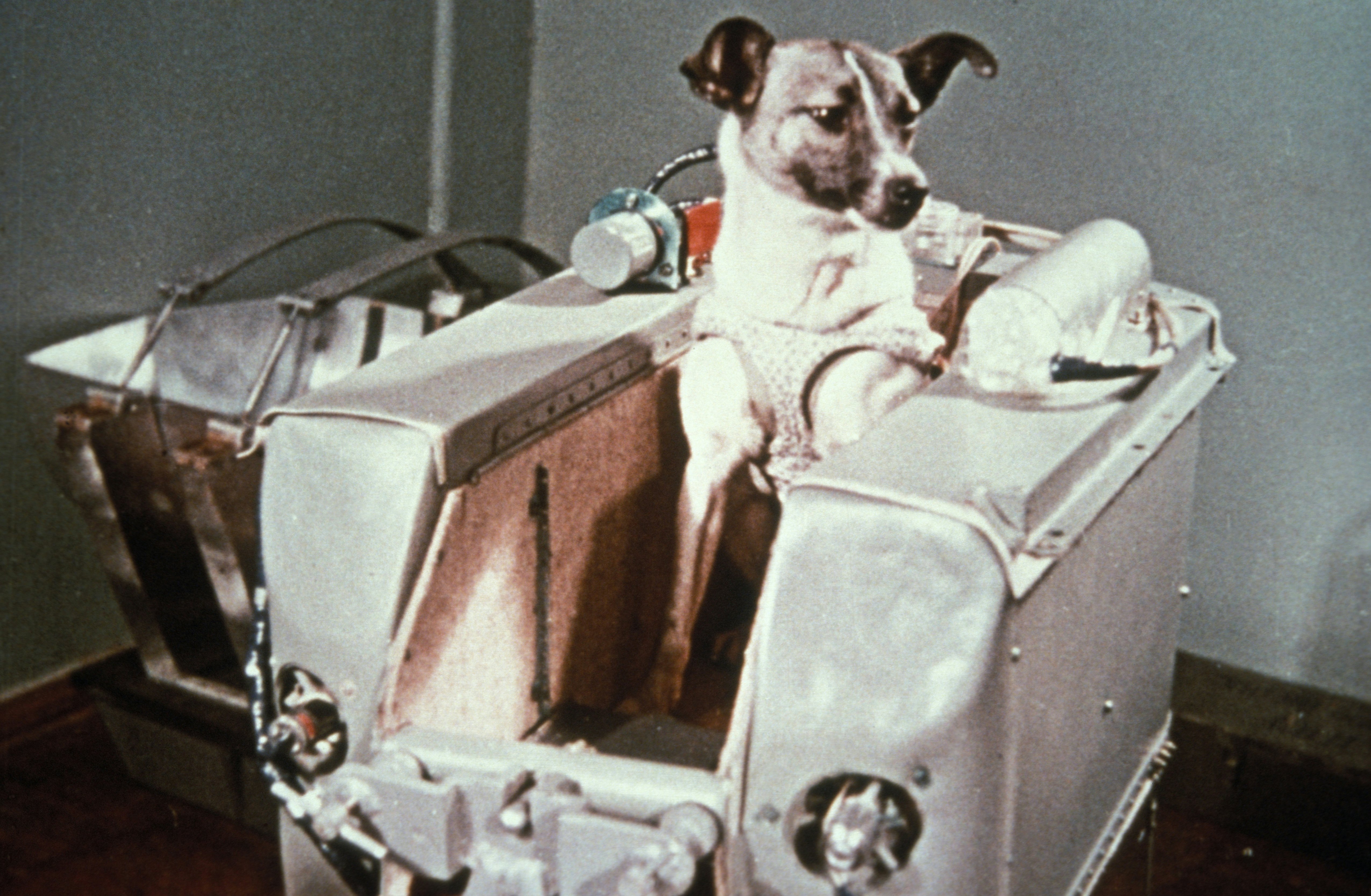

Unlike the Sputnik 1 probe that had flown to space a month earlier, Sputnik 2 had a separate chamber (with a window) to carry a living creature — Laika. The story of Laika’s journey to space is forged in history, but like many Soviet space tales, is not without controversy.

The motivation for sending Laika to space was a noble one. There was little known about the impact of being in space on living creatures — especially humans. Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, explains that animals were sent into space to measure their physiological responses.

“At that point, there was a lot of speculation that a living being would immediately die if it was in weightlessness,” McDowell tells Inverse. “So, a lot of the doctors were very conservative about it.”

“This was sort of just proof of concept that no, nothing magic or weird happens when you spend a few minutes in space in freefall,” he adds.

Early animal experiments in space

As it turns out, Laika was not the first dog that the USSR sent into space, and was far from the first animal sent into space — but all launches before never went into orbit. In 1947, before mammals, the United States sent fruit flies to altitudes greater than 62 miles (the boundary of space recognized by many agencies, known as the Karman line) aboard a V-2 rocket. The fruit flies were returned safely by parachute to study the effects of radiation on DNA.

Later, Albert, a rhesus macaque, was blasted 39 miles into the atmosphere on June 11, 1948. He, unfortunately, died from suffocation before landing. Albert II was the first animal to cross the Karman line when he traveled 83 miles into space aboard a V-2 sounding rocket on June 14, 1949, but died upon landing.

