Nintendo began its long legacy of play with paper.

Decades after its founding as a playing card company in 1889, it eventually transitioned to more modern parts: electrical circuits, chipsets, OLEDs. But five years ago, on April 20, 2018, Nintendo pivoted back to its origins with Labo.

Nintendo Labo, the experimental suite of D.I.Y. cardboard Switch peripherals, leveraged the flexibility and power of simple materials combined with the ingenuity of the company’s most creative minds to build something wonderfully weird. It was quintessential Nintendo. It was also doomed to fail.

On the day of its launch, The Guardian predicted “the next few months will determine whether Labo becomes a fondly remembered curiosity, or another of the Switch’s big sellers.”

Expectations were high. Bill Trinen, Vice President of Player and Product Experience at Nintendo of America, posted his pre-launch sentiment in a tweet: “If you have a Switch, you’re going to want Labo.” He followed it up with a prescient hedge: “We shall see.”

About a month after Labo’s launch, Tonight Show host and part-time Nintendo proselytizer Jimmy Fallon wrangled The Roots and Ariana Grande to perform her hit “No Tears Left to Cry” using nothing but Labo-builds as instruments. Nearly ten million people have watched the video. But for most of them, watching was enough. Sales underwhelmed, with just over a million units sold after its first year and never accruing much momentum afterward.

Compare that to Ring Fit Adventure, another mad idea using the Switch’s unique controllers in an untraditional way. The game became a slow-burn blockbuster, selling upwards of 14 million copies since its release in October 2019.

So, what happened?

The problem with Labo

In early 2018, the Switch was barely a year old. After a gangbusters launch year that started with Breath of the Wild and ended with Super Mario Odyssey, Nintendo was heading into its second year with a softer lineup. Ports of Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze and Dark Souls had just been announced when word of “something new” came down.

