In the short-lived animated comedy Mission Hill, teenage sci-fi dork Kevin shows his two sci-fi dork friends what his cinephile neighbor calls “the greatest science fiction movie ever made.” Kevin is enraptured, but his Armageddon-addled pals are bored and full of angry questions like “What is that stupid black thing?” and “When are we going to fight some aliens?”

Their struggle to wrap their heads around 2001: A Space Odyssey is understandable because the so-called greatest sci-fi ever has long been rendered a punchline by an interminable parade of parodies. Spaceballs, Zoolander, and Everything Everywhere All at Once reference famous scenes, the trailers for The Barbie Movie and The Peanuts Movie satirize its impact, and you could assemble a short recreation from all the times Futurama and The Simpsons mocked it, to name just a few examples. It’s so common to poke fun at its famous soundtrack selection, the opening of Richard Strauss’ “Also sprach Zarathustra,” that when the actual movie plays those booming notes it’s hard to take it seriously.

The whole film, in fact, is difficult to take seriously today, as evidenced by our apparent need to trot out a tedious “I finally watched 2001 and it was soooo boring” essay every year. Lest you think The Atlantic just needed the clicks, Reddit is awash in posts from first-time viewers ranging from “Huh?” to “That was the most overrated piece of artsy-fartsy crap I’ve ever seen.” It’s not that we shouldn’t parody the greats, but 55 years of increasingly stale gags have slowly sucked the life out of 2001, making it easy to forget just what it was.

It’s fair to call 2001 slow, which was the leading complaint among contemporary critics. It’s understandable, if a bit lazy, to call it challenging. You can call it pretentious if you want to take the incurious route. It’s been called everything, really: opaque, hoary, confusing, old-fashioned, only tolerable while stoned.

But that mystique is almost silly when you realize that, for all the talk of 2001 being an impenetrable epic, it’s 40 minutes shorter than The Way of Water or Wakanda Forever. It certainly demands your attention: there is no dialogue for the first 25 and final 23 minutes, and we don’t meet our main character until nearly an hour in. But you’ll soon appreciate the moments that haven’t been picked apart for decades, like the disquieting soundtrack that builds as we approach the mysterious alien monolith at the center of the story.

Maybe 2001 is best read as a statement of intent. Kubrick told Arthur C. Clarke, who co-wrote the screenplay and provided the novelization, that he wanted to make “the proverbial good science fiction movie.” The genre had its classics, like 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still. But in 1968, 2001’s box office rivals included The Astro-Zombies, The Green Slime, and Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. (The Atlantic has yet to look back on Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women.)

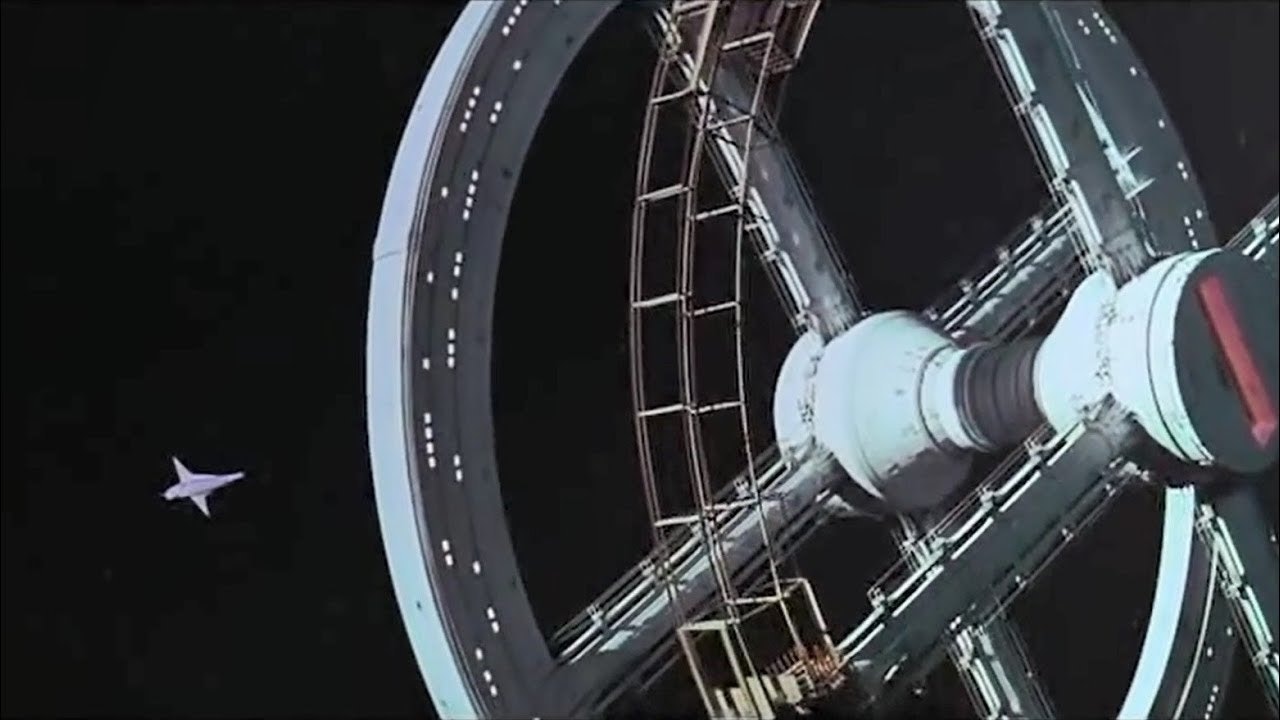

And so while 2001 is famous for its enigmatic space baby, Kubrick was obsessed with getting the technical details of spaceflight right, at least as those details were then understood. Stewardesses combat weightlessness with Velcro socks, space stations generate gravity with centrifugal force, and astronauts communicate with tablet computers and videophones. 2001 understands that space travel can be stately and majestic to viewers and yet, to its participants, it has an element of workaday mundanity. Meticulous attention is paid to the practical technology of an imagined future. It may not be accurate, but it’s credible.

