For many, the Space Shuttle crystallized the American space program in the 1980s. While past the glory days of Apollo — and setting aside the tragic Challenger disaster — the shuttle was the concrete expression of the idea that space would soon be open to everyone, not just heroic Apollo astronauts.

But while the Space Shuttle came alive in the 80s, it was born 50 years ago on January 5, 1972, when President Richard Nixon announced that what NASA would take on as an encore to the Moon missions was not a human mission to Mars or beyond, but a project to make space accessible, and that access safe and affordable.

“The Space Shuttle will give us routine access to space by sharply reducing costs in dollars and preparation time,” Nixon said in his speech announcing the Shuttle Program. “The resulting changes in modes of flight and re-entry will make the ride safer, and less demanding for the passengers, so that men and women with work to do in space can ‘commute’ aloft.”

With our vantage point in the 21st century, we know the space shuttle never quite met the promises Nixon laid out 50 years ago, and the twin tragedies of Challenger and Columbia loom large. The shuttle program saw failures, but it’s a step too far to say the shuttle program was a failure. The reusable (if costly) and certainly roomy shuttle carried dozens of important cargo and satellites to orbit, helped construct the International Space Station, sent the Galileo mission off to Jupiter, and doctored an ailing and aging Hubble Space Telescope. Even if it turned our gaze away from deep space, it gave us a larger frame through which to see both our free-falling astronauts and the Earth itself.

In birth, its life, its tragedies, and even its retirement, the Space Shuttle changed everything about how we go to space.

The deep origins of the Space Shuttle

Nixon did not conjure a space shuttle program out of thin air. It was a concept that had been around for some time, with the military, contractors, and NASA working on the general idea of a reusable “space plane” for years before the concept was presented to the president.

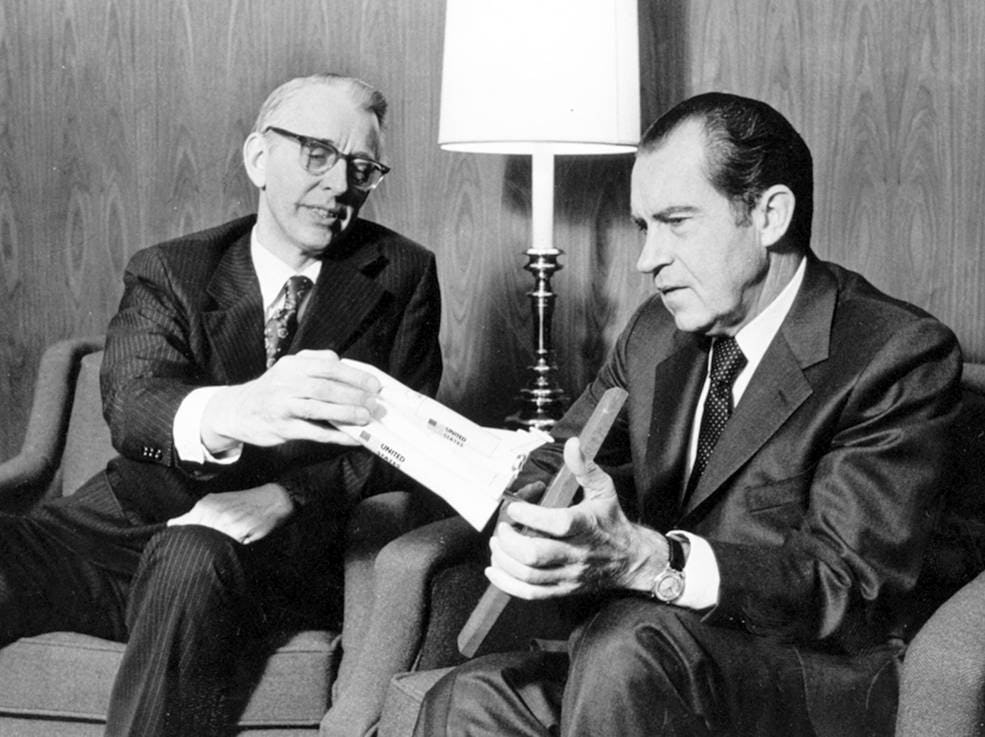

“If you look at images of the [NASA Administrator] James Fletcher talking to Nixon, they've got a fairly well-developed model in their hands,” National Air and Space Museum Space History Curator Jennifer Levasseur tells Inverse. “They're looking at something that looks reasonably close to what we ended up with.”

The concept of a spaceplane was present in popular culture at least as far back as the Buck Rogers comics of the 1930s, she says, while the United States Air Force and Boeing actually tried to build one in the early 1960s, the surprisingly shuttle-like X-20 Dyna-Soar.

“This vehicle would come in and land like an airplane. It had very short stubby wings. It's meant to come in unpowered,” Levasseur says, and though the X-20 was canceled in 1963, the knowledge gleaned from the effort would inform the concept of the space shuttle that eventually received Nixon’s approval.

“We don’t see it splashed on the front pages of newspapers; Apollo is front and center,” Levasseur says, but “NASA and contractors and the military, especially, are working behind the scenes coming up with new concepts.”

Nixon’s shuttle promises

In Levasseur's view, there’s something very, well, Nixonian about the space shuttle.

NASA was already thinking about what to do in human spaceflight after Apollo in 1970 when Nixon announced the program would end after Apollo 17. The year prior, a task force had recommended further adventure with a crewed mission to Mars.

But Nixon rejected the idea, at least for the time being. While he liked astronauts and their achievements, he ultimately viewed NASA as just one more domestic program competing for limited federal dollars, and there was that pesky and expensive war in Southeast Asia to consider.