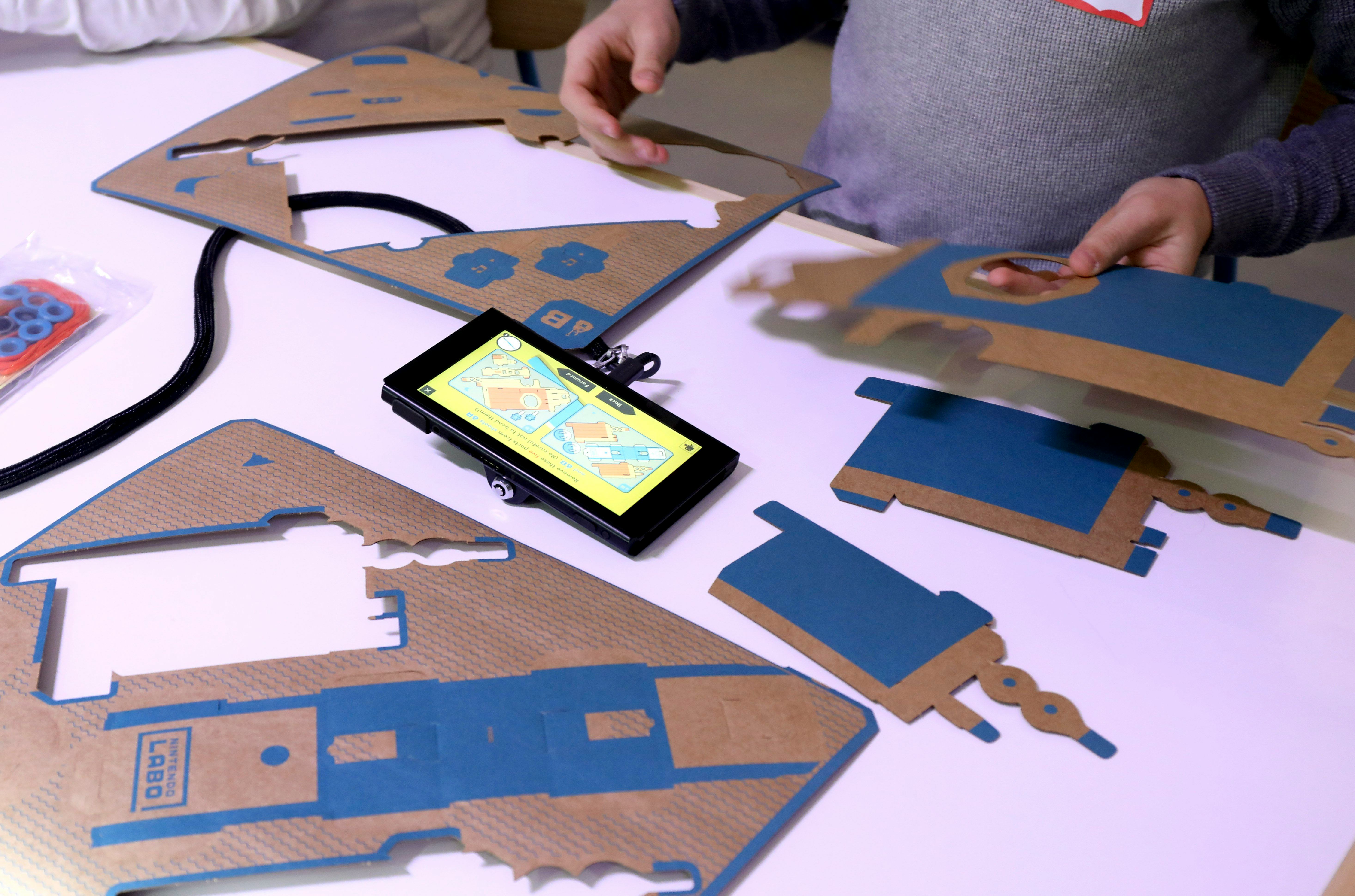

On January 18, Nintendo released a first-look trailer that has since been taken off its official YouTube page. In it, sheets of cardboard travel down a conveyor belt before being stamped and perforated. A young woman’s hands push out the various pieces and clicks them together. They begin to form a piano. Enveloped by a cavernous white room, she kneels before her creation and pushes a key. A note rings out, then a swelling melody that accompanies glimpses of future contraptions: a bird, a camera, a small house.

The production value and storytelling evoke an impending paradigm shift. Labo was not a quirky side project. It was a new platform, impossible without the unique components in Nintendo’s Switch hardware.

But Labo’s release schedule was piecemeal and its naming conventions were confusing. Each set was called a “Kit,” and each do-it-yourself controller was called a “Toy-Con.” The full series was split between four models and three separate release dates.