Thereafter, both the Soviets and the US sent dogs and monkeys, respectively, into suborbital space until Laika became the first to enter into orbit. The French even sent a cat, Félicette, into suborbital space. She survived, only to be euthanized shortly thereafter to have her brain examined posthumously. In total, there have been seats for 57 dogs in USSR space flights, though some dogs have flown multiple times. Sputnik 2, the first canine — or live animal — orbital flight, was about in the middle of that. (Fish, frogs, newts, and rats were all also sent to space in this era.)

Laika’s journey

As the Soviets liked to tell the story of Laika’s space journey, it was a smooth ascent, and she survived aboard Sputnik 2 for 7 days, eventually dying painlessly of a lack of oxygen — quickly, in just 15 seconds. As the Americans told it, the tale took on a darker hue; she died quickly when the chamber where she was located overheated, and she burned to death.

As it turns out, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Kurt Caswell, author of Laika’s Window: The Legacy of a Soviet Space Dog and professor of creative writing and literature in the Honors College at Texas Tech University, explained that Laika likely died even before the capsule overheated. He explained that after Laika was sealed in her capsule and it was placed on top of the rocket, there were a number of problems pre-launch that needed to be addressed. So many problems that the rocket sat on the ground for three days prior to launch with Laika sealed inside.

“They finally launch, and three hours later, she's dead. But, she was contained in the capsule for three days and three hours, roughly,” Caswell tells Inverse. “There was this plan to give her these measured feedings where they built this little mechanism that would give her some food once a day or twice a day, but they ultimately decided that was too heavy and cumbersome and it maybe wasn't going to work.”

“So, instead, they just gave her one big plop of this nasty food that they created. She ate all of it right away because she's sitting there on the ground in the capsule doing nothing,” he adds. “And so basically, all that water is then gone. She doesn't have any more water.”

Caswell calculated how much water Laika would have needed to survive seven days in space, which would have been 10 days to warrant for the seven the Soviets claimed she spent living in space and also the three days she spent on the ground.

“It's quite a bit of water, and it definitely was not possible to keep it in that food,” says Caswell. “Plus, you know that if you have to drink water, mammals can't get water from their food.”

Caswell adds that at some point the vets recognized that Laika was already suffering from severe dehydration, so they squirted some water with a syringe into the feeding tray before they launched.

“It makes complete sense that she died quickly. It wasn't really just that the capsule heated up. It was that she likely died of dehydration and she was close to death anyway,” says Caswell. “The heat was just another element that put her over the edge. I found that story much more compelling than Americans vs. Soviets and Christians vs. atheists or something.”

According to Caswell, the Soviet scientists stopped detecting signs of life from Laika after about three hours — no respiration, no heartbeat. However, the Soviet Union didn’t report that she was dead.

“Not only were they reporting it as a victory, but they reported that Laika was alive and well and her time in space was providing necessary information about how to put the first human being into space. Laika’s life is a sacrifice, but it's valuable to science and humankind,” says Caswell.

This would not be the first example of Soviet propaganda under Nikita Kruschev. “Then in the 90s, this Russian researcher scientist was giving a paper at a world space conference and he admits to the world for the first time that actually we knew that Laika was dead early on.”

Life on the streets of Moscow

Laika, like the majority of the dogs used in the Soviet space experiments, was originally a stray dog. Stray dogs were chosen since scientists thought they already had learned to endure challenging circumstances. There were trainings for animal astronauts in the same way as there is training for human astronauts.

“When and if they're successful in that training and they seem to tolerate things like confinement in the small spaces, which were the capsules, and they seem to be undisturbed by the vibration tables that they put them on to simulate what it would be like to ride in a rocket, they would stay in the training, otherwise they would cycle them out,” Caswell says. “And I think most of them were adopted.”

Laika was relatively unlucky in that she was successful in the training and that no one adopted her. Albina, another dog that had been trained with Laika and successfully completed a suborbital mission, was the original preferred candidate. Albina was a white dog and the Soviets preferred dogs that would show up easily on camera. However, she had just had a litter of puppies and was very well-liked by the scientists, so she ultimately became the backup and Laika was the next choice.

Despite what was likely a traumatic experience in heading into space, Laika became a national hero and a symbol. There was even a brand of Soviet cigarettes made in her honor, and the statue in her honor was erected in 1997 in Star City, or the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Moscow. She paved the way for space exploration for humans and, more specifically, Yuri Gagarin, who was the first human to orbit Earth on April 12, 1961.

From a distance, what happened to Laika appears tragic. And while her story is indeed tragic, Caswell adds another layer to it.

“I started thinking about this, not as a kind of lab animal, but as a working dog. We have working dogs that do dangerous things all the time. The Soviet Union was used to working with dogs. We have the Pavlov dog, right?” Caswell says. “The space dogs were working dogs. They were trained to do a job and it was a dangerous job.”

“A number of them died during that process. But, so do dogs that work in wars and dogs that do search and rescue,” Caswell adds. “They'll die in the line of duty. I found that a much more useful way of understanding what was going on there.”