You can even trace the movie’s story through its technology. After a prehistoric introduction, we follow Dr. Heywood Floyd from the Earth to the Moon via a space station stopover. Here, space travel is Howard Johnsons and board meetings. Dr. Floyd is on his way to assess a 4-million-year-old alien monolith, and he’s just as interested in getting his hands on a chicken sandwich. America, on the verge of winning the Space Race upon 2001’s release, was destined to trivialize space.

But then, we cut to Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter, where we’re suddenly dealing with a rogue artificial intelligence and the terror of the endless void. Dave Bowman and Frank Poole’s secret mission to follow the monolith’s broadcast sees them perform tense spacewalks where you hear only their breath and the fragile hiss of the oxygen supply, and suddenly you realize we haven’t mastered anything. Then, the encounter with the alien begins, and it becomes unclear what anything even is.

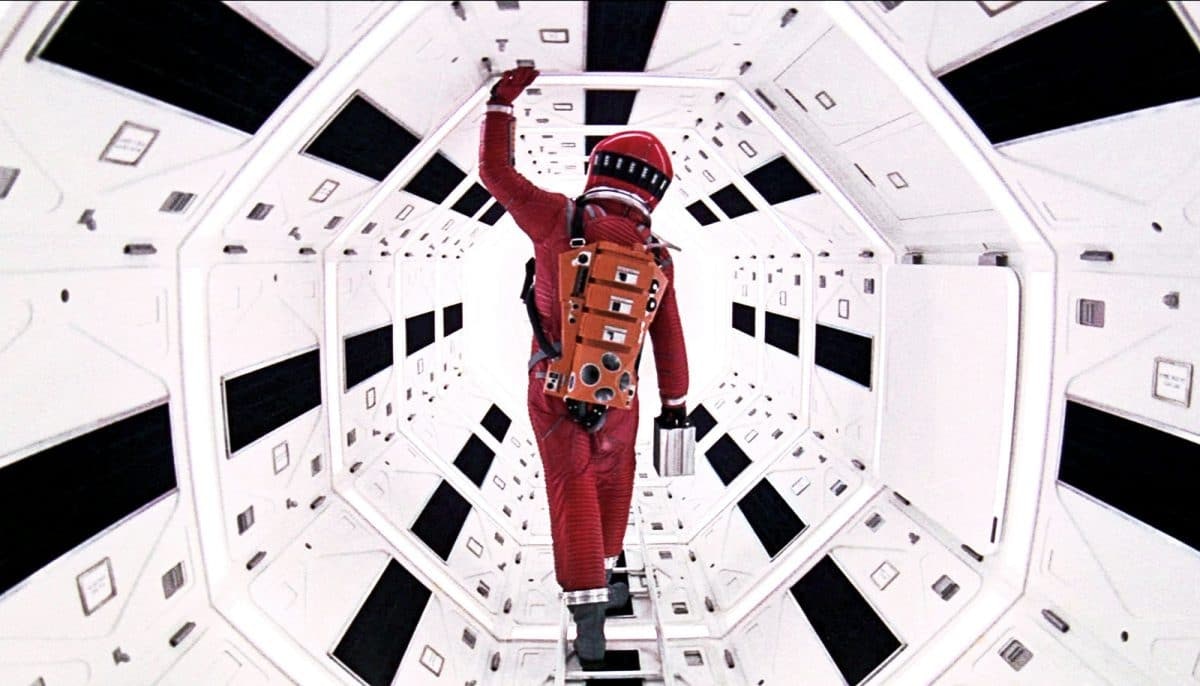

In both storylines, the practical effects remain stunning. Even when you can see the cracks, the tactile details make it all feel more real than modern CGI. This is a production that spent $750,000 on a 38-foot tall rotating set to bring Discovery One to life. It was built for the big screen; complaints about pacing sound silly when you want to gawk at all the details. It’s no wonder 2001’s been cited as an influence by Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, and George Lucas, or that its visual language continues to impact more movies than there’s space to name. It was an attempt to take the future seriously at a time when the genre was rarely taken seriously at all.

“It was important in the ‘60s” is admittedly context, not argument. Asbestos got the job done then too, but that doesn’t mean we should celebrate it. But if you can stop imagining Homer Simpson’s misadventures in half the scenes, 2001 can still sweep you up in its grandeur. It’s a celebration of science as science and the alien as alien, not as ray guns and stuntmen in rubber suits.

None of this means 2001 won’t bore you. It’s such a distinct film that we can only react to it individually, in the same way we react to cilantro and country music. But its influence is, if anything, underappreciated today. If Kubrick and his team hadn’t taken science fiction seriously, who would have?