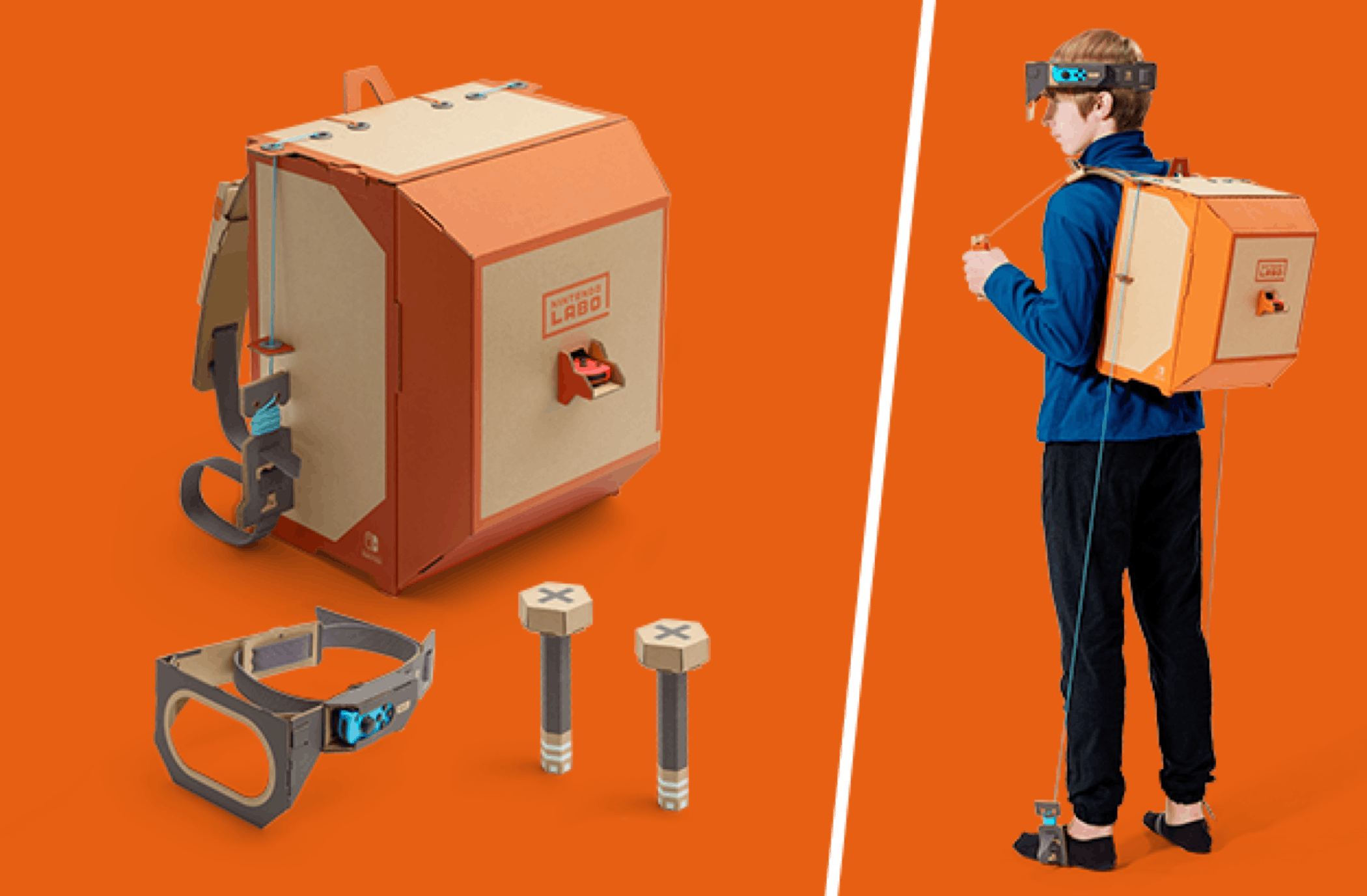

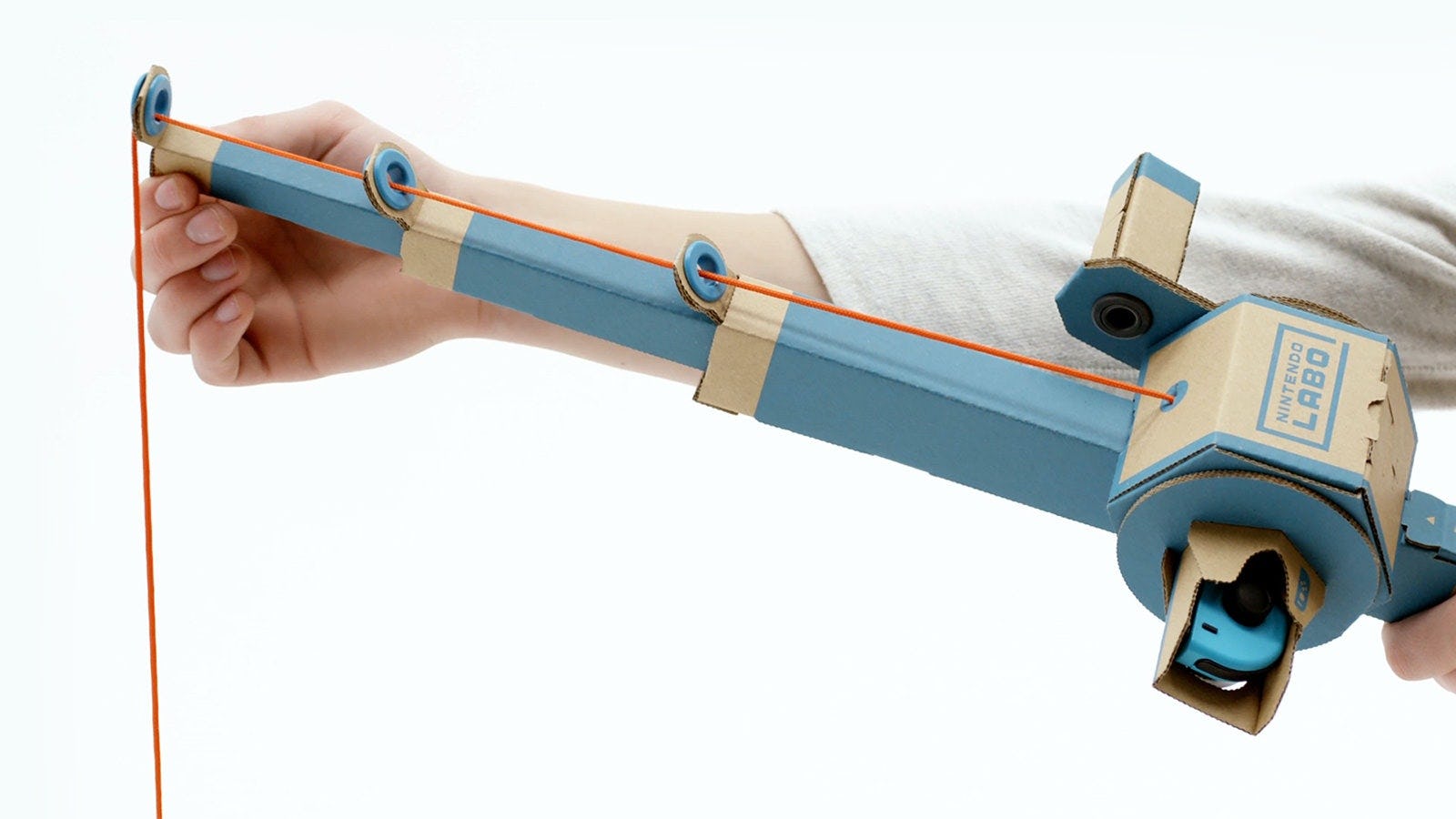

The Variety Kit and Robot Kit came out first, on April 20, 2018. The Vehicle Kit, which includes a a steering wheel, a flying yoke, and a submarine “control station” launched that September. But the final release was Nintendo’s most ambitious. The VR Kit amounted to a pair of cardboard goggles designed to hold the Switch up to your face. The relatively low-res screen makes for a grainy experience, but this was never meant to replace a high-end headset.

These are quick, charming, surprisingly shareable experiences. Here, shoot a watermelon into a hippo’s mouth. Draw some sketches using a 3D pen that looks like an elephant snout. Blast some aliens using a big chunky shotgun with very satisfying pump-action and recoil.

Most people assumed this was a product aimed at kids. Or parents with kids. And I guess it was. But it was also for me: a then-30-something who built his Labo after the wife and kids went to sleep. I’d put on Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage,” clean off my coffee table, and start building.

Of the nearly hundred titles I’ve played on Switch, the three Labo kits I own are all in my top fifteen “most-played.” Building them is playing them. Making these impossible contraptions became a late-night ritual that evoked a feeling I’d feared had left this aging body.

Labo was a big swing at engaging non-traditional game consumers: parents interested in STEM education for their kids; model builders who’d graduated from Lego blocks; VR afficionados. Ultimately, the barriers to entry — and price — were too high for casual dabblers, and the playable content was too light for core customers looking for a meatier experience.

Me, I like to nibble. I’ll always prefer a bite of food I’ve never tasted before to gorging on a 40-ounce steak. So Labo was a wonder. Five years on, it still is. And in this moment of digital storefronts closing and blocking access to entire eras of games, there’s one advantage Labo will always have: You don’t have to download cardboard. The material is purposefully ephemeral: Build them, play with them, draw on them, share them… and, eventually, recycle them.