“By no means should we allow our space program to stagnate. But with the entire future and the entire universe before us — we should not try to do everything at once,” he wrote in March of 1970. “We must also recognize that many critical problems here on this planet make high priority demands on our attention and our resources.”

The space shuttle concept resonated with Nixon. It was a concept to match the president’s rhetoric: a practical vehicle that would make space access routine, focus efforts in space near Earth for the near term and provide a tool for putting anything the government wanted into space — including classified spy satellites.

“Things are defined very loosely by John F. Kennedy’s administration, and they’re defined much more specifically by Nixon,” Levasseur says, a departure in style and intention that’s apparent in Nixon’s announcement of the shuttle program.

“It will revolutionize transportation into near space, by routinizing it,” Nixon said in his announcement of the shuttle program. “This new system will be recovered and used again and again — up to 100 times.” He added that the shuttle would cost significantly less per launch than existing launch vehicles.

NASA and government officials had discussed multiple sizes and configurations for the space shuttle leading up to Nixon’s announcement, including several iterations significantly smaller than the final spacecraft. But the concept that one out was the one described by Fletcher when we followed Nixon to the microphone to fill in the details.

“The Space Shuttle will consist of an aircraft-like orbiter, about the size of a DC-9. It will be capable of carrying into orbit and back again to Earth useful payloads up to 15 ft. in diameter by 60 ft. long, and weighing up to 65,000 lb,” Fletcher said, adding that “The orbiter will be launched by an unmanned booster.”

Note the singular “booster” — it would take more than a month for NASA to settle on using two solid rocket boosters mounted on either side of an external liquid fuel tank. Nixon’s specificity was primarily performance and capacity related, and those parameters would prove to hem NASA in as it embarked on the decades-long shuttle program.

“This is defined in 1972, long before anything’s been built, long before real things have been tested,” Levasseur says, but it commits NASA to deliver on Nixon’s promises. “It really does tie NASA to certain principles of reusability and the economics of it all.”

The successes and tragedies born or boredom

The Space Shuttle could deliver on reusability, but in some ways, it may have led to the program's failures. First flying a decade after Nixon’s announcement in 1981, the shuttle did make spaceflight routine — so much so it may have become problematic.

The shuttles used their large cargo bays to deliver multiple satellites and payloads to space in the early 80s, and in 1983, with STS-7, carried Sally Ride, the first American woman into space.

But “when you get a largely successful period without significant challenges,” Levasseur says, “it breeds complacency.”

Commissions later charged with investigating the loss of the Challenger and Columbia shuttles would note that people within NASA raised warnings about the problems that would prove fatal for both spacecraft. An O-ring failure in one of the solid-rocket boosters was responsible for Challenger’s fiery demise at launch in 1986, while a piece of foam shaken loose from the external fuel tank during launch damaged Columbia’s wing, allowing the heat of re-entry to penetrate the thermal protection system.

“Retrospectively, astronauts knew the problems with the shuttle,” Levasseur says. “It was never really a full-fledged operational vehicle.”

The flaws inherent to the solid rocket boosters that would ultimately doom Challenger were referenced as early as 1972 in documents analyzing the pros and cons of solid and liquid boosters for the nascent shuttle.

Astronauts on the first shuttle flight in 1981 raised the possibility of the loss of any of the thousands of ceramic tiles affixed to the Space Shuttle’s belly like dragon scales to shield it from the heat of re-entry, for instance.

“How could you expect it to perfect over 20,000 tiles every single time for every single mission?” Levasseur says. “That’s what makes the vehicle fundamentally flawed. You can’t possibly have that many components and expect every single one of them to work perfectly every single time.”

But physical complexity can be mitigated by operational awareness, she notes, and it was ultimately institutional failures that led to the shuttle disasters. It was an adherence to schedule, to the ideal of making spaceflight routine, that led to Challenger launching when it shouldn’t have flown.

It was cold the morning of January 28, 1986, around 36 degrees Fahrenheit. The engineers who had built the shuttles solid rocket boosters knew that the rubber O-rings separating each segment of those boosters lost their flexibility below 53 degrees. They were concerned that the seals could fail with disastrous consequences and told NASA so, but their concerns never reached the top decisions makers at NASA.

And those decisions makers, for their part, were focused on making up for delayed flights and fewer shuttles flights than expected. They focused on how launching the first school teacher into space, Christa McAuliffe, would rekindle the public’s fading interest in the shuttle program — assuming they launched on time in front of the television cameras.

“That adherence to that ideal becomes overwhelming,” Levasseur says, “and ends up costing the lives of astronauts.”

The Space Shuttle’s legacy

But NASA learned from both tragedies, and after each one, the shuttle flew again. It was instrumental in building the ISS, and it was the only spacecraft capable of servicing the Hubble Space Telescope — the final flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, in May 2009, was also the final in-situ repair for the orbital telescope.

In many ways, the shuttle proved very true to Nixon’s vision, serving as an orbital truck. It also made space in some sense boring, but that, Levasseur notes, was also an inherent part of that vision.

“This all kind of rings very Nixonian to me,” she says. “It’s not exciting; it’s not sexy.”

But the shuttle still holds a place in the imaginations of people who worked on it or grew up watching the launches. And it imparts a lesson Levasseur says is important to keep in mind as NASA ventures back to the moon, and private space companies move into the space station and deep space exploration business — there’s never really such a thing as routine spaceflight.

“We have to assume space is a natural force that is always going to work against us. That’s why we don’t live there naturally,” she says. “Spaceflight is much different than getting in your car and driving down to the supermarket. It’s never going to be that simple.”