No new ideas

Of course, it had to be paper.

Perhaps Nintendo’s developers remembered building the paper kits the company made long before it entered the videogame market. In 1974, Nintendo released a series of Paper Models, which swapped out hard plastic in favor of thick paper sheets. With oil prices spiking due to skirmishes in the Middle East, the company was frugal to the point of forcing creativity on its designers.

These Paper Models looked and felt like the marriage of model car kits and paper dolls. Assembling them was messy work, involving scissors and glue. They came in four categories: Vehicles, Buildings, Zoo, or Panorama. You could build a helicopter or a San Francisco cable car. Or a family of lions. Or a tiny Notre Dame cathedral. The Panorama were the most elaborate, with scenes like an Old West frontier town or a bustling airport. Sure, they were somewhat fragile, but the kits were a modest success.

Old ideas sometimes come back into fashion if you wait long enough. In 2018, papercraft was not the hot new thing. But designers were tasked with doing something with these new controllers that could be split off from the device. The implied question was always: What else could we slide these controllers into? What else could the Switch become? And what materials would allow for kids to easily tape together if they mess up, or color onto with their favorite markers, or affix stickers to make their creation their own?

Labo made good on the promise of a modular gaming system. Many Nintendo consoles lay claim to a quirky and fun peripheral with limited use. There’s the original NES and its “robot buddy” R.O.B., the SNES’s Super Scope 6 bazooka, the GameCube microphone used to yell at giant medieval pinballs in Odama, and even one system (3DS) that became a controller for another system (Wii U) in Super Smash Bros. Nintendo’s fondness for non-traditional control schemes and beyond-the-screen objects harkens back to their pre-gaming days as toy cobblers, creating automatic baseball pitchers or extendo-grabbers that were simply fun to use.

Once Tsubasa Sakaguchi, lead director on the Nintendo Labo project, started experimenting with the Switch’s unique Joy-Con, he realized these weren’t really controllers at all.

“At the beginning of the process I didn’t realize it,” he said during an interview published on Nintendo’s official site in Australia, just before the first Kit’s launch. “But the Joy-Con are sensors before they’re controllers.”

By stuffing these bespoke cardboard creations with these sensor-rich devices, a handful of perforated sheets, folded and linked together, can become a fishing rod, motorcycle handlebars, or even a tiny creature’s house. It’s a project that’s only possible with this specific hardware. And Nintendo’s history is filled with what they call “hardware-software integration” — a very unsexy way of saying “We can do things that the competition can’t.”

During the prototyping process, Sakaguchi and his team realized playing with them wasn’t the best part. They had more fun building and understanding how the contraption actually works.

“We wanted to make an experience that helped people see that discovering how things work is fun in-and-of itself and that making things is rewarding,” he said elsewhere in the pre-launch interview. By using cardboard, the building itself became part of the game.

“We realized that using cardboard and having the customer build the projects themselves was the right direction to go in,” Sakaguchi continued. “It took a potential weakness in the project and turned it into a strength.”

Lessons learned

Most of Nintendo’s most successful games are straightforward and intuitive. You press start and go. Here, you open the box, start the software, separate the pieces from a large sheet, and follow the steps… the whole enterprise is a tall order for folks looking for a turtle to jump on.

Perhaps people have become more accustomed to eating pre-packaged meals. My wife loves crab, especially when you have to crack the shells yourself. Personally, I find the whole affair to be too much effort for too little meat. But with Labo, I was enthralled with the mess: The floor covered in perforated cardboard sheets, the multi-step instruction sequence, and the cupboard-filling excess of these bulky contraptions.

Five years later, Nintendo Labo is still a work in progress, one given up on too soon by players and its creators. At least Nintendo has a tendency to return to old concepts. With the inevitable rumors of a Switch successor on the horizon, this writer is crossing his fingers he’ll be using them to fold more interactive cardboard soon.

Cult of Nintendo is an Inverse series focusing on the weird, wild, and wonderful conversations surrounding the most venerable company in